Why the Hindu new year matters to India

India is not merely a nation defined by geographical boundaries; it is an ancient and living civilisation whose cultural consciousness has evolved over thousands of years. One of the most profound expressions of any civilisation lies in how it perceives, measures, and celebrates time. Timekeeping is not only a technical or administrative exercise but also a reflection of a society’s philosophy, spirituality, agricultural wisdom, and relationship with nature. In modern India, however, there is a growing tendency to celebrate the English New Year on December 31, with great enthusiasm, even though this date has little connection with India’s civilisational ethos, seasonal rhythms, or cultural traditions.

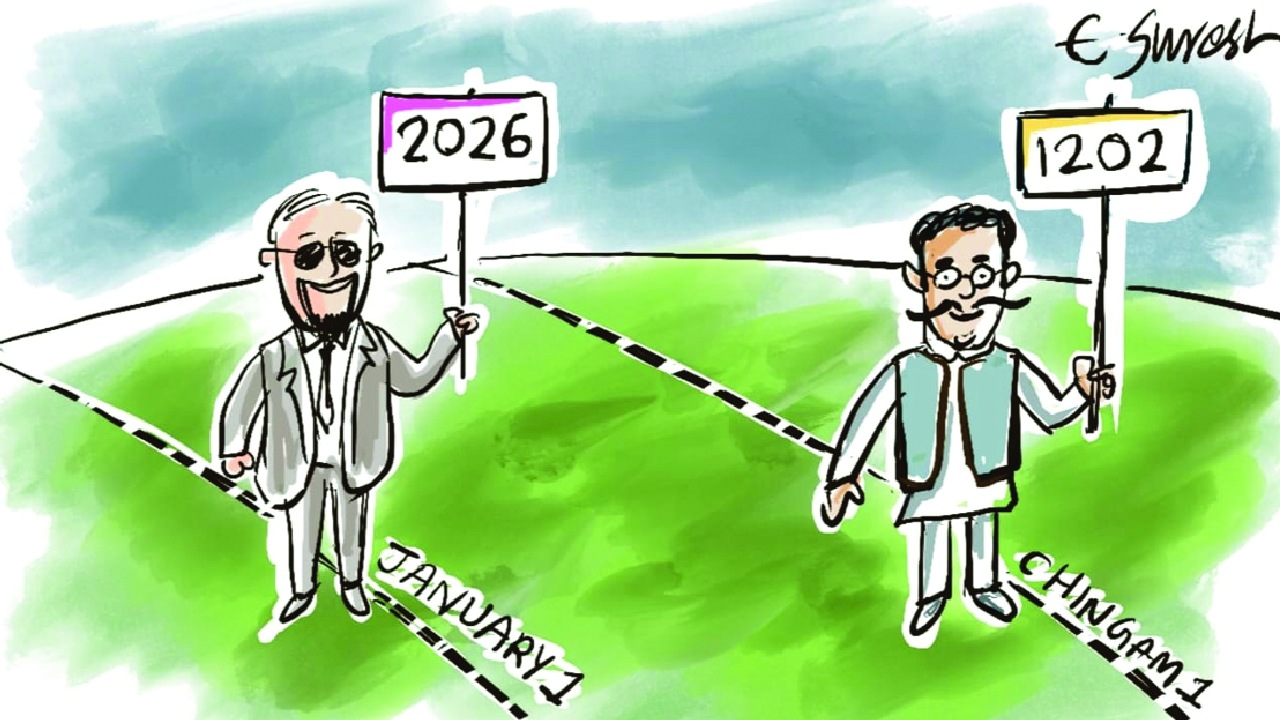

The English New Year is based on the Gregorian calendar, which was introduced in Europe in the sixteenth century and later imposed across much of the world during the colonial era. India adopted this calendar primarily for administrative convenience under British rule, not as a result of cultural acceptance or civilisational continuity. While the Gregorian calendar continues to serve a practical role in global coordination today, its elevation as the primary marker of celebration and renewal in Indian society reflects a deeper legacy of colonial influence that still shapes our social behaviour and mindset.

It is important to recognise that the date of January 1, does not signify any natural, agricultural, or spiritual transition in the Indian subcontinent. It falls in the middle of winter, when nature is largely dormant and agricultural activity is limited. The celebration of this date is largely driven by modern consumer culture, entertainment industries, and social imitation rather than by any intrinsic cultural meaning. Over time, the celebration has increasingly taken the form of late-night parties, noise, and excess, which stand in contrast to India’s traditional values of balance, reflection, and harmony.

In contrast, the Hindu system of timekeeping is deeply scientific, ecological, and spiritually aligned. Indian calendars are based on precise astronomical observations of the movement of the Sun, Moon, and Earth. Systems such as Vikram Samvat, Shaka Samvat, Kali Samvat, and various regional calendars demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of cosmic cycles that predates modern astronomy by centuries. These calendars were not created arbitrarily but were designed to align human life with natural and cosmic rhythms.

Across most of India, the Hindu New Year begins around March or April, coinciding with the arrival of spring. This period marks the end of harsh winter conditions and the beginning of renewal in nature. Trees blossom, crops are harvested, daylight increases, and the environment visibly rejuvenates. This natural transition makes the Hindu New Year a logical and meaningful point for beginning a new cycle, reflecting the Indian worldview that human life should remain in harmony with nature rather than detached from it.

The celebration of the Hindu New Year takes diverse regional forms across the country, reflecting India’s unity in diversity. Festivals such as Gudi Padwa, Ugadi, Navreh, Cheti Chand, Baisakhi, Pohela Boishakh, Puthandu, and Vishu may differ in rituals, cuisine, and local customs, but they share a common philosophical foundation. Each emphasises gratitude, hope, renewal, and collective well-being. Families gather, elders bless the younger generation, prayers are offered, and charity is encouraged, reinforcing social bonds and moral values.

In Hindu tradition, time is regarded as sacred and cyclical rather than linear and disposable. The concept of ‘Kala’ is deeply embedded in Indian philosophy, where every cycle of time presents an opportunity for self-reflection, righteous conduct, and spiritual growth. The Hindu New Year is not merely a change of date; it is an invitation to introspect on one’s actions, renew ethical commitments, and realign life with the principles of dharma. Such an approach nurtures both individual responsibility and collective harmony.

Unfortunately, as Indian society becomes increasingly influenced by Western cultural symbols, there is a visible erosion of awareness about indigenous traditions. The widespread prominence of December 31, celebrations, particularly in urban areas, has overshadowed the cultural significance of the Hindu New Year. This shift does not represent progress or modernisation but rather a gradual detachment from cultural roots. True modernity lies in the ability to engage with the world while remaining grounded in one’s own heritage.

Several nations with ancient civilisations have demonstrated that it is possible to preserve traditional calendars alongside global systems. Countries such as China, Israel, Iran, and Thailand continue to celebrate their traditional New Years with pride and official recognition, without compromising their economic or technological progress. These societies understand that cultural confidence strengthens national identity and social cohesion. India, with its far older and richer civilisational heritage, should display similar confidence in honouring its own traditions.

It is also significant that India already possesses an officially recognised national calendar, the Shaka Samvat, which is used alongside the Gregorian calendar in government documents and communications. However, this recognition remains largely symbolic, as public awareness and social participation in its observance are limited. Bridging this gap requires conscious efforts through education, cultural initiatives, and public engagement so that traditional timekeeping becomes a lived reality rather than a mere constitutional reference.

Advocating the Hindu New Year does not imply rejection of the Gregorian calendar or hostility towards global practices. India has always been inclusive and pluralistic in spirit, accommodating diverse beliefs and traditions. The objective is not exclusion but balance, not imposition but restoration. Indigenous traditions should not be marginalised in their own land, especially when they offer profound ecological wisdom, ethical guidance, and cultural continuity.

Public institutions and leadership play a vital role in preserving and promoting cultural heritage. Legislative bodies, educational institutions, and cultural organisations can lead by example by acknowledging the Hindu New Year through official messages, cultural programmes, and public discourse. Such initiatives reinforce cultural self-respect and inspire younger generations to take pride in their heritage.

As India moves forward as a confident and self-reliant nation, it must ensure that progress is rooted in cultural consciousness rather than cultural amnesia. The Hindu New Year represents harmony with nature, respect for cosmic order, spiritual renewal, and social unity. Reclaiming its rightful place in public life is not a step backwards but a reaffirmation of India’s timeless civilisational wisdom. Celebrating our own New Year alongside global calendars reflects a mature, confident society that honours its past while shaping its future with clarity and pride.