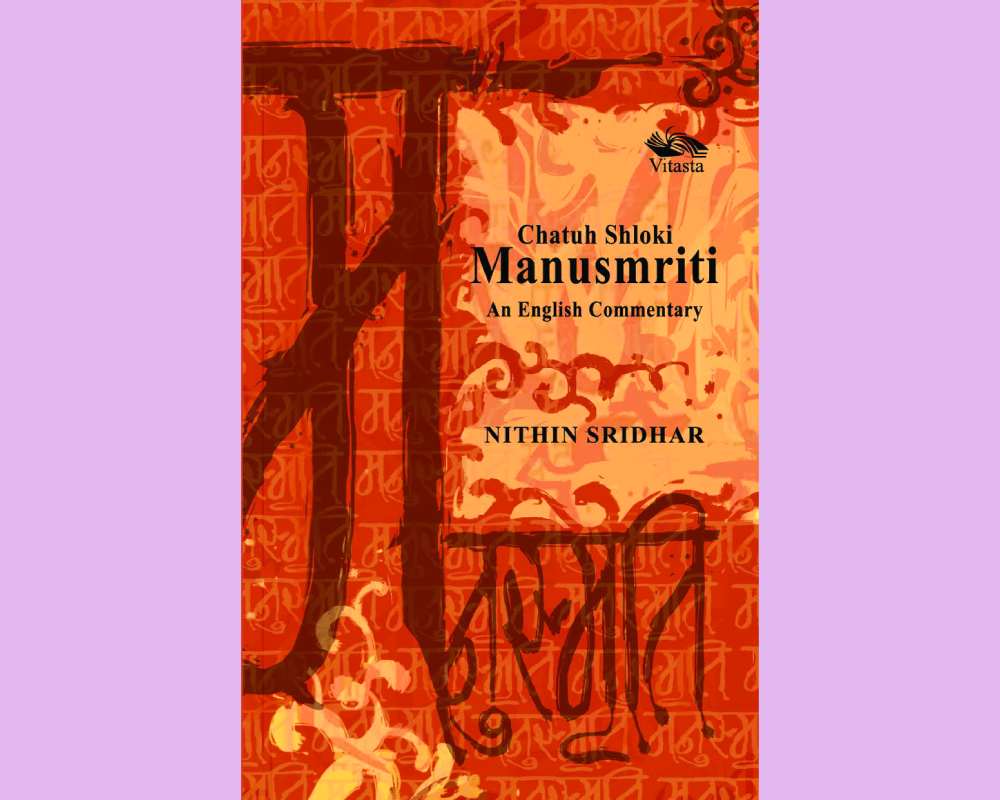

Decoding Manusmriti: A Dharmic Commentary for the Modern Reader

"Just as a tiny seed contains within it the essence of an entire tree, a few luminous verses can reveal the heart of a vast sastra." It is with this insight that Nithin Sridhar approaches the Manusmriti in his Chatuh Shloki Manusmriti.

In an age where ancient Hindu scriptures are frequently misinterpreted or selectively quoted, Nithin Sridhar's latest book Chatuh Shloki Manusmriti (Vitasta Publishing, 2015, New Delhi) emerges as a thoughtful and timely intervention. Rather than offering an exhaustive commentary on the Manusmriti, Sridhar focuses on four verses, using them as a doorway to decode the broader worldview, intent, and dharmic architecture of this much-misunderstood text.

One of the book's core strengths lies in its clarification of what the Manusmriti is and what it is not. While rejecting the common framing of the text as a rigid legal code or proto-constitution, Sridhar repositions it as a pramana-sastra, a text that offers authoritative insight into karma (action) and karmaphala (its fruits). Rather than dictating behaviour, it aims to guide individuals towards self-cultivation and social harmony. In doing so, Sridhar revives the traditional understanding of Smrti texts as eternal, living documents, shaped across generations through abridgements, commentaries, and reinterpretations.

A particularly illuminating section of the book is Sridhar's explanation of dharma. Instead of confining it to legal or moral definitions, he engages with the term through an expansive lens informed by classical sources such as the Mahanarayana Upanishad, Mahabharata, Vaisesika Sutra, and Parasara Smrti.

Dharma, he argues, cannot be reduced to simplistic English terms like 'duty', 'law', 'ethics', or 'morality'. It is that which upholds, nurtures, and harmonises both the cosmos and the individual. Dharma is thus not rigid but adaptive, intended to achieve both abhyudaya (material well-being) and nihsreyasa (spiritual liberation). What further distinguishes this commentary is its treatment of sastra as a rational and disciplined framework. Sridhar emphasises that sastra is not blind rule but a guide for thoughtful living, calibrated to suit context, time (kala), place (desa), and person (patra). While not "scientific" in the modern empirical sense, sastra is rooted in reason, observation, and cumulative wisdom. This aspect is evident in the author's observation: "Sastra provides knowledge about how to act and live life such that one's actions are in harmony with the universe. Dharma is that which upholds the universe, and karma in accordance with dharma sustains it." — Chatuh Shloki Manusmriti

This passage brings out sastra's role as a normative guide for human conduct. Sridhars commentary follows the traditional bhasya style of interpretation deeply rooted in classical Indian exegesis, yet he does not shy away from contemporary debates.

Although many modern scholars view the Manusmriti as a composite text that evolved over time, Sridhar foregrounds the traditional understanding of its transmission through established recensions, especially the Bhrigu recension, which has been preserved within the broader manuscript tradition and is available to us as the extant text of the Manusmriti. His comparisons with texts like the Kamasastra help readers contextualise this process and free the Manusmriti from rigid historicism. What Sridhar accomplishes most effectively is a quiet but firm methodological correction to both popular distortions and Indological oversimplifications. Whereas scholars such as Patrick Olivelle approach the Manusmriti through a historical-critical framework that foregrounds stratification and redaction, Sridhar reads it as a living sastra whose authority is not undermined by its long and layered transmission. This contrast is crucial: instead of treating textual development as evidence of inconsistency, Sridhar foregrounds the traditional understanding of transmission through well-established recensions, particularly the Bhrigu recension preserved within the manuscript tradition.

He presents this not as a debate about single authorship but as characteristic of the Dharmasastra corpus, where continuity is maintained through parampara, shared thematic structures, and an inherited intellectual lineage rather than the modern expectation of an identifiable author. In doing so, he restores interpretive autonomy to the dharmic knowledge system, placing tradition rather than external academic categories at the centre of understanding. Finally, Chatuh Shloki Manusmriti is not just a commentary; it is a gentle yet firm attempt to restore intellectual honesty and civilisational depth to a much-maligned text. By combining scriptural insight, traditional commentary, and reflective clarity, Nithin Sridhar offers readers-especially modern seekers — a meaningful framework to understand the Manusmriti in its proper spirit. For anyone interested in Indian philosophy, Hindu jurisprudence, or dharmic ethics, this book is essential reading.

(The writer is an author and columnist); views are personal