Concomitant institutional reforms with a focus on empowered city governments having the capabilities to implement strategies that are feasible are urgently needed

Rapid urbanisation in India has not met adequate planning, governance and infrastructure development. The impact of the pandemic has exposed the shortcomings of our cities in addressing urban densification and the inadequacies of basic services, including power, transportation and sanitation. Given the predominance of informal production and labour relations, a cessation of major economic activities in the cities during the lockdown and beyond has had an adverse socio-economic impact, especially on the urban poor. Nevertheless, the outbreak has provided a window of opportunity to rethink the glaring gaps in our cities and the policy rhetoric. Against the backdrop of the pandemic, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman prioritised urban development in the Union Budget 2021-22, which is evident from the nine per cent increase in financial allocation from Rs 50,040 crore in the Financial Year (FY) 2020-21 to Rs 54,581 crore in the FY 2021–22. However, the revised estimate (RE) for FY 2020-21 was Rs 46,791 crore, suggesting a decline from the Budget Estimate (BE) owing to the pandemic. The urban sector RE for FY 2020-21 reported the capital expenditure at around 22 per cent vis-à-vis the 42 per cent envisaged in its BE; thus, highlighting the impact on infrastructure projects too.

Public Transport: Augmentation of transport infrastructure of cities in the form of investment in metro rails and buses in Chennai, Bengaluru and Nagpur is an important development. An innovative Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model is envisaged to enable private sector players to enter the domain of bus services. Importantly, the Budget extends the transport outlay to peripheral areas of Tier-1 cities primarily through the greener and cheaper light rail systems. However, an overt emphasis on PPP is problematic. One of the main reasons for limited private investment in infrastructure is the absence of a revenue model, making a large part of the urban infrastructure sector financially non-viable. Lack of enabling PPP legislation, multiplicity of agencies, the inability to select and structure a PPP project, lackadaisical political will towards project implementation and lackluster citizen participation further complicate the entire process of formulation and implementation of PPPs. In fact, the relative success of technically simple projects with small gestation periods emphasises deft crafting of PPP models with a well-defined role of the private sector as well as clear visibility on both costs and risks, making them viable in the long-term. The vulnerability of the urban poor can be addressed through the adoption of an independent regulatory mechanism with the responsibility of accurately assessing as well as monitoring the cost of service delivery by leveraging smart technology and use of a cross-subsidy model to ensure cost recovery at an overall level.

Smart Cities Mission (SCM) and AMRUT: Even after five years, the progress of the SCM has been disappointing and the BE for SCM remains the same between the FY 2020-21 and 2021-22 at Rs 6,450 crore. The RE for FY 2020-21 for SCM was Rs 3,400 crore, almost half of the BE, suggesting a continued trend in the implementation lag. Also, there has been no change in the budgetary provisions for AMRUT as the BE remains the same as 2021-22 at Rs 7,300 crore. As opposed to the centralised one-size-fits-all approach of JNNURM, SCM and AMRUT through the Service Level Improvement Plans, provide, at least on paper, some degree of flexibility in the formulation, approval, and implementation of projects at the State level. Nonetheless, the operationalisation of these schemes portrays a worrisome picture. As the city selection under the SCM is based on the city’s competence and smartness of the proposal, State actors engage themselves in a competitive mode to attract capital investment and to create new institutions like Special Purpose Vehicles that are directly controlled by State institutions to manage the new space. These are headed by the State Government officials and city governments do not have much role in the decision-making processes of the SCM projects, thus eventually weakening the municipal governance structure. The actual decision-making processes have fallen into a pattern of strict investment logic, resulting in preference to larger and costlier infrastructure over the needs of urban deprived communities. Several projects under the SCM (parking facilities or real estate development or commercial real estate) seek to build the financial corpus of the city. Given the SCM’s emphasis on the convergence of funds from other schemes, the possibility of transmission of the inherently unequal nature of fund allocation for Area Based Development projects into them is set to make the policies more exclusionary. The provision of end-to-end support by the Project Development and Management Consultants for planning, design, management and monitoring of urban projects have led to the splintering of resources away from the purview of democratic accountability. On a positive note, 45 smart cities in India have set up Integrated Command and Control Centres (ICCCs) as 24X7 war rooms for creating situational awareness and real-time coordination of emergency response services amid the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, acknowledgmentof the loopholes in the implementation of SCM and AMRUT and some policy reorientation with emphasis on co-producing the bottom-up solutions will be useful.

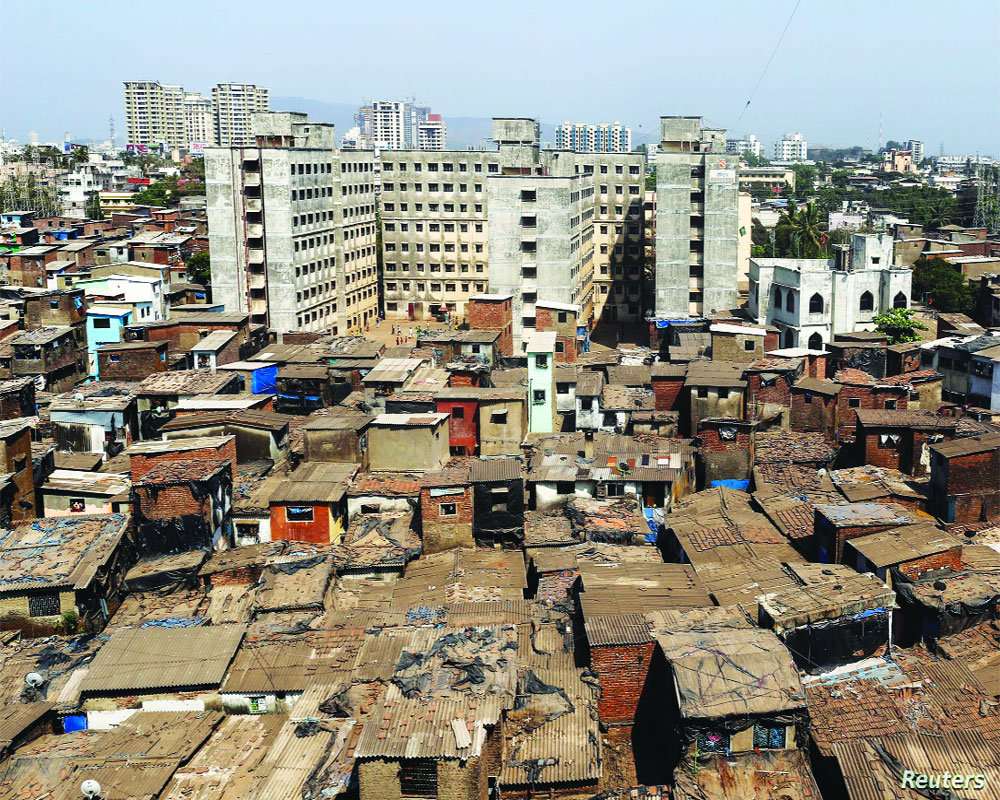

PMAY: There has been a big push in urban housing for the flagship scheme Pradhan Mantri Aawas Yojana–Urban (PMAY-U) with resources also being raised from Extra Budgetary Resources (EBR) such as the Affordable Housing Fund. However, the pandemic has highlighted the focus on the issue of redevelopment of slums, congestion and informal housing. The Budget has provided some indirect benefits for the urban housing sector via, an additional deduction of interest amounting to Rs 1.5 lakh for purchasing an affordable house and tax breaks for the developers of notified affordable housing projects as well as rental housing projects for one more year up to March 31, 2022. The Affordable Rental Housing Complexes for Migrants Workers/Urban Poor scheme, launched in 2020 amid the migrant crisis did not see much of a push in the Budget.

Livelihoods in the lurch: There was an absence of any additional budgetary provisions for urban poverty alleviation programmes like the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana National Urban Livelihood Mission. The Prime Minister Street Vendor’s Atmanirbhar Nidhi (PM-SVANidhi) was launched in 2020, to help formalise 70 lakh street vendors. Till February 2021, more than 21 lakh loans were sanctioned under PM-SVANidhi. But, despite the success of MGNREGS scheme in providing some income security to the rural people and migrant labour and the cash transfer scheme PM-KISAN for farmer households, there is no similar employment guarantee scheme or cash assistance this year for the poor.

COVID-19 has reignited the housing vulnerabilities of the urban poor. It has impacted the real estate and construction sector and highlighted the need for adequate housing, the structural and institutional deficiencies in urban governance and management. India needs to invest in urban infrastructure to bridge the investment deficit and to upgrade the quality of existing services.

The recent approach of making our cities compete among themselves by various periodic rankings such as the Swachh Survekshan, Ease of Living Index, Municipal Performance Index and so on, has demonstrated limited impact. Time and again, various global ranking of cities reveals the precarious state of ours. The FM has attempted to augment urban investment with an emphasis on private financing. Concomitant institutional reforms with an explicit focus on empowered city governments having enhancing capabilities to develop and implement strategies that are feasible and effective in their local contexts is urgently needed. Financially empowered city governments with a clear functional domain can bring self-confidence to our cities which can, in turn, lead us towards fulfilling the vision of a New India and Atmanirbhar Bharat.

Chattopadhyay is Associate Professor of Economics, Visva Bharti University and Senior Fellow, IMPRI, while Kumar is Director, IMPRI and CIVS Fellow at Ashoka University and Asian Century Foundation. The views expressed are personal.