Contrary to popular belief, dividing society has not always been the norm of State policy; even the British united India in more ways than one

Divide and rule” would be a ready excuse for many an Indian to use where he/she cannot explain the cause of say, a Hindu-Muslim riot, or any other such dispute or conflict. Tactically, an official or a local politician using this excuse is understandable, but for a person who knows modern Indian history, routinely dishing out this excuse is unpardonable.

The East India Company began its political career in present-day Madras (now Chennai), a settlement that they founded for the purpose. Its core officers and soldiers lived in their fort. The first Governor was Andrew Cogan. The Company’s business activities then spread to Bombay, which had been given by the King of Portugal to his son-in-law, England’s King Charles II, who gave the islands to the Company a gifted lease of £10 per annum. The first effective first Governor of the city was Gerald Aungier, who developed the fishing village into a township and established its headquarters at Fort George (not St. George, which was the East India Company’s name for its Madras settlement). All this happened in the late 1660s.

The East India Company’s first commercial establishment was opened in 1644, although it was developed into a full-fledged settlement with the building of Fort William and the acquisition of Govindpur, Kolikata, and Sutanoti from the Nawab of Bengal. However, the founding of Calcutta city is dated to 1690, by the legendary Job Charnock. But the city had to wait until 1700 for its first Governor when Sir Charles Eyre was installed. The three establishments were known as Presidencies, quite independent from one another, and directly reported to the Company’s London headquarters.

There was no postal service in India in those days although ships came and went to and from these three ports. There was no particular complaint about this arrangement. Nevertheless, the Westminster parliament—not the East India Company’s Court of Directors—chose to pass the Regulating Act of 1773, whereby the Governors of Bombay and Madras were asked to begin reporting to Fort William at Calcutta. The Governor at Calcutta then was designated the Governor-General in India. This was evidence enough that the English government did not have “divide and rule” in its mind. Had it been otherwise, London would have allowed the three Presidencies to grow independent of one another and flower as three separate countries, and not bunch them together as one administrative entity.

One must assume that it was difficult for people in London in the 17th and 18th centuries to appreciate the significance of communal rivalry prevalent in India. But then how would several other measures, encouraging rather than discouraging steps that would ultimately lead to an integrating India, be explained?

The Indian Civil Services (ICS), which later birthed the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) that runs independent India’s administration and other senior services need not have been all-India institutions; they could have been different in the different Presidencies. For instance, the civil administrative services in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) and Burma were distinct and did not have similarities with India.

If Macaulay’s formula of introducing English education in the country had not been proposed and then implemented, an Oriya might have found it difficult to communicate with his Bihari neighbour. What if the English rulers had chosen to structure the armed forces Presidency-wise, rather than under a single umbrella?

A common currency is a boon but having to change one’s currency notes when crossing over from one Presidency to another, certainly isn’t. Had such a measure not been implemented by the British, would the free flow of trade and commerce in the entire country have even been conceivable? Just imagine what the level of India’s contact is with Pakistan on one hand and Bangladesh, on another. Myanmar, then called Burma, was a province of British India until 1937. What is our level of understanding and interaction with that country today, even though it is our next-door neighbour?

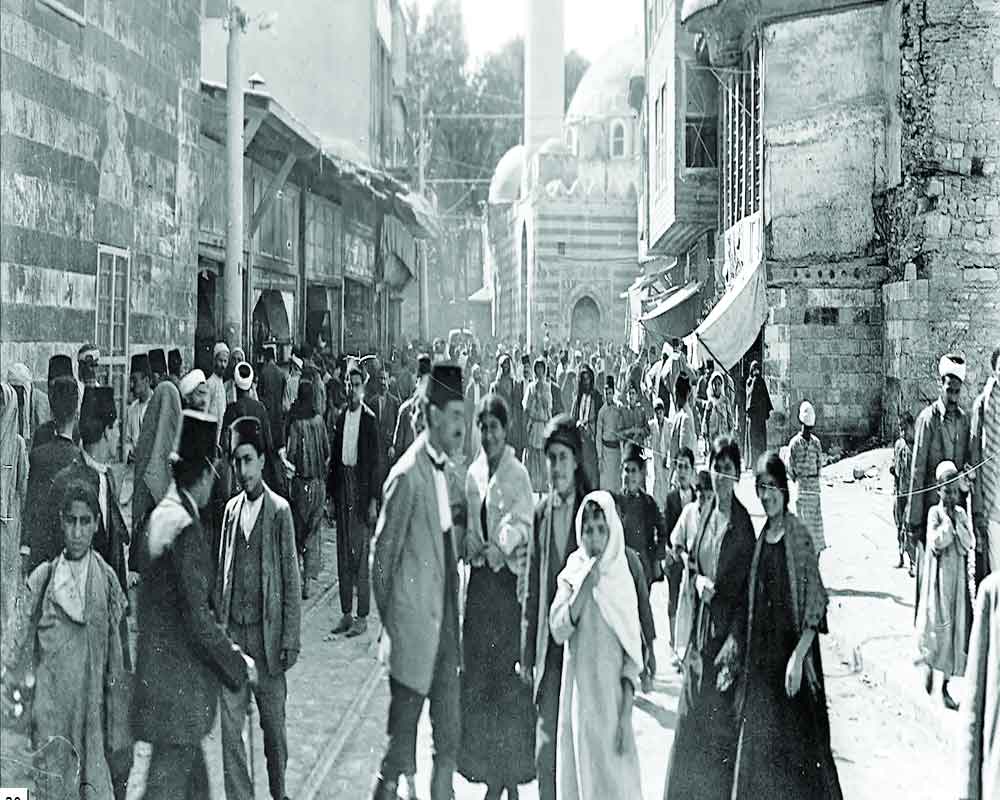

Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who founded Pakistan, was candid enough to say that Pakistan was born the day the first Hindu was converted. That happened early in the 8th century AD. Since then, India was invaded continually until 1760 AD. Only during the fifty-year reign of Emperor Akbar and his successors Emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan was there cordiality between communities. Otherwise, most of the time, there was at least an undercurrent of discord, especially due to the imposition of jaziya on the one hand and temple desecration on the other; both measures were the hallmark of the rule of Aurangzeb. By the end of his reign, the Rajputs, Sikhs, Jats, and finally the Marathas were in open revolt. Aurangzeb admitted his failure in his letters to his sons saying “I come and go as a stranger. I know not who I am. I lacked leadership and my duty in protecting the people”. Aurangzeb also expressed the fear that his officials and troops would be ill-treated (by his enemies) after his death.

All this made sure that the two communities could not see eye to eye again. Even the Partition could not fully heal the wounds. Why, therefore, the insistence on laying blame only upon the British for “divide and rule?”

(The writer is a well-known columnist, an author and a former member of the Rajya Sabha. The views expressed are personal.)