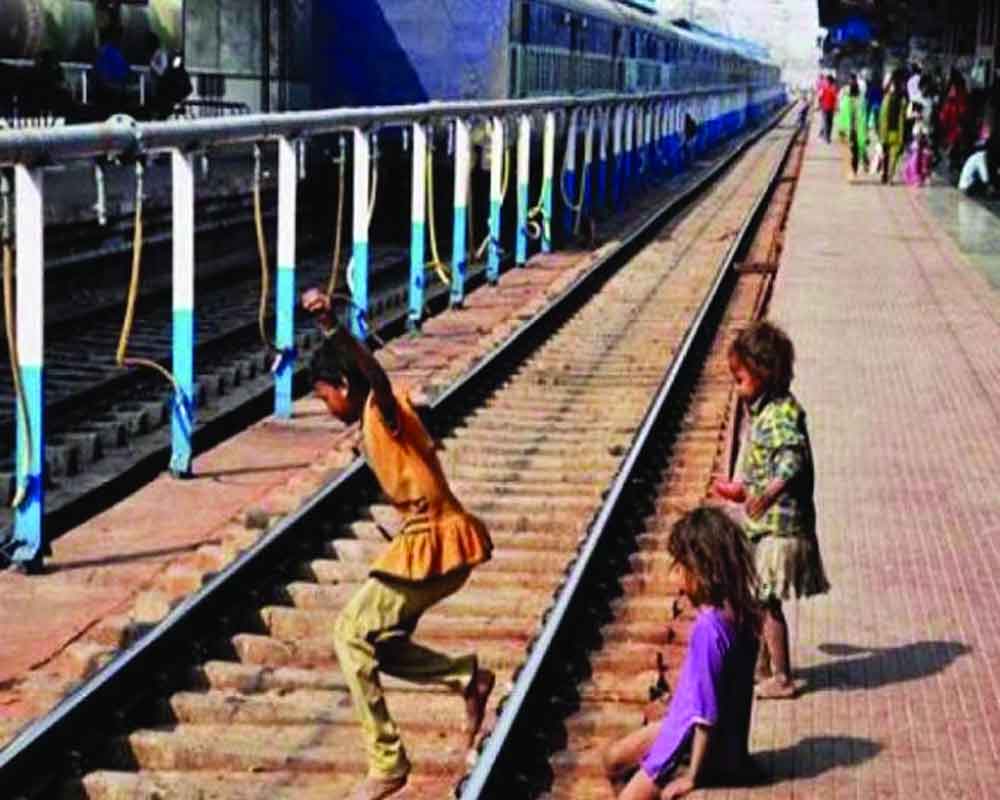

Children who lived off at rail platforms face harsh realities

The Covid-19 pandemic had left a telling impact on the street children, particularly those who lived off the railway platforms. The children are coming back to the railway platform after they had left following the shutdown of the train operations and excessive restrictions afterward for the entry and exit at the stations. The overall trend was echoed by Railway Children India (RCI), which works with street children and communities around stations, including running initiatives like funding the operation of toll-free, helpline booths for children. “The number of children being rescued is nowhere near to the pre-lockdown era (as of July 2021). From 500 children every month in pre-lockdown to not more than 100 or maximum of 120 a month (in July 2021) to 250 a month in December 2021,” Navin Sellaraju, CEO, RCI, said, based on the experience at about 10 stations of Indian Railways.

Another NGO working in Central India explained that it saw a much lesser number of children being rescued since the Covid-19 struck. The trend of drop in the number of children surprises Sellaraju a bit, who knows that the root causes that were forcing children onto platforms or getting trafficked have not changed. “Rather, COVID-19 made the circumstances of those children more difficult. Most of the children that RCI rescued were from unemployed families, small farmers, and vegetable vendors,” Sellaraju said.

Sellaraju reckons stringent screening at entry-exit points at large railway stations, higher restrictions, and a drop in running unreserved coaches (the railway only restarted operating these in 2022), which are easy to access for the children may have led to an overall drop in the numbers of children found on platforms in the concerned time-periods. Other stakeholders feel many children have changed their mode of transport from trains to buses, and so have traffickers, who lure children into different cities. Also, traffickers are engaging in newer methods in the post-pandemic time.

A stakeholder from Salaam Balak Trust, a charity that works with street children, including children in contact with railways, explained, “Such children can be broadly grouped into those who lived around stations and came to stations for some time to earn their living; those who were lost while traveling in trains and those who used trains to escape difficult family situations, including poverty. With trains and stations closed for a good part of the year (2021), naturally, there were no new arrivals. However, those who stayed with families near stations stayed with their families; and the rescued kids who were there in our shelters stayed put in the shelters.”

But almost all stakeholders agree that the pandemic-induced conditions have made the children more vulnerable to adversities, including trafficking. Even according to official numbers shared by the Railway Police Force (RPF), the children rescued from traffickers at railway stations saw an increase in 2021. About 492 children were rescued from trafficking in 2021, up from 181 in 2020, 361 in 2019, and 367 in 2018.

The pandemic led to the death of parents, illnesses, and job losses, pushing families to poverty, and prompting an increase in child labor, said an International Labour Organisation (ILO) and UNICEF report of 2021, estimating that in early 2020, 160 million children (one in ten children globally) were involved in child labor. Stakeholders agree that there’s a need for the social inclusion of such vulnerable children who are in contact with the railways at its stations or premises and those who are on the streets be provided with identity cards. (Concluded)

The article is written as a part of Work: No Child’s Business (WNCB) fellowship.

The writer is a senior journalist based in Delhi ( Charkha Features)