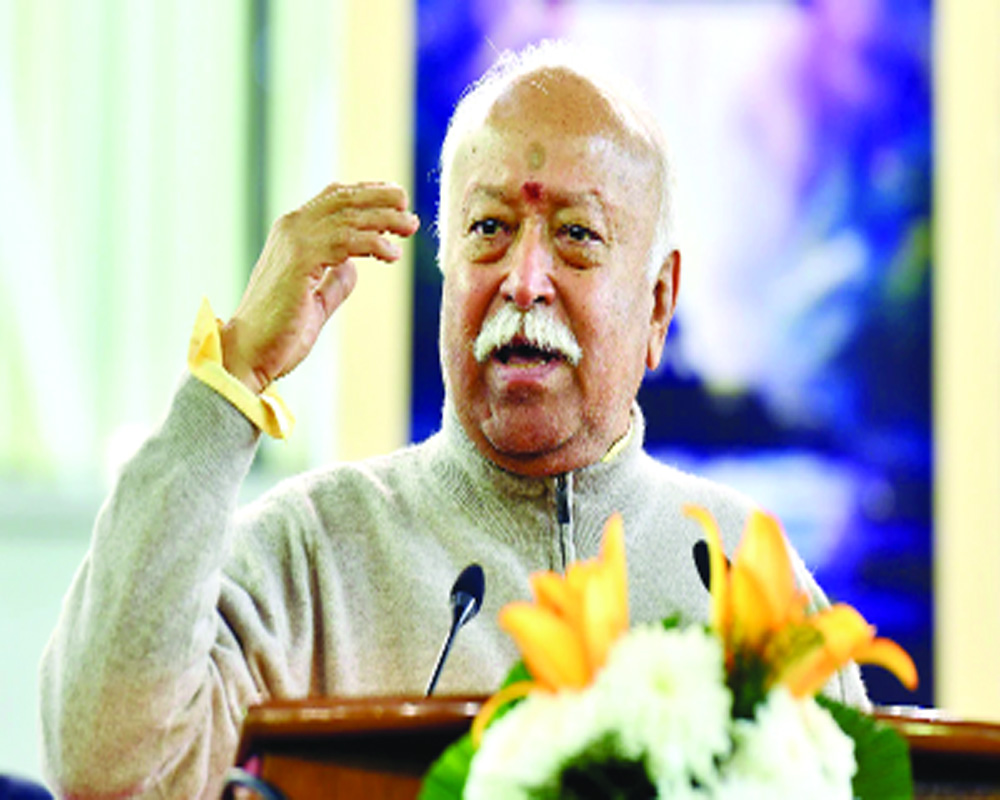

Highlighting the risks posed by divisive narratives such as ‘Mandir-Masjid’ disputes, Mohan Bhagwat stresses the importance of embracing India’s pluralistic identity

Delivering a Sahjeevan Vyakhyanmala series lecture on the topic, India—the Vishavguru, the RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat expressed his concern over the recent upsurge of ‘Mandir-Masjid’ disputes and pointed out: “After Ram Mandir, some think they can become leaders of Hindus by raking up similar issues in new places”. Rejecting the practice, he said, “This is not acceptable.” Echoing his comment on Gyanvapi Masjid that “We look for a Shivling beneath every mosque,” implying that we should not, he cautioned: “The days of hegemony are gone,” and that now “People choose their representatives, who run the government.” Questioning the “language of dominance,” he acknowledged the pluralistic nature of Indian society, where ‘tradition’ allows people to live in harmony while following their respective faiths. Drawing a comparison of India with the world, where similarity is the principle of unity, for India, he said, “Diversity is an ornament of unity, and we should respect and accept it.”

Rejecting hatred, malice, enmity, and suspicion daily under the burden of the past, he ruled out the ‘majority-minority’ binary and emphasised, “Everyone is equal here.” To be a Vishavguru, India should be a nation of people who can rise above caste and religious differences. By what he has said, Bhagwat has targeted more than one point while acknowledging the reality of about 200 million Muslims besides the Christians, Sikhs, and others in India, on the one hand, and the geopolitical realities, on the other.

If that is so, then the word ‘Hindu’ needs to be accepted as an Arabic-Persian cognate of the Sanskrit ‘Sindu’ and ‘Hindustan’ as a reference to the land of Hindus, i.e., the people living beyond the river Sindu, but not a place of and for the people of a specific religion. The historical chronicles state that the river ‘Sindu’ was pronounced as ‘Indus’ by the Greeks and ‘Al-Hind,’ which later became ‘Hinds’ or ‘Hindus’ by the Arabic Iranians.

The Greeks called ‘the land of Indus’ India, while the Arabic-speaking people called the region ‘Hindustan.’ It was a reference to the geographical region of old Punjab. The land of Hindus i.e. the people of river Sindu, called Hindustan or India in the above sense, is a land of several religious faiths, such as Shaivism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, besides the principles of ancient Vedas and Puranas, and the word ‘Hindu’ has been a geographic and a cultural identifier to distinguish between the indigenous people and others who came as traders or invaders, like Muslims, Christians, and Jews, etc., at the initial stages of their entry into the region; the distinction, however, did not mean religious opposition.

It only acted as an identifying communicative ‘sign’: for communication is organised on two axes: the axis of similarities and the axis of differences. The people from the ‘other’ lands gradually became the people of the land called Hindustan, or India, settling permanently and adding to the diversities on the land of the river Sindhu.

Since there is no definite founder and no single holy text to establish a religion called ‘Hinduism,’ it remains only a set of socio-cultural practices while the people practice a variety of their respective religious worship.

The words ‘Hindu’ and ‘Hindustan’ have remained signifiers for the geographic-cultural practices until projected as a religious and national identifier in the early twentieth century in opposition to the colonial rule and in reaction to the Khilafat Movement by the Muslims in support of the Turkish Ottoman Sultan during the freedom movement of India.

The Indian national identity was codified by a section of people as a Hindu national religious identity and an Islamic national identity, dividing the people on religious lines. The division was perpetrated by the colonial British in more than one way, leading to the partition of India.Since 1947, free India has been a sovereign state nation, though it should have been a state of cultural nations politically united as a federal political state, settling the issue of religious nations forever. Yet India has stood the test of its unity in diversity with some collisions on the sidelines.

The internal dynamism of society and state is its continued collision and cohesion in their weaving: the more complex a society or a state is, the higher its level of collision-cohesion dynamics. For the well-being of the land and its population, the political drivers must turn the power to strengthen ‘diversity’ against the ‘forced homogeneity’ as a principle of organisation. But with the rising assertion of Hindu religious identity and a Hindu nation-state over Hindu geographic-cultural identity juxtaposing with the recent upsurge in ‘Mandir-Masjid’ controversies, rightly perceived by Mohan Bhagwat, the danger to the unity and cohesion is more imminent than not.

The sooner the ideologues of identities understand it, the better it is for the people living together for centuries. Mohan Bhagwat seems to have realized it, and rightly so, he has underplayed the slogan—’one nation, one people’—stating’, “Without Muslims, Hindutava is incomplete”: Hindus and Muslims are different but complementary. Hindustan, or India, or Bharat, is a land of diversities, and only by choice of the ideology and practice of inclusion, it can become Vishavguru.

To be the Vishavguru is to experience and accommodate more diversity.The Vishav, i.e., the universe, is organized into networks of similarities and differences, yet the precursor of life on earth is the ‘difference’ that engenders diversity.

Mohan Bhagwat’s nuanced remarks underscore the importance of unity amidst diversity in India’s journey toward becoming a Vishavguru. Acknowledging India’s pluralistic fabric, he emphasised harmony over divisive narratives like ‘Mandir-Masjid’ disputes and rejected notions of religious hegemony. Bhagwat traced the historical and cultural origins of terms like ‘Hindu’ and ‘Hindustan,’ advocating for their geographic and cultural significance rather than a singular religious identity. He urged political and social leaders to strengthen diversity as a foundation for national cohesion. By embracing inclusion and mutual respect, India can truly embody the universal ideals required to be a global guide and leader.

(The writer is Professor (Retd), Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, Vice-Chairman, Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage, New Delhi; views are personal)