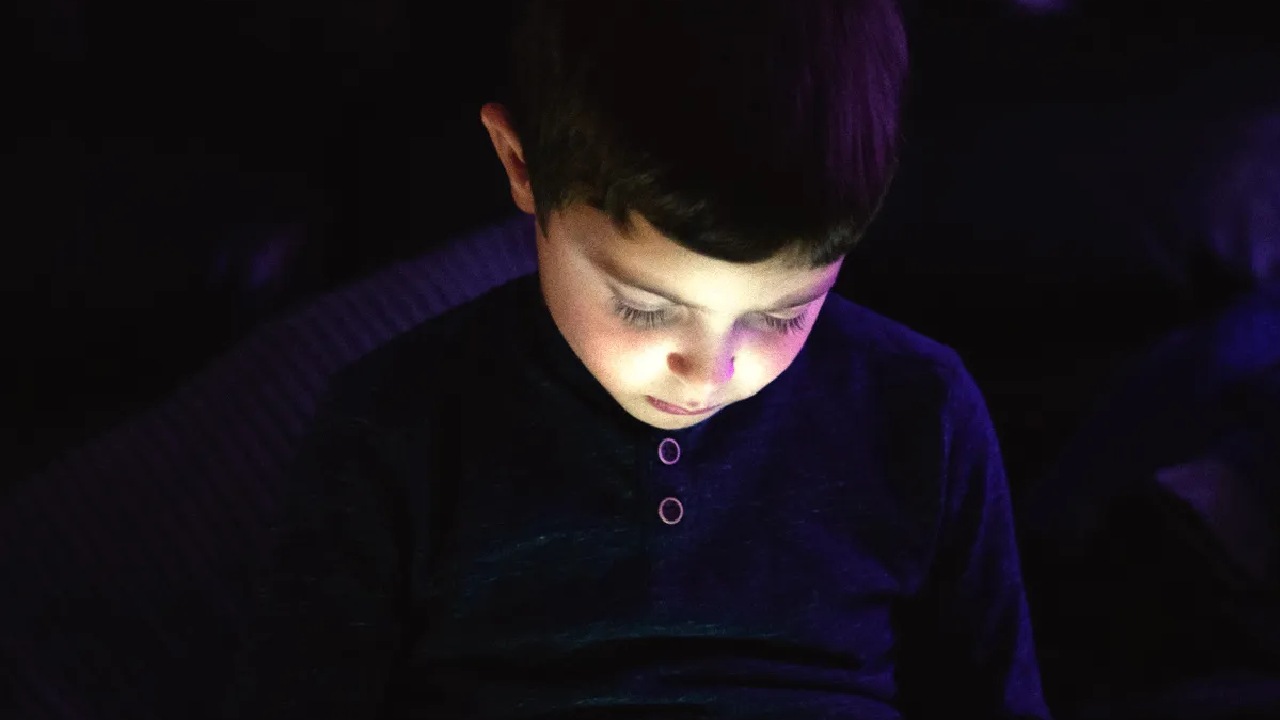

The psychology behind digital dependence

‘My son doesn’t end the game. The game ends him.’ This haunting remark by a parent to a psychologist captures a quiet crisis unfolding inside Indian homes and classrooms. For the first time in human history, childhood is not being eroded by hunger, labour or lack of opportunity, but by perfectly engineered screens. This is not simply a story about excessive screen time or weak parenting. It is about a deeper loss of control — where children no longer decide when to stop because the technology they use is designed to prevent stopping. Those who grew up in the 1990s recall a very different rhythm of entertainment. Games ended when boredom crept in, electricity failed, or parents called children outside. Television followed fixed schedules and free time naturally spilled into outdoor play.

Today’s digital ecosystem has erased such natural endpoints. Games are endless, social media feeds never conclude, and engagement does not pause — it escalates. Children are no longer choosing to stay; they are being held. This shift from voluntary use to psychological capture is one of the most significant behavioural transformations of the 21st century.

What earlier generations used for leisure, today’s children increasingly use for escape, validation and emotional regulation. This is not nostalgia; it is structural reality. Modern digital platforms are engineered systems designed to seize attention, shape habits and monetise time. Their architecture is deliberate, scientifically refined and enormously profitable. Gaming apps and social media platforms rely on behavioural psychology, particularly dopamine-driven reward loops. Unpredictable rewards - much like gambling — keep users chasing the next win, notification or ‘like’, promising satisfaction while never fully delivering it.

Global research paints a sobering picture. Adolescents now spend more hours on screens than on sleep or physical activity. Many continue scrolling or gaming even when they consciously want to stop. This is often dismissed as poor self-control. In reality, it reflects persuasive design working exactly as intended. When a child cannot disengage, the issue is no longer screen time — it is power. The consequences are visible. Health bodies worldwide report rising screen-related behavioural difficulties, especially among adolescents. India, with its vast youth population and rapid digital penetration, faces an urgent challenge. Activities that once built resilience — reading, sport, creative play and unstructured friendships — are steadily pushed aside.

Neurologically, excessive exposure during formative years affects attention, impulse control and decision-making. Parents and teachers report shortened attention spans, irritability, disturbed sleep and an inability to tolerate boredom. Boredom — once essential for imagination — is now treated as a defect to be eliminated instantly. Emotionally, self-worth is increasingly measured through digital validation. Likes replace appreciation; views replace recognition.

Screens can educate and empower when used wisely. What is needed is balance and accountability: firm boundaries at home, schools that prioritise attention and well-being, public-health recognition of digital overexposure, and ethical design standards enforced on technology companies. If earlier generations were players, today’s children risk becoming products. A society that lets algorithms raise its children should not be surprised when human choice begins to fade.

The writer is an educator; views are personal