Negotiations on the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan stirred high emotions yet Nehru pulled it off, writes Uttam Kumar Sinha in his new book Indus Basin Uninterrupted... An edited excerpt:

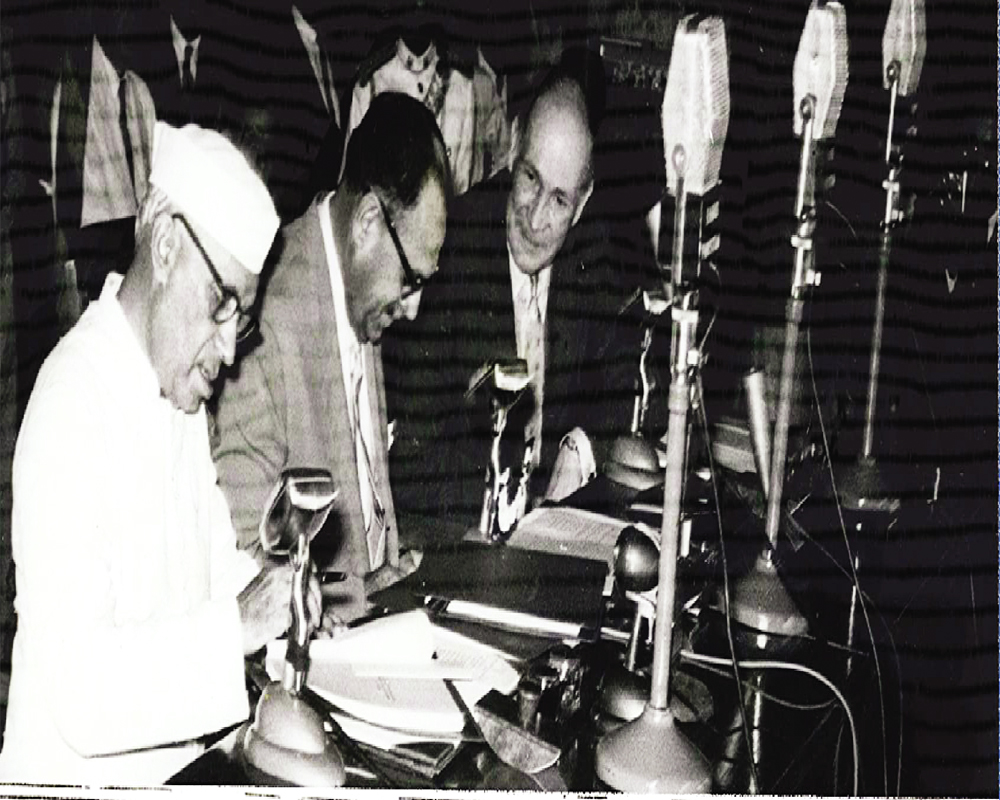

Parliament was in session until 9 September 1960 and the Indus Waters Treaty was signed on 19 September 1960. The Lok Sabha, the lower house, was not in full knowledge of the provisions of the treaty or whether it was ratified. It was not clear whether the government had consulted the leaders of the recognized all-India parties as to how the treaty would affect India. The opposition felt strongly that India had yielded to Pakistan’s terms at the cost of its own interests. In a motion for adjournment in the Lok Sabha on 16 November 1960, Narayan Gore, the leader of the PSP, questioned Nehru’s statement a couple of days previously that the IWT had been ratified. Correspondingly, a young parliamentarian, representing Balrampur constituency, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, sought clarification on the issue and raised a ‘question of privilege’. Making his submission without entering into an argument, Nehru responded: “This was ratified, I think, on the 24th of September. On the 8th October, the Pakistan Government was informed that we have ratified it. It is one thing to ratify a thing; and it is another thing to have the formalities of it, the exchange of what are called the ‘Instruments of Ratification’. That is a technicality.”

Vajpayee, whom Nehru had predicted would one day become the country’s prime minister, responded with pointed urgency, “May I submit that the ratification of the treaty is not complete until the exchange of Instruments takes place.” Peeved, but not disregarding parliamentary methods, Nehru replied, “. . . the exchange of instruments is a technicality to which the honourable member, perhaps, has not paid attention.” Sitting in the House and perturbed over the lack of meaningful debate, the renowned Odia writer Surendra Mahanty of the Ganatantra Parishad sharply observed that the treaty “. . . is agitating the minds of the people and the government must come forward with this motion.” What began as a procedural issue opened up to a long debate a few weeks later on 30 November 1960 that not only sought various clarifications of the details of the treaty but also prised open old wounds and revisited the history of the India-Pakistan water dispute.

The pulse-beat on the treaty signed by Nehru was not healthy. Several mainstream newspapers had castigated the government for giving in to Pakistan, making “...concessions after concessions...” as the negotiations progressed and even “...yielding to Pakistan’s wishes...” Bhagirath, published by the Ministry of Irrigation and Power, in its editorial captioned ‘A memorable agreement’, noted with no triumph, “This attitude of steady negotiations have lasted over more than a decade and called for considerable patience and sacrifice on the part of India and involved a heavy gift of money and water supply from our rivers for a further period of 10 years with both of which India could well do for herself in this crucial period of the growth of our economy.”

In Rajasthan, a strong Congress belt, the mood of the state over the treaty, which it always viewed with trepidation, was hardly encouraging. Harish Mathur, a Congressman representing Pali, unflinchingly said on the floor of the House, “The progress and the developmental programmes will be retarded and it is all to the advantage of Pakistan.” A number of parliamentarians were of the view that, had India conceded to the needs of Pakistan in 1948 as a ‘human consideration’, the treaty would have possibly not been required and would have also saved tonnes of paperwork and notes, and many a blush. Was then the treaty a sheer giveaway? Would it have been better for India to have conceded in 1948, when Pakistan’s demand was limited, rather than to have become so generous in the negotiations leading up to the treaty? As things developed, Pakistan’s demand became bigger and bolder. “I wish,” said Mathur, “Our Government takes note of the feeling in this country. It is not that our over-generousness should be at the cost of our own people and at the cost of the development of this country.”

Nehru’s government had a lot of explaining to do on a treaty that seemed to backtrack from its earlier position. In preparation for a meeting between the Indus negotiators in Rome in 1958, Nehru had expressed, “I am not at all happy about the way our discussions with the Bank are proceeding in regard to this matter. Step by step, we are dragged in a direction unfavourable to us.” A few months earlier, the newly appointed irrigation and power minister, S.K. Patil, an undisputed leader of Mumbai who was regarded as Sardar Patel’s man in Maharashtra, had stated firmly over the prolonged Indus negotiations that “... India will not wait indefinitely for a settlement, ignoring the needs of her people . . .” and that not a drop of water will be given to Pakistan beyond 1962.

A feeling had emerged that India had agreed to terms that were acting against its own advice and at the cost of its own people. It was calculated that India would lose about 5 million acre-feet of water from the Chenab, resulting in a perpetual loss to the country to the extent of about Rs 70-80 crore per year. The Lok Sabha was keen to understand the advantage or, as many felt, the disadvantage of the treaty. Ashok Mehta, who liked to challenge Nehru on issues of decentralization and nationalism and was later invited by Nehru to assume the deputy chairmanship of the planning commission for which he (Mehta) was expelled from the PSP, summed up India’s position, “This is a peculiar arrangement wherein the other side’s obligations are not brought into the focus at all and unilaterally we come forward to make significant concessions.”

Right from the time of the Nehru-Liaquat Agreement in 1950, India, it was felt, often undermined its interest for the larger cause of peace with Pakistan. The Nehru-Noon Agreement of 1958 to end disputes along the Indo-East Pakistan border areas, resulted in an exchange of enclaves and a part of Berubari went to Pakistan, apparently without the West Bengal assembly being consulted. West Bengal was up in arms and the Supreme Court, in a unanimous judgment, held that Article 253 was not sufficient when it came to the question of cessation of national territory. While it was the privilege of the executive to come to international agreements which Nehru exercised, within the democratic framework, it was equally incumbent to consider the opinion and the sentiments of the country and the House. Nehru was chastised repeatedly for placating Pakistan. The issue prompted Arun Guha, a Congress representative from West Bengal, to ask, “...Has Pakistan responded in any friendly manner?”

Nehru was not averse to participating in the discussions on foreign policy or economic planning. In fact, he was more than up to it, viewing it as a test and a demonstration of his ability and power unlike his unequivocal stand on social reforms which he candidly confessed to not being knowledgeable about. Nehru had faced the heat of the Parliament over the Tibetan crisis in 1959 with many opposition leaders, including those of the PSP and Jan Sangh, except the Communist Party of India, demanding that the government review its policies of India-China friendship. The spate of adjournment motions on Chinese aggression on Tibet had rattled Nehru as he defended his government’s decision to accept Chinese suzerainty over Tibet as a rational choice. The debate on the Indus treaty offered similar intensity and presented some very uncomfortable facts for the government to respond to.

Excerpted with permission from Indus Basin Uninterrupted: A History of Territory and Politics from Alexander to Nehru, by Uttam Kumar Sinha, Penguin Random House, Rs 799