Far behind Nepal, Bangladesh, Pak

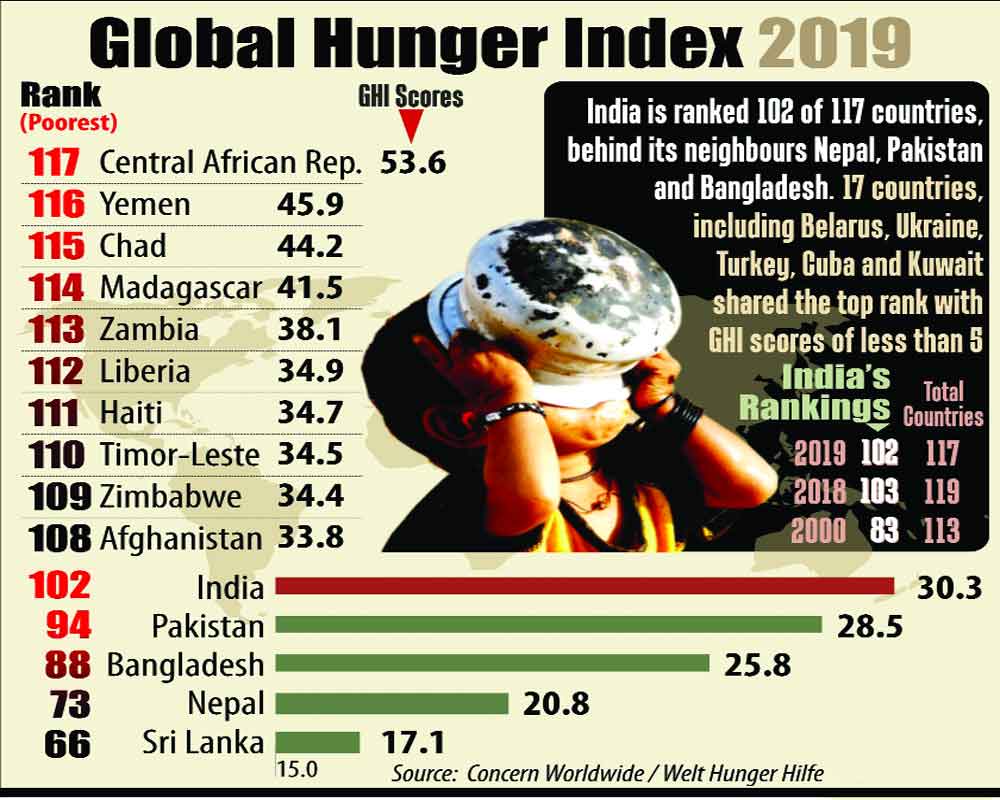

On hunger index, India has slipped from the 95th rank in 2010 to the 102nd in 2019, behind Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan. In 2018, India occupied 55th rank.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) measures the level of hunger and undernutrition worldwide. The four indicators for the index are undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting (weight for age) and child mortality.

A report released by the International Food Policy Research Institute points out that among the 117 listed countries, 47 are on ‘serious’ and ‘alarming’ hunger levels and one in ‘critically alarming’.

India’s dismal performance on hunger is directly linked to the high level of child undernourishment. Over one in every five children in India is “wasted” (low weight for height), the highest for any country in the report.

India is way behind its much poorer neighbours such as Nepal (73rd), Sri Lanka (66th), Bangladesh (88th), Myanmar (69th) and Pakistan (94th), the report said.

China is placed 25th and moved to a ‘low’ severity category and Sri Lanka is in the ‘moderate’ severity.

The future does not look so bright for India in tackling hunger in case business as usual continues with climate change further worsening under-nutrition, said the report.

India’s current GHI score, 30.3, reflects an improvement in some of these indicators compared to the years preceding it. On GHI, India scored 38.8 in 2000, 38.9 in 2005, and 32 in 2010. The IFPRI report, however, says this year’s rankings cannot be directly compared to the rankings of previous years because of changing parameters and the addition/subtraction of countries counted in the report.

“Because of its large population, India’s GHI indicator values have an outsized impact on the indicator values for the region. India’s child wasting rate is extremely high at 20.8 per cent - the highest wasting rate of any country in this report for which data or estimates were available,” the report said.

“Its (India) child stunting rate, 37.9 per cent, is also categorised as very high in terms of its public health significance. In India, just 9.6 per cent of all children between 6 and 23 months of age are fed a minimum acceptable diet,” it said.

The report also took note of open defecation in India as an impacting factor for health. It pointed out that as of 2015-2016, 90 per cent of Indian households used an improved drinking water source while 39 per cent of households had no sanitation facilities.

In 2014, the Prime Minister instituted the “Clean India” campaign to end open defecation and ensure that all households had latrines, the report said, adding, “Even with new latrine construction, how- ever, open defecation is still practised. This situation jeopardises the population’s health and consequently children’s growth and development as their ability to absorb nutrients is compromised.”

The GHI ranks countries on a 100-point scale, with 0 being the best score (no hunger) and 100 being the worst. Values less than 10 reflect low hunger, values from 20 to 34.9 indicate serious hunger; values from 35 to 49.9 are alarming; and values of 50 or more are extremely alarming.

The report warned that climate change was causing alarming levels of hunger and making it more difficult to feed people in the world’s most vulnerable regions. Climate change was affecting the quality and safety of food and worsening the nutritional value of cultivated food, it stated.

The report pointed out that while there has been progress since 2000, the world has a long way to go to achieve the ‘zero hunger’ target.

Highlighting that climate change affects the quality and safety of food, the GHI report said, it can lead to production of toxins on crops and worsen the nutritional value of cultivated food.

Citing an example, the report stated the climate change can reduce the concentrations of protein, zinc, and iron in crops. As a result, by 2050 an estimated additional 175 million people could be deficient in zinc and an additional 122 million people could experience protein deficiencies.

“Human actions have created a world in which it is becoming ever more difficult to adequately and sustainably feed and nourish the human population. Ever-rising emissions have pushed average global temperatures to 1°C above pre-industrial levels,” the report said.

“Climate change is affecting the global food system in ways that increase the threats to those who currently already suffer from hunger and under-nutrition,” it said.

The GHI report praised the progress made by Bangladesh, attributing it to “robust economic growth and attention to ‘nutrition-sensitive’ sectors such as education, sanitation, and health”.

Similarly, Nepal has shown the highest percentage change in its ranking since 2000 according to the report, which attributed it to increased household assets (a proxy for household wealth), increased maternal education, improved sanitation, and implementation and use of health and nutrition programmes, including antenatal and neonatal care.

According to the report, 43 countries out of 117 countries have levels of hunger that remain serious. And, 4 countries Chad, Madagascar, Yemen, and Zambia suffer from hunger levels that are alarming and 1 country Central African Republic from a level that is extremely alarming.