National Voters’ Day: When democracy becomes a movement

India marks its 16th National Voters’ Day today — a celebration second only to general elections in our democratic calendar. Across the nation, millions of citizens will receive their voter identity cards at nearly one million booth-level functions, with a significant proportion being young people who have just turned eighteen. Few know that this transformative initiative emerged from an unscripted moment at a civil society gathering in Bhubaneswar in late September 2010, when a young participant stood up and observed: “Turning eighteen deserves celebration. We should dedicate at least one day annually to honour this milestone of democratic citizenship.” The idea resonated instantly with me, and National Voters’ Day was born from that simple yet profound suggestion.

We did not need any government approval, as it was entirely an Election Commission activity. Yet, by way of information and courtesy, I addressed a letter to the Cabinet Secretary outlining our intention to observe January 25, as NVD, requesting administrative support from ministries and state governments. With barely a week remaining before the inaugural event, his phone call almost made me miss my heartbeat. He said, “Quraishi, your proposal is coming up before the Union Cabinet today.” Proposal? But I had almost implemented it!

Then he proceeded to ask answers to two critical questions: Would we seek declaration of a national holiday? What was our budget requirement?

Our responses rescued the initiative from potential bureaucratic collapse: no holiday required, no financial allocation needed. The Cabinet Secretary’s astonishment was palpable — organising eight lakh functions without budgetary demands represented an administrative rarity he had never encountered in his distinguished career. The solution was elegant in its simplicity: we transformed routine voter registration activities conducted year-round into a coordinated national event, utilising existing allocations rather than seeking additional resources.

President Pratibha Patil inaugurated the first NVD on January 25, 2011, before thirty Chief Election Commissioners from across the globe, all equally fascinated by this ingenuity — a massive project with zero additional budget. The concept’s appeal transcended borders — Pakistan, Bhutan and South Korea, among others, subsequently instituted their own versions of National Voters’ Day, testament to the universal resonance of celebrating democratic participation.

The impact became measurable remarkably quickly. By the 2019 election, following just nine observances, voter turnout reached an unprecedented 67.1 per cent, up from 58 per cent in 2009. This represented nearly 190 million additional voters — equivalent to combining the entire populations of South Africa, Italy and South Korea, or multiplying Canada or Australia six times over, or eighteen Portugals. These were not just numbers; they represented a fundamental shift in how Indians viewed their democratic responsibilities.

NVD soon became the flagship of another Election Commission innovation: the Systematic Voters’ Education for Electoral Participation programme (SVEEP). This too encountered initial resistance, with sceptics both within and outside the organisation questioning whether voter education fell within the Commission’s constitutional mandate. I believed it did, fundamentally and urgently. Persistently low turnout had plagued our elections for decades, undermining the legitimacy of elected representatives and fuelling debates about our First-Past-The-Post system. Demands for compulsory voting gained traction among political leaders. In this context, voter education was not optional - it was imperative, and the Election Commission was its natural champion.

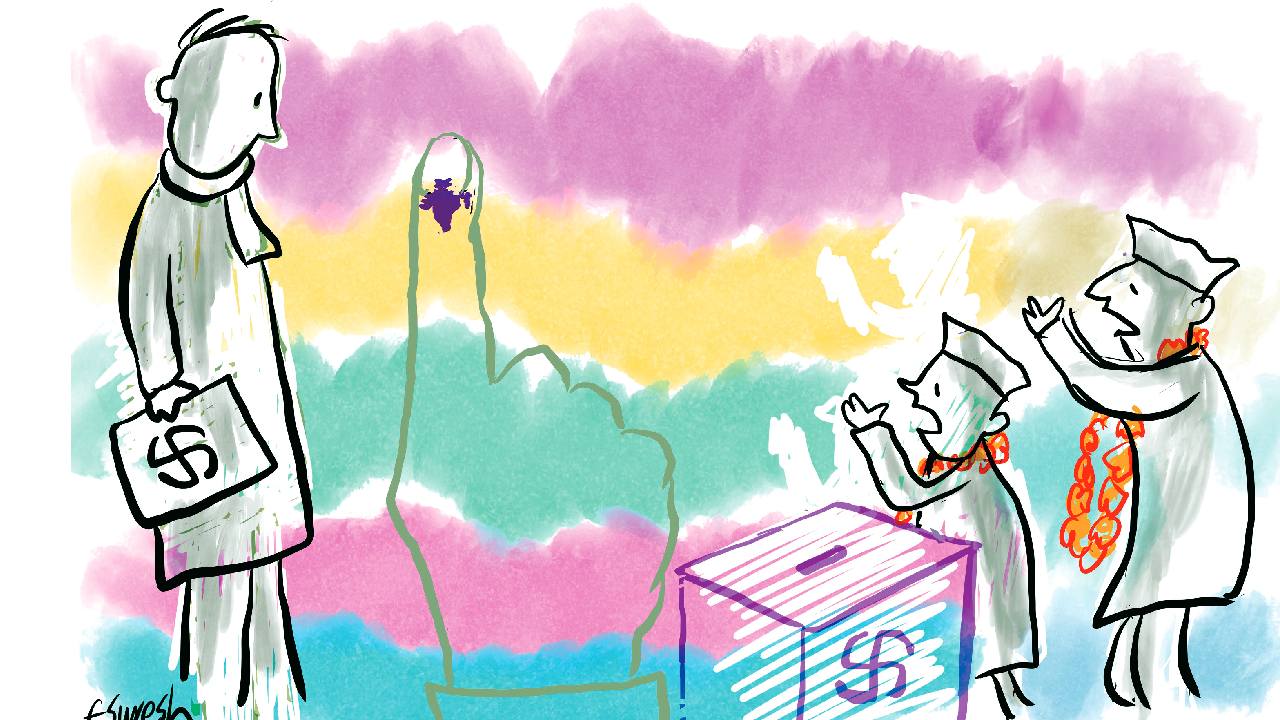

The challenge was particularly acute among educated urban professionals who not only abstained but flaunted their non-participation as a mark of sophistication. Non-voting had become a perverse status symbol. We needed to reverse this perception entirely, transforming electoral disengagement from a badge of intellectual superiority into a source of genuine embarrassment. A 2010 campaign during the Delhi Assembly elections achieved exactly this breakthrough, employing humour to lampoon non-voters with “Pappu doesn’t vote, ahaa” - a parody of a popular Bollywood song. The response was remarkable. Those who had previously bragged about never voting suddenly felt compelled to prove they were not “Pappus,” proudly displaying their inked fingers as evidence of civic participation.

Strategic elements included enlisting brand ambassadors led by former President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, whose moral authority resonated across generations. The youth, hitherto indifferent or even contemptuous of electoral politics, began leading from the front. We appointed 25,000 campus ambassadors across universities and colleges, creating a network of peer influencers. Schoolchildren became enthusiastic watchdogs of voter participation, coaxing their apathetic parents to fulfil their democratic duty. The intergenerational dimension added particular power to the movement.

The results speak volumes: every election since 2010 has recorded historic turnout levels. The 2014 election shattered a six-decade record at 66.4 per cent; 2019 surpassed even that milestone. Several states exceeded 80 per cent participation - figures that would be remarkable in any democracy. Both 2019 and 2024 witnessed more women voting than men for the first time in Indian electoral history - a genuine participation revolution that fundamentally altered the gender dynamics of Indian democracy.

The inked finger evolved from a mere administrative mark into a powerful symbol of civic pride and democratic identity. Reports emerged of restaurants offering discounts to voters, barbers providing complimentary services, and bridegrooms travelling “from marriage mandap to polling mandap” to exercise their franchise before their weddings. Citizens who had once bragged about non-voting now displayed their inked fingers with pride. What began as targeted institutional innovation catalysed behavioural transformation at an unprecedented scale, touching every corner of our vast nation.

Yet NVD’s deeper significance lies in fundamentally reconceptualising democratic citizenship. For decades, we treated voters as passive recipients of political messaging, subjects to be mobilised during election season rather than empowered citizens central to democratic governance. NVD inverted this relationship decisively. By celebrating democratic coming-of-age as a milestone worthy of national recognition, we signalled that voters - not politicians, not parties, not even institutions - constitute democracy’s true sovereigns. The voter moved from the periphery to the centre of our democratic imagination.

The participation surge carries profound implications beyond mere statistics. When turnout climbs from 58 to 67 per cent within a decade, when women voters outnumber men, when urban apathy transforms into enthusiastic civic engagement, we witness democracy deepening in real time. Representation becomes more authentic, more reflective of our diverse polity. The social contract between citizens and the state renews itself with each election, strengthened by broader participation and deeper engagement.

The Election Commission has continued evolving the initiative, recently organising grand Voter Fests attracting lakhs of citizens to participate in diverse democratic celebrations. State icons join these events, and election commissions from countries across continents share best practices, creating a global community of practice around democratic participation.

Challenges undoubtedly remain as we look ahead. Can this momentum sustain itself as the novelty fades? Will digitally native generations maintain commitment to the physical act of voting when so much of their lives occurs in virtual spaces? How do we ensure that the quality of participation matches quantity? As Indian democracy matures, NVD must evolve beyond celebration towards deeper introspection - becoming not merely an enrolment drive but an occasion for examining the quality of democratic participation, the depth of civic engagement, the inclusivity of our processes, and the responsiveness of our institutions to citizen aspirations.

Sixteen years on, National Voters’ Day demonstrates conclusively that democracy is not simply a system we inherit from our constitutional founders - it is a living culture we must actively cultivate, nurture, and renew with each generation, one young voter at a time.

Happy National Voters’ Day 2026!

The writer is former Chief Election Commissioner of India and Chancellor Emeritus, IILM University. His books include ‘An Undocumented Wonder: The Making of the Great Indian Election’ and ‘Democracy’s Heartland: Inside the Battle for Power in South Asia’; views are personal