Martyrs’ Day: Sacrifice, memory, and the moral repair of a nation

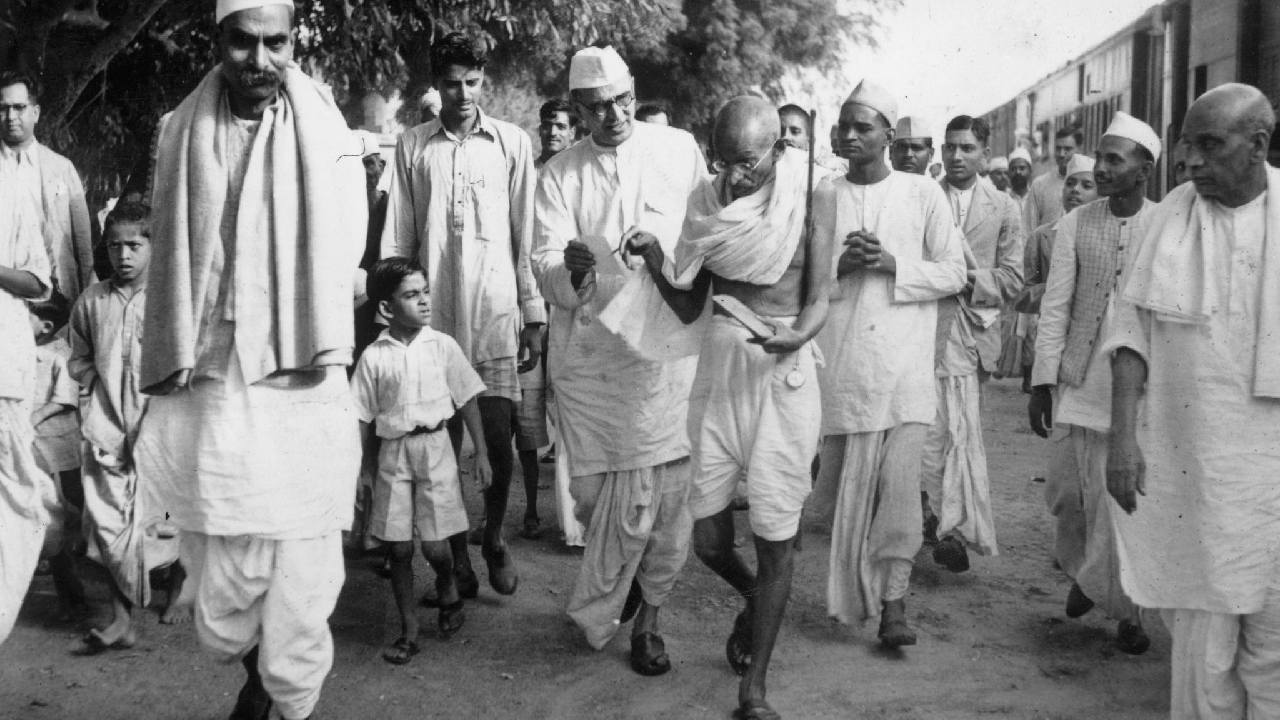

The bullet fired on the evening of January 30, 1948 did not merely end the life of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. It struck a nation already wounded — politically free, yet morally bruised and spiritually exhausted. India had emerged from nearly two centuries of imperial domination only months earlier, but freedom had arrived soaked in blood. Partition displaced more than ten million people; hundreds of thousands were killed or maimed. Women were widowed and violated, children orphaned, families torn apart and scattered like sand slipping through an open palm. The proud were reduced to paupers, entire populations forced into refugee camps and tents, many clustered around Delhi, carrying their lives in bundles and their grief in silence.

Partition was a political reality. For those who endured it, it was surreal. Why had this happened to them? What crime had they committed? Trauma demands explanation; grief seeks a target. Hatred, once ignited and fed, annihilates the moral inheritance of centuries. Poison injected into the veins of a society does not remain contained — it festers, spreads, and seeks new sites of destruction. The thirst for vengeance becomes indistinguishable from the pain that produced it. It was in this moral atmosphere that Gandhi was killed. Some years ago, Ms Surekha Sharma — now an octogenarian and retired principal of a college in Punjab — recounted a memory that continues to unsettle. As a child during Partition, she lived in a refugee camp in Gurdaspur. On the evening of January 30, while children were playing outside their tents, someone came running through the camp with a packet of sweets, announcing news from Delhi. By six o’clock, the radio confirmed it. “We children began dancing,” she said. “Soon, the whole camp gathered. It became an impromptu celebration.” No historical explanation could dislodge that memory. She was unequivocal: that was how it felt; that was what happened.

We know such sentiments existed among the traumatised, but hearing it spoken plainly by someone long known to you brings home a harsher truth. When people are bruised beyond endurance — physically and morally — the mind circles endlessly, seeking meaning for its helplessness. It looks for an act that promises closure. Gandhi’s assassination appeared, to some, as such a release. Yet what Gandhi could not fully achieve in life, he accomplished in death.

As The Guardian observed on January 31, 1948, Gandhi’s death might bring about ‘that change of heart for which he laboured and gave his life’. In India’s moral imagination, sacrifice has long meant the willingness to absorb suffering rather than pass it on. Gandhi embodied that idea. By laying down his life, he drew the poison of hatred into himself and gave the nascent nation a moment to pause, to reflect, and to recover its moral balance. Violence did not vanish overnight, but something essential was arrested. One life may indeed have saved thousands — homes from burning, minds from surrendering permanently to hate. This is the work of martyrdom: not the taking of life, but the offering of one’s own; not destruction, but moral repair. The Isha Upanishad captures this ethic with austere clarity: Tena tyaktena bhunjitha — by renunciation alone does one truly live. At its most luminous moments,

India’s freedom struggle remained anchored in this principle. This tradition of sacrifice was not confined to one path or belief. It spanned philosophies and temperaments. Gandhi practised sacrifice through moral resistance; others chose revolutionary defiance. Yet all shared one truth: freedom demands a price paid in one’s own blood, not that of others.

During the Lahore Conspiracy Case trial, Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt began a hunger strike against the discriminatory treatment of political prisoners. Their comrades debated the move. Jatindranath Das cautioned that once begun, such a strike must be carried through, as breaking it would weaken the cause. He eventually joined, vowing not to end his fast unless the demands were met — something he believed the government would never concede.

Others broke their fast under medical compulsion or at the urging of nationalist leaders. Das did not. During force-feeding, the tube accidentally entered his lungs; his health deteriorated irreversibly. He refused all appeals, even rebuking Bhagat Singh for attempting persuasion. Often, he sang Tagore’s Ekla Chalo Re. After sixty-three days, he died on September 13, 1929.

His funeral procession — from Lahore to Calcutta — became a rolling awakening. Never before had the city witnessed such crowds. In death, he ignited a flame that speeches could not.

A day before his execution, Bhagat Singh received word that an escape could be arranged. He refused. His reply has since become iconic: his name, he said, had become an emblem of the Indian revolution; the ideals and sacrifices of the movement had placed him on a pedestal he could never have reached in life. His only regret was that he had not achieved even a thousandth part of what he wished to do for his country and humanity. He asked that the execution not be delayed. What followed was extraordinary. In death, Bhagat Singh became larger than any living leader. The nation rose as one. His martyrdom continues to nourish the political imagination of generations yet unborn.

Khudiram Bose was barely seventeen when arrested. His associate, Prafulla Chaki, chose death over capture. Initially, no lawyer came forward to defend Khudiram until Kalidas Bose took up his case. Throughout the trial, Khudiram remained cheerful. On the day of his execution, crowds gathered outside the jail. With the Gita in hand, he embraced the gallows, smiling. Witnesses spoke of a radiance that defied explanation. Was he dead — or did he live more intensely in the conscience of his people? Kartar Singh Sarabha was not yet twenty when executed. He had gone to America to study and prosper, but returned to liberate his country. A pillar of the Ghadar movement, his discipline and energy were legendary. When sentenced to death, he thanked the judge. He sang of the hardship of serving the nation, of the countless trials borne by those who choose that path. He could have stayed abroad. He chose otherwise. Madan Lal Dhingra, too, had gone to London for education. There, confronted by colonial domination, he chose sacrifice. Before the court, he accepted responsibility without fear. India, he said, needed to learn how to die; only by dying could one teach it.

There are countless such stories: the dead of Jallianwala Bagh, the victims of martial law, the prisoners of the Cellular Jail in the Andamans — broken in body but unbowed in spirit — and the soldiers of the Azad Hind Fauj. Freedom was not gifted; it was purchased.

Martyrs’ Day is not a ritual of sentiment. It is a summons to memory and responsibility. To remember Gandhi on this day is not to turn him into an icon sealed in reverence, but to recall the discipline he demanded of himself — and of us. He did not offer comfort; he offered responsibility. He lived by the Gita’s injunction that one’s duty lies in action, not in the assurance of results: Karmany evadhikaras te, ma phaleshu kadachana. For him, non-violence was not a tactic but a way of seeing the other, even the adversary, as human. Gandhi warned repeatedly that means are inseparable from ends, that what we do in moments of fear and anger determines the world we will inhabit afterwards. Hatred, once normalised, hollows societies from within. His life was an argument against that erosion; his death, a final reminder of its cost. Martyrs’ Day is not only about the dead, but about the living — the nation we continue to build. To remember Gandhi truly is not to repeat his name, but to ask whether our words, choices and silences still carry the moral weight of the values he lived and died for.

The writer is an author and Historian; views are personal