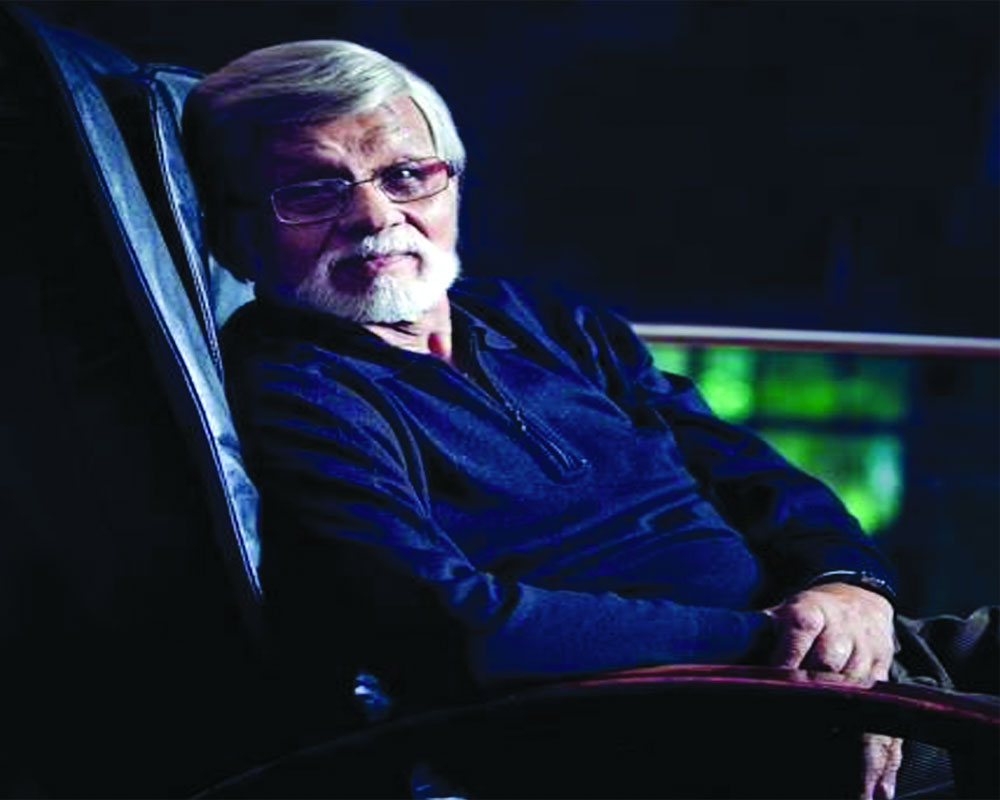

Our lives are defined by the experiences and relationships we have through the years. The work of acclaimed artist, architect, sculptor and writer, Satish Gujral, who passed away on Thursday at the ripe old age of 94, was influenced by his multi-faceted passions. By Team Viva

Gujral brothers

Born in Jhelum in pre-Partition Punjab, Gujral was the brother of the late Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral and was awarded India’s second-highest civilian honour, the Padma Vibhushan in 1999. The three Gujral brothers belonged to a prodigious family. Satish’s elder brother, IK Gujral, was an important voice in the Congress party and this family went onto to create their own realms in the pages of Indian history. Refugees after India’s Partition, he would often recall how they were given 200 square yards and later, how a 600 square yard plot at Nizamuddin was sold off and they bought a piece of land at Jor Bagh for an auction.

Education and Mexico

Gujral lost his hearing power at the age of eight. But his inner creativity had a resilience that was deep and resonant. He studied at JJ School of Art in Mumbai and was sent to Mexico on a scholarship in 1952. His apprenticeship with David Alfredo Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, two artists who led that country’s muralist movement became the turning point of his artistic odyssey. In an interview in 2000, he had said, “I was a leftist in those days. I wanted to paint on the walls like the Mexican muralists. But later, I realised that art shouldn’t be used as a propaganda. Everything cannot be rebellious. I was always given opportunities and was grateful for them. I decided that art must be a tool to initiate dialogue with people. I started advocating public art in my country. When I did murals on the walls of Panjab University, Chandigarh, Shastri Bhawan and Oberoi Hotel, among many others, I know I was recreating stories of experience and learning.”

His first job was of a graphic designer in Shimla. While working, he painted refugees and their pain. “After a long time, I realised that I didn’t paint Partition but I painted my own sufferings,” he had said in the same interview.

When he came back from Mexico to Delhi, he wanted to sell his works. He went to Ravi Jain’s Dhoomimal at Connaught Place. At that time, there was also Kumar Gallery (set up in 1956) and he gave a few works to Virender Kumar to begin the Kumar Gallery, which stands as one of the best in the nation today.

Among his architectural wonders is the Belgian Embassy in Delhi, which was selected by the International Forum of Architects as one of the 1,000 best built buildings in the 20th century all over the world.

Dialogue between tragedy and solidity

It was Gujral’s paintings that held their own in terms of narratives and depths of contextuality. His subjects were concerned with the dialogue between single tragic figures and buildings set down around them with all the apparent solidity of a stated fact. This dark, parched environment was part of a locked-in world, in which figures and buildings stand among the soundless fall of shadows, so that the viewer’s inspection seemed like a trespass. There was something hauntingly Indianesque but he consciously refused to exploit traditional Indian styles. Perhaps, this quality lay in the dry colour, the texture that was sunburned and gritty, that was dragged across the surface to create a uniform mat texture.

His paintings had subtleties of colour that played across their harsh surface like hints of a mirage in a dry desert. But they had an elusive quality that retreated into profundity too. Eventually, their seeming solidity dissolved into sliding planes of colour.

Gujral’s sculptures

Satish Gujral’s wooden sculptures were a blend of India’s mythology and his brilliance lay in bringing in different mythic metaphors into his sculptural language. Created out of oil on burnt wood, with leather, cowrie shells and ceramic beads on ply board, this work is an abstract representations of deities-interspersed with vermillion and gold colours. He explored the spatial elements of depth and texture through a unique technique and his multi-faceted, contemporary sensibilities.

Scorn for the Progressives

His scorn for the Progressives was well known. He challenged the view that the Progressives brought international modernism to Indian art, a view expressed in his autobiography. “The idea of the Bengal school of a modern Indian art was sound but its practitioners lacked the talent, the genuine inspiration to carry it out. The progressive art group could have given further impetus to the idea of the Bengal school, but killed it. What began in the 60s could have begun in the 40s.”

“We relate modernity to the West; what is not Western is not modern. Judging by that yardstick, our modernity is spurious. But if you judge the difference in attitudes to the past, the determination to infuse contemporary values, then I would say modernism has always existed. In the visual arts, its present source would not be the progressive art group but the Tagores,” was his observation.