Malnutrition: Need for a comprehensive policy for the next decade

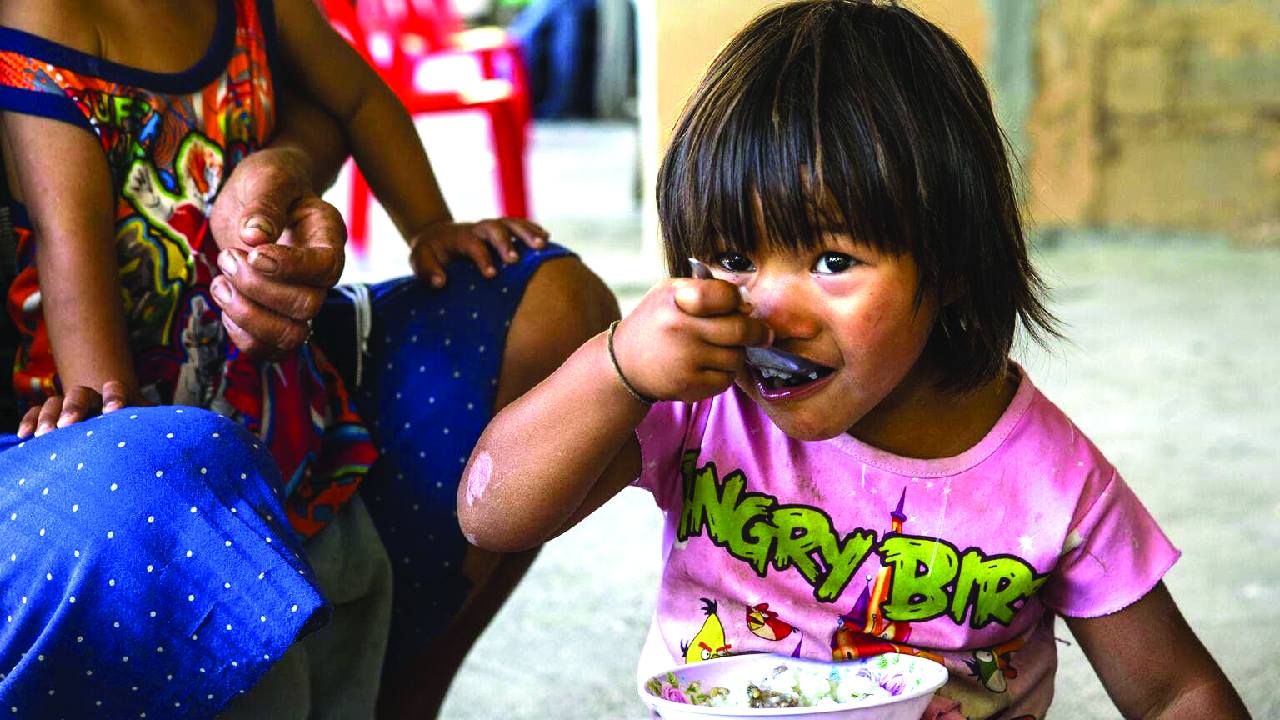

Progress on paper, but a deeper nutritional crisis that India can no longer afford to overlook. India ranks 102 out of 123 countries in the 2025 Global Hunger Index-a stark reminder that the world’s fastest-growing major economy still battles a silent epidemic: child malnutrition. Behind GDP headlines lie millions of children who remain stunted, wasted, or underweight. These are not just health statistics; they signal lost potential, lost productivity, and deepening inequality.

The first 1,000 days: Where the future is won or lost

The first 1,000 days of life-from conception to age two-determine brain development, immunity, and lifelong earning potential. Malnutrition in this window causes irreversible harm. Undernourished children fall sick more often, learn less, earn less, and are more likely to remain trapped in poverty.

The World Bank estimates that every rupee invested in child nutrition yields up to Rs 15 in returns through better education and lifetime earnings. Yet India loses roughly 4per cent of GDP annually to malnutrition-linked productivity losses. While globally about 22per cent of children under five are stunted and 6.7 per cent wasted, India’s burden is far higher-especially among the poor and marginalised.

Progress is real-but too slow and too uneven

Between NFHS-4 (2015-16) and NFHS-5 (2019-21), India recorded modest gains in stunting, wasting, and underweight, reflecting improvements through ICDS, Poshan Abhiyaan, and Swachh Bharat. Public spending on children rose from Rs 69,242 crore in 2017-18 to `1,09,921 crore in 2024-25, while child-health schemes nearly doubled.

Yet the share of the Union Budget devoted to children declined from 3.2 per cent to 2.3 per cent. Education receives the largest share, with nutrition second. In short, spending has increased-but not enough, and not strategically enough. More critically, the flaw is conceptual: our metrics themselves understate the crisis.

Why traditional indicators understate the crisis

For decades, stunting, wasting, and underweight have been measured as separate conditions. In reality, they frequently overlap. A child may be stunted and underweight, wasted and stunted-or suffer all three at once. Yet reporting treats these as isolated problems, never as compounded high-risk cases.

This matters. Children with multiple failures face far higher risks of mortality, illness, cognitive delay, and lifelong poverty than those with a single deficit. But siloed indicators hide them in plain sight. Research shows that once overlaps are accounted for, the true burden of malnutrition is 15-20per cent higher than conventional estimates. India’s crisis, therefore, is not just severe-it is systematically under-measured.

CIAF: A clearer, composite picture

The Composite Index of Anthropometric Failure (CIAF) was developed to correct this blind spot. Instead of tracking isolated failures, it asks a more meaningful question: How many children experience any anthropometric failure, and how many suffer multiple failures simultaneously?

CIAF classifies children into groups with single or overlapping deficits, including the most severe category, children experiencing stunting, wasting, and underweight together. Every category except “no failure” contributes to the CIAF score.

Viewed through this lens, NFHS-5 data tell a very different story. While conventional indicators place malnutrition between 19per cent and 36 per cent, CIAF raises the estimate to 52.4 per cent- a jump of 22-33 percentage points, representing tens of millions of children otherwise invisible to policymakers. CIAF shows a modest national decline since NFHS-4, but also reveals where progress has stalled or reversed-insights siloed indicators fail to capture.

More than a number, CIAF provides a truer map of vulnerability, one India urgently needs for smarter, targeted nutrition policy.

The anatomy of inequality: Who is left behind?

CIAF reveals an uncomfortable truth: malnutrition in India closely tracks inequality. Three patterns stand out in NFHS-5:

1. Rural India shoulders the greatest burden, reflecting weaker service delivery and food insecurity.

2. Risk declines steadily with wealth, with the poorest households facing the highest rates of multiple failures.

3. Maternal education strongly predicts outcomes, with lower schooling linked directly to compounded malnutrition.

CIAF doesn’t just tell us how many are suffering, but who they are-granularity essential for an equity-focused response.

A Tale of Two Indias

State-level CIAF trends reveal sharply diverging trajectories. States such as Haryana, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Arunachal Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu made notable gains through stronger ICDS delivery, maternal nutrition, and food access.

Meanwhile, Nagaland, Lakshadweep, Tripura, Telangana, and Himachal Pradesh saw steep increases. Even Assam, Jammu & Kashmir, and Kerala experienced reversals, underscoring how fragile progress can be amid economic stress or service disruptions.

A third group, including Maharashtra, Gujarat, Goa, Meghalaya, and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, shows stagnation rather than stability. The message is unmistakable: malnutrition in India is spatial, and CIAF offers the sharpest diagnostic yet of where governance must improve.

Policy Implications

A sharper diagnosis demands a sharper response. India’s nutrition strategy must move beyond fragmented indicators to a composite, child-centred lens. This requires governments to:

1. Institutionalise CIAF monitoring at the district level, integrating it into platforms like Poshan Tracker.

2. Prioritise children with multiple failures through intensive packages combining ICDS services, maternal supplementation, and WASH investments.

3. Break intergenerational cycles through fortified school meals, adolescent nutrition programmes, and maternal counselling.

4. Strengthen frontline capacity, training Anganwadi workers to detect and respond to multiple failures early.

5. Develop region-specific nutrition blueprints tailored to poverty, geography, gender, and social marginalisation.

6. Back ambition with resources, aligning fiscal priorities with nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions.

Final Words

Nutrition is not a welfare issue; it is a foundational investment in human capital. A country aspiring to global leadership cannot afford a future where one in three children begins life at a disadvantage.If we act now, guided by a composite, equity-focused lens, we can reverse the trajectory of malnutrition and unlock the full potential of an entire generation. Seeing the whole child is the first step. Designing policy around the whole child must be the next.

Dr. Richa Kothari is an Associate Fellow at the Pahle India Foundation and former Consultant at NITI Aayog. Dr. Payal Seth is a Fellow and Head of Center of Data for Economic Decision-Making, Pahle India Foundation.; views are personal