The country cannot continue to rely on the conscience of its judges without going into the root of the problem

Disha Ravi, an Indian youth climate change activist, was granted bail recently by a Delhi court in connection with a case where it was alleged that she was involved in the making of an online toolkit related to the ongoing farmers’ protest last month. Additional Sessions Judge Dharmendra Rana granted her bail, holding that “citizens are conscience keepers of a Government in any democratic nation and they cannot be put behind bars simply because they chose to disagree with the State’s policies.” In a landmark order on bail, Judge Rana went on to state that “the offence of sedition cannot be invoked to minister to the wounded vanity of the Government” and that “difference of opinion, disagreement, divergence and dissent are signs of a healthy democracy.” He added, “An aware and assertive citizenry, in contradistinction to an indifferent or docile citizenry, is indisputably a sign of a healthy and vibrant democracy.”

This is, without doubt, a brave verdict. Little did anyone expect that a judge from the lower judiciary in Delhi would red flag the police and stand up to the State, thereby upholding basic constitutional values of liberty and freedom.

But, here’s the catch! Not everyone in the judiciary is Judge Rana and neither is everyone as lucky as Disha. Munawar Faruqui, a stand-up comedian, was arrested on January 1 this year in a case where he was alleged to have insulted and outraged the religious feelings of a particular community. The Supreme Court granted him bail after more than five weeks of imprisonment noting that the evidence against him was “vague.” The court also said that none of the procedural requirements of arrest, as laid down by the Supreme Court in the 2014 landmark judgment of Arnesh Kumar vs the State of Bihar case, was followed by the police.

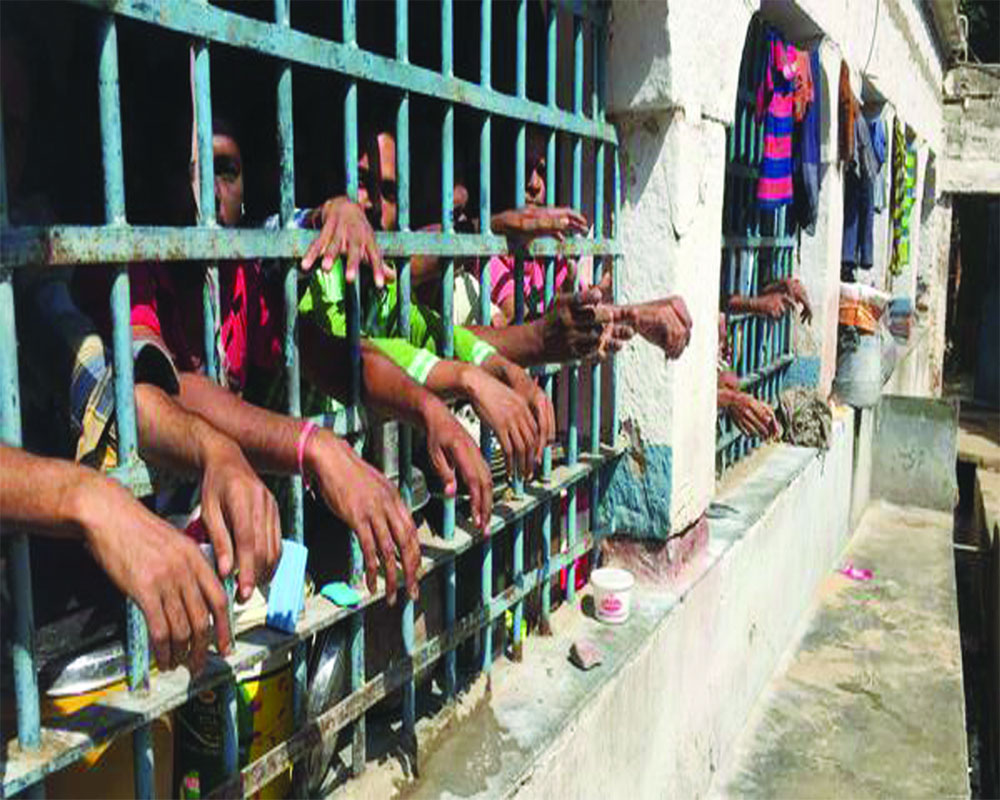

These are, however, only a few examples. The likes of Safoora Zargar, Siddique Kappan, Meeran Haider, Shifa Ur Rehman, Gautam Navlakha, Stan Swamy, Akhil Gogoi and many other common citizens have suffered the uncertainties that involve bail petitions. They were either denied bail for months (in some cases years) or were not granted one at all. This is a big problem! If citizens in this country can be easily put behind bars without a trial, only to be released months later with the help of a delayed intervention by the courts, then constitutional principles will easily turn to dust. Such a situation is even more dangerous when the courts have, in a majority of these cases, eventually ruled that the arrests were either illegal, unwarranted or not necessary. It is, therefore, significant for us to understand that the law on bail in India is highly oppressive. In fact, so much so that it manifests itself in the form of three-tier layered oppression.

Advocate Abhinav Sekhri who happened to argue Disha’s bail plea states that the age-old saying “Bail, not Jail” is in fact a myth. Let us see how. At the bottom of this layer is the State or the executive that has the power to categorise and classify crimes as bailable and non-bailable. So, if tomorrow the State decides that begging is a non-bailable offence — resultantly, all beggars on the streets will be immediately arrested without a warrant and put behind bars. The trial will go on at its own pace and the accused will spend years in prison without being proven guilty. It isn’t shocking, therefore, that India is the only country where 70 per cent of prisoners are undertrials, most of whom are poor and are languishing in jails for years.

In the middle of this layer is the police that has the power to invoke a non-bailable offence against an accused. Even though the law grants certain procedural safeguards, the police has to work at the whims and fancies of its political masters.

Lastly, at the top of the layer is the judiciary, which, in bail petitions, is completely guided by the conscience of the respective judges. There are no statutory objective criteria and individual judges are required to judge each case on its own merits. Such a situation poses itself as an irony as well as a set of contradictions. On the one hand where the Constitution grants essential rights such as “equality before the law” and “equal protection of the law”, procedural due process and substantive due process, liberty and right to life to every citizen of this country, bail petitions, on the other hand, are heard with no objectivity or set criteria. Cases of identical nature are dealt with differently by different courts and different judges.

Therefore, a solution lies in getting to the root of the problem. If we have to reduce the arbitrary power of the State, we need to review our antiquated laws on arrest and custody that were enacted by an oppressive British regime to control Indians and curb dissent during the freedom movement. An 1861 Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) cannot continue to decide the fate of millions of Indians in Independent India. Laws of sedition that give unbridled rights to the executive to act arbitrarily need to be done away with. At his sedition trial, even Mahatma Gandhi had unequivocally pointed out that Section 124-A was a “prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen.” Countries like New Zealand, the UK and Australia have already gotten rid of their sedition laws and it is time India follows suit.

At the second level, we need to fix individual responsibility of police officers who, under the CrPC have been given the powers of arrest and detention. An analogy can be drawn with International Humanitarian Law. During the war crimes trials that took place after World War-II, many defendants invoked superior orders as a defence, claiming that they could not be held accountable for the crimes committed because they were only following the orders of their superiors. The case law of these trials eventually resulted in the development of a customary rule applicable in all armed conflicts, whereby obeying a superior order does not relieve a subordinate of criminal responsibility, if the subordinate knew that the act ordered was unlawful, or if he should have known so because of its manifestly unlawful nature. Where an order is manifestly unlawful, all combatants have a customary duty to disobey. Similarly, in domestic laws, the police officer carrying out an illegal arrest without following due process of law needs to be held accountable even if he was following the orders.

Once we have reviewed and reclassified our laws into bailable and non-bailable offences, fixed the accountability of individual police officers, let the courts be guided by objective statutory criteria and not by their subjective conscience. The reason why we have to thank the conscience of judges like Rana is because of the subjectivity that pervades our bail laws.

The optimism that our judiciary has and will continue to have the likes of Judge Rana is a hope and hope alone cannot be our saviour in times of extreme distress. We have to act. As Benjamin Franklin rightly said, “Justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are.”

Tiwary and Singh are from the National Law University, Visakhapatnam. The views expressed are personal.