Learning from the legacy of Public Health of the Indus Civilisation

The Indus Civilisation's hygiene and sanitation standards were millennia ahead of their time and provide valuable knowledge on public health as well as urban planning. Hailed as the "ancient world's most superior plumbing", in some ways it transcended even the plumbing methods that would later be generated by the Roman Empire. Development in sanitation has enabled people to coexist in cities with less risk to their health as compared to the past. Especially, the safe disposal of effluent to prevent the water supply from contamination has indeed proved to be a revolutionary innovation.

The fact that the city of Mohenjodaro alone had about 700 wells speaks volumes about the premium placed on the availability of clean water. This emphasises the fundamental need for access to safe drinking water as a vital aspect of public health. Today, we have the Jal Jeevan Mission, which is a major initiative of the Indian Government to provide clean, sufficient and regular drinking water via individual household tap connections to all rural houses. By making safe water available to village settlements, the women of the house are being freed from the daily inconvenience of walking long distances to fetch water. It entails measures such as rainwater harvesting and grey water management. It is an enterprise that encourages participation of common people through water committees and involves local communities like Gram Panchayats in planning, executing and managing their own water networks. Therefore, the Jal Jeevan Mission empowers communities to supervise their water resources in the long term and is proving to be instrumental in reducing waterborne diseases by ensuring the availability of pure drinking water.

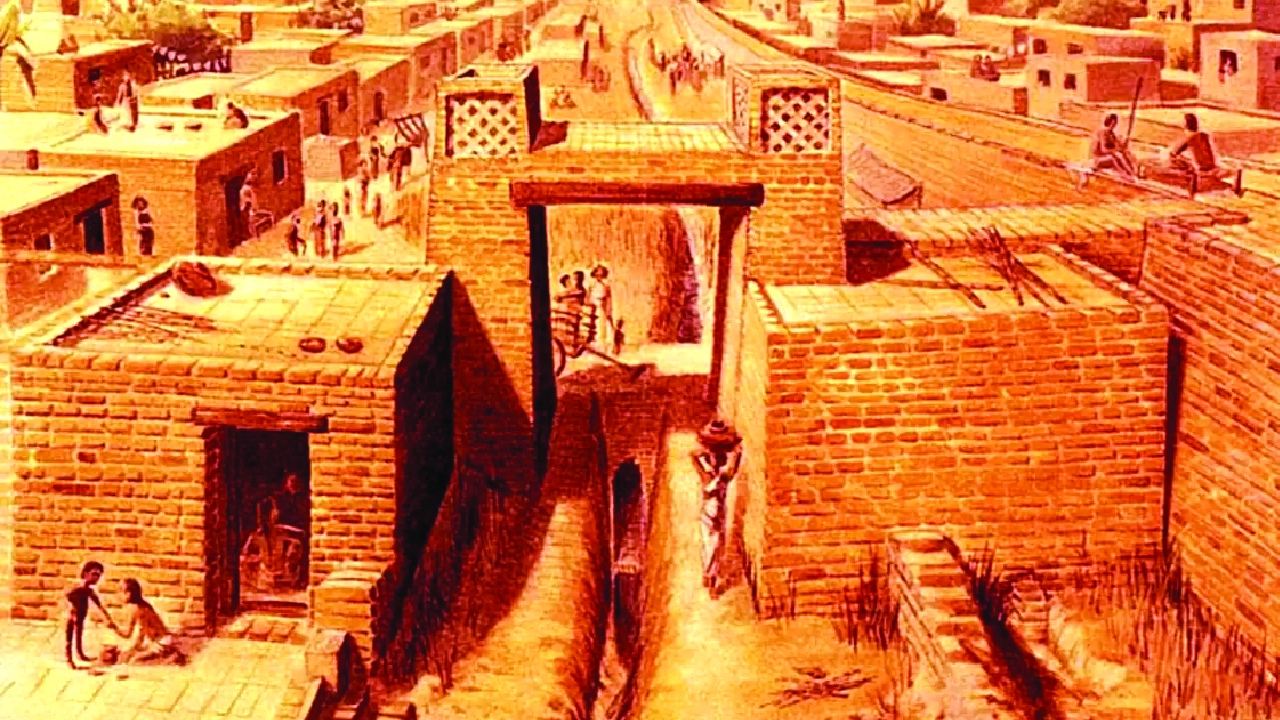

Our ancient history acts as a repository of human experience. It offers profound lessons which would prove highly beneficial for the present. The Indus Civilisation pioneered novel systems of urban sanitation. The meticulous urban planning of the Indus Civilisation is unequivocally one of its most outstanding and remarkable features. The town planning sheds light on the highly developed civic organisations of the city. This sophisticated designing appears to be most impressive in the structural features relating to water supply and waste disposal techniques. Fresh water was supplied by a network of wells. The dirty water and other sewage of almost every unit were transferred into a drain that ran along the street outside. An indoor 'bathing platform' was a common domestic convenience. A distinct outlet in the exterior wall allowed the wastewater to flow into a soak pit or straight into the street drain.

The people of Mohenjodaro were provided clean fresh water exclusively by means of wells, vertically built (or sunken) brick shafts inside the urban area. The wells were made of specially designed, wedge-shaped bricks in order to make room for the smaller inner radius of the cylindrical well shaft. From a technical perspective, the cylindrical well shafts are an engineering marvel as they show that the circular form is statically best equipped to tolerate the lateral pressure bearing on wells 20 m or more deep. These circular brick-lined wells in all probability were the invention of the Harappans. Vertical water supply systems were practically unknown even in the cities of contemporary Egypt or Mesopotamia. It is estimated that Mohenjodaro must have been serviced by around 700 wells, with an average frequency of one in every third house. A water supply network of this magnitude within the city limits was a rarity at this period. A densely populated city like Mohenjodaro could not have been sustained in a semi-arid climate without an independent water supply of its own.

The extravagant water consumption testified by the evidence of bathing platforms in almost every house and the sewer network density prove that the quantity of water utilised by the people at Mohenjodaro was much beyond their personal hygiene needs.

It is also probable that water played a significant part in the consciousness of a community whose agricultural cycle depended solely on the annual flooding of the River Indus. Possibly, the Harappans attributed supernatural powers to the river. The largest building in the city was an imposing elevated public bath. The Great Bath of Mohenjodaro measured approximately 900 square feet, with a maximum depth of around 8 feet. The construction shows evidence of fine brickwork. The pool floor was made of three layers wherein two outer layers of sawn brick set in gypsum mortar had bitumen sealer sandwiched between them. The building of the actual basin is a technical masterpiece which testifies to the extraordinary level of Harappan engineering. The use of bitumen for sealing water-using structures was one of its kind. The Great Bath of Mohenjodaro can be viewed as the most important water-using structure belonging to the Bronze Age. The reputation of the bath house as the city's biggest and most prominent edifice underlines the pivotal cultural value of water and hygiene.

Almost every home in Mohenjodaro had its bathroom located on the street side of the building for the easy disposal of wastewater into the street drains. Ablution spots stood adjacent to the latrines, thus supporting one of the modern principles of hygiene. In instances where baths and latrines were present on the upper floor, they were usually evacuated by vertical terracotta pipes with closely fitting spigot joints, set in the building wall. These ancient terracotta pipes can be understood as the predecessor of our present-day clay spigot-and-socket sewer pipe.

An astounding accomplishment of civil engineering achieved by the Indus culture is the web of pollutant drains built of brick masonry along the roads of Mohenjodaro. These drains had coverings of bricks or wooden planks which could be easily removed for cleaning. A cesspool was installed to prevent clogging in cases where a drain had to cover a longer distance or several drains converged. Apart from the closed sewerage installations for disposing of domestic waste, open soak pits were also commonly used, especially where small lanes opened onto bigger streets. The settled deposits of these pits had to be cleaned periodically. It was not a common phenomenon for the houses to be connected to the sewerage system through individual house drains, as the bathing and toilet amenities were often on the street side of the houses where the wastewater travelled straight down via a chute into the public drain below. The maintenance of the drains must have required adequate manpower.

The model of impeccable Harappan hygiene and sanitation works becomes extremely relevant in contemporary times when we as a nation and world are facing severe challenges relating to water management. For instance, the close proximity of sewer lines and water pipelines poses a constant threat of contamination of water. One needs to look to our past and imbibe the practices that enabled the Harappans to remain healthy and disease-free as early as 3000 BC.Water management directly affects public health by making safe drinking water available, preventing the outbreak of diseases, and assisting sanitation services.

Contaminated water causes illnesses such as typhoid, cholera and dysentery, targeting particularly vulnerable populations. With the rapid increase in population and the creation of new settlements, the way in which the Harappan town's grid layout or urban planning incorporated sanitation from the very outset has a major lesson for us. It highlights the necessity of integrating adequate infrastructure and public health considerations into the basic design of new cities rather than implementing sanitation as a remedial measure.

Another learning that the Harappan instance carries is that sanitation should be a core civic priority cutting across socio-economic divides. Most houses in Mohenjodaro and Harappa, whether humble or elaborate, had access to a bathroom connected to covered drains. This implies that cleanliness or hygiene was not a privilege reserved only for those belonging to the upper echelons of society.

The Indus Civilisation engineered one of the world's most advanced drainage systems. Roads lined with covered brick drains were equipped with inspection chambers for cleaning and upkeep. This reflects the crucial thought that systematic removal of waste is essential to protect public health. Such an insight is extremely pertinent in the context of modern cities grappling with the issue of clogged drains and unmanaged waste. We can learn from this by maintaining and upgrading ageing sewer systems.

The presence of such a complex, consistent infrastructure across the Indus cities hints at a society with people who shared a strong sense of belonging and civic responsibility and were committed to actively contributing to the well-being of the community as a whole. The entire sanitation framework seems to have rested on a cooperative civic organisation. It hints at the key role that the people of the Indus Civilisation must have played in maintaining the sanitation works.

The Swachh Bharat Mission emphasises that it is every citizen's social responsibility to contribute to a clean environment. This involves proper management of household waste. We must never dump materials that obstruct drains. We should strive to incorporate the above-mentioned features of the Indus Civilisation relating to proper waste management, meticulous urban planning, robust sanitation infrastructure, and the availability of pure drinking water in our city spaces. By doing so, Indian citizens will be making efforts to continue the legacy of the Indus Civilisation. Let us all, with unflinching resolve, work towards a Swachh Bharat.

The writer is a Senior Research Fellow, Bharat Ki Soch ; views are personal