The Epstein mirror: How power and money colluded in plain sight

It is ugly. It is disgusting. No one knows whether he died by suicide or by some other, more carefully arranged ending, designed to bury what he knew and whom it protected. But this is what the hypocritical West looks like when the curtain slips. You praise a person as long as you do not know what sits inside him; you despise him the moment the rot begins to breathe in public. Jeffrey Epstein tells a complete story of what America and the West have become, not because he was exceptional, but because he was ordinary in the ways that matter most. From Chomsky to Bill Gates, Elon Musk to Trump, from New York boardrooms to Westminster salons, and the long, awkward associations with figures such as Peter Mandelson, the same putrid pattern repeats. This is not about monsters hiding in basements. This is about appetite, denial, and the theatre of respectability.

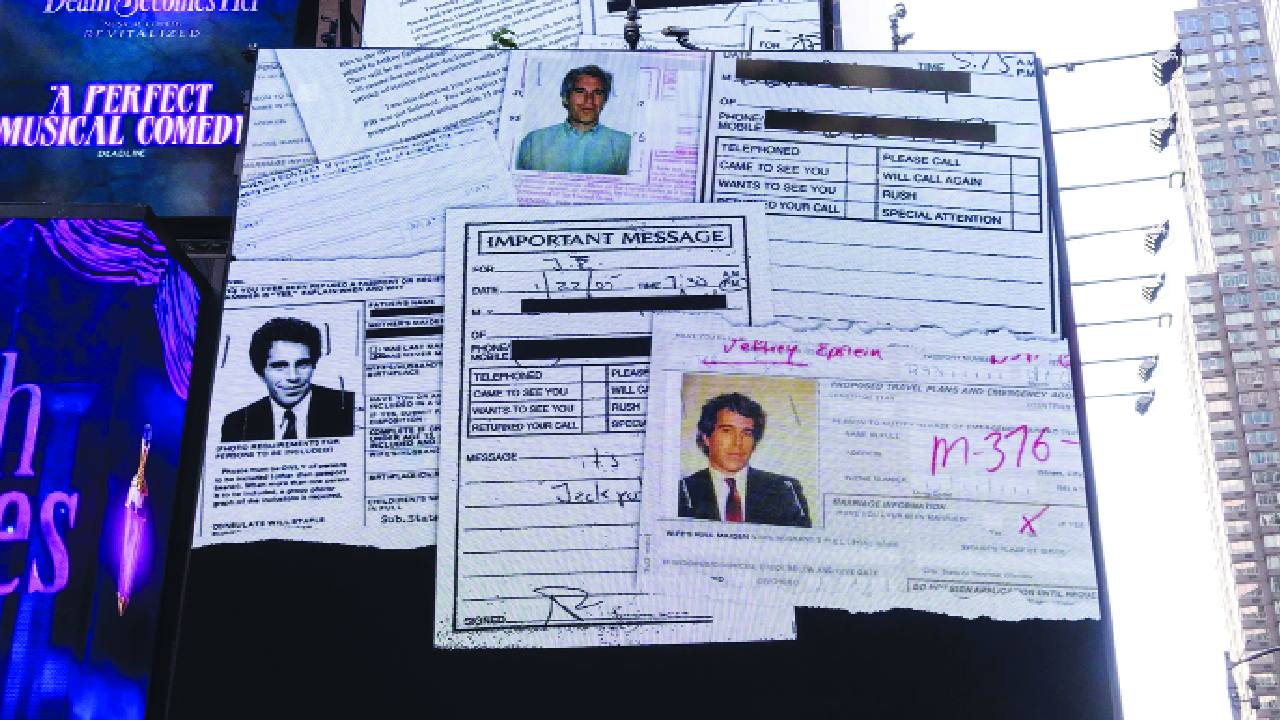

Last week, as millions of pages from the so-called Epstein files began circulating again, another artefact surfaced alongside them: the last known interview Epstein ever gave, recorded with Steve Bannon. It is not a confession. It is not remorseful. It is something far colder. A man speaking as if the trial were civilisation itself, not him.

He speaks of finance as something closer to mysticism than economics. Leaders, he suggests, do not understand the systems they claim to govern. “You weigh and measure every day,” Bannon tells him. “You weigh and measure people. You weigh and measure leaders. You weigh and measure economies.” Epstein replies, calmly, “I don’t even know what it means to be measured.” Not as evasion, but as assertion. Measurement, in his account, is approximation, an abuse of language, a crude imposition on reality. Precision itself becomes a fiction.

He repeatedly returns to this refusal. Asked when human life begins, he says the question itself is malformed. “You’re asking me to measure something again.” Pressed further, he retreats into paradox, invoking Zeno, quantum behaviour, and the impossibility of exactitude. Hair, skull, height, decimals. The question dissolves into semantics. Nothing lands. Nothing sticks.

This is the rhythm of the interview. Whenever responsibility approaches, the language lifts off the ground.

Epstein frames history as a long record of misunderstanding. Newton, he says, could describe motion but not explain it. Quantum physics only widened the mystery. “We just cannot explain,” he repeats. Electrons are not things but clouds. Solids are not solid. At small scales, reality collapses into probabilities. From this, he draws a broader claim: that science, mathematics, and formal systems are the wrong tools for understanding life. “No really new ideas have come out,” he says of modern institutions, because they are trapped using the wrong instruments.

He applies this logic everywhere. Markets are not calculable; they are felt. Traders succeed through intuition, not models. Mathematics follows action, never the reverse. Measurement arrives after the fact, to justify what instinct already decided. Crises are not moral failures; they are structural inevitabilities. Collapse is not crime. It is mechanics.

Rockefeller and JP Morgan appear in his telling as honest predators, men who never pretended capitalism was humane. Modern leaders, by contrast, are described as symbolic figures, trapped inside systems they cannot read, repeating language about growth and stability while liquidity moves independently of them. Whether this is true is almost irrelevant. What matters is that Epstein speaks as if proximity to power grants ontological superiority. Understanding, in his world, is not earned; it is inherited through access.

The files released alongside this interview make the same argument without words. Names recur. Flights recur. Dinners recur. Foundations recur. What disappears is responsibility. Everything is coincidence. Everyone was only passing through. The documents do not need to prove every allegation to expose the structure. Power does not operate through direct orders. It circulates. It accumulates. It protects itself through diffusion.

When Bannon asks whether institutions should take money from someone like him, Epstein does not deny the question’s legitimacy. He reframes it. He speaks of polio vaccines in Pakistan and India. He asks whether mothers would refuse money if told it came from the devil himself. “I don’t care, I want the money for my children,” he imagines them saying. Utility overrides origin. Outcome erases source. Pressed further, Bannon asks the question directly: is your money dirty money? Epstein answers simply: no. He earned it — advising terrible people, perhaps, but earning it nonetheless. Ethics, he suggests, are always complicated. This is not a defence. It is a declaration of how the world works.

At one point, Bannon asks whether Epstein thinks he is the devil. Epstein does not laugh. He deflects. The devil, he says, scares him. Satan, he notes, was brilliant, an archangel who rebelled because he could not be number one. The comparison lingers without resolution. The interview ends shortly after. No absolution. No reckoning.

What emerges from this last interview is not a man in denial, but a man entirely comfortable with abstraction. Shame is translated into systems. Harm dissolves into theory. Victims never appear as subjects, only as variables implied offstage. Consciousness, intuition, the soul all enter the conversation only to

establish that nothing essential can be pinned down.

The files show how well this posture was accommodated. Universities accepted money while insisting they were neutral. Politicians appeared alongside him while assuring themselves they were merely polite. Media figures attended dinners while calling it observation. Everyone performed a role and trusted that performance itself was protection.

The West likes to describe itself as transparent, but it survives through selective blindness. Confession is demanded from the weak. Silence is granted to the useful. When scandals erupt, they are framed as deviations rather than products. Epstein’s story is intolerable precisely because it refuses that comfort. He does not apologise for understanding the rules as they are practised rather than preached.

There is an instinct to personalise the horror, to catalogue names and savour disgrace. That instinct misses the deeper point. Epstein’s circle was not united by ideology or loyalty, but by convenience. People who would never share a moral code shared aircraft. People who condemned exploitation in public tolerated it in private. This is not casual hypocrisy. It is structural compartmentalisation.

The West has learned to split its self-image from its conduct, to celebrate progress while outsourcing its costs to the unseen. Epstein did not disrupt this order. He navigated it fluently. Financier, philanthropist, intellectual — he shifted registers with ease. The files show how often this worked.

His death resolved nothing. It converted a living problem into an archival one. Documents replaced testimony. Speculation replaced trial. The anger dispersed into procedural arguments. Meanwhile, the structures that enabled him remain untouched: reverence for wealth, fear of disruption, and the confusion of success with legitimacy.

What makes the interview disturbing is not bravado. It is tone. Epstein speaks without urgency, without fear, as if describing weather patterns. Consequences are acknowledged but not absorbed. Effects are catalogued without weight. In another setting, this might be called rational detachment. Here, it reads as something closer to anaesthesia.

The West will move on. It always does. New crises will arrive. New villains will be named. Epstein will become shorthand, a symbol stripped of texture. But the interview and the files resist that reduction. They insist on something more uncomfortable: that the conditions which allowed him to exist were not aberrations, but habits. If there is value in revisiting this material, it lies in resisting the urge to externalise evil. Epstein was not an alien intrusion. He was cultivated by institutions that prized outcomes over methods, by cultures that mistook access for insight, and by elites who confused proximity with virtue. His story is not a warning about one man. It is a mirror.

Franz Kafka understood that once life becomes performance, sincerity becomes dangerous. Masks protect, but they also suffocate. The Epstein saga shows what happens when a civilisation forgets how to remove them. The disgust now surfacing is not directed only at him. It is the nausea of recognition — the awareness that the distance between what is condemned and what is tolerated was never very wide at all.

The writer is a columnist based in Colombo; views are personal