Indian Scholars Decode Dutch Records to Rewrite Kerala’s Colonial Past

Four students from India headed for the Netherlands under an agreement signed between the two countries to discover unexplored colonial history in the depths of an untouched archive.

Cosmos Malabaricus, the Indo-Dutch project that the young students were entrusted with, was expected to rewrite the medieval history of the then Malabar region, providing rare insights into why the Kerala model of development experience was different from the rest of India and even the rest of the world.

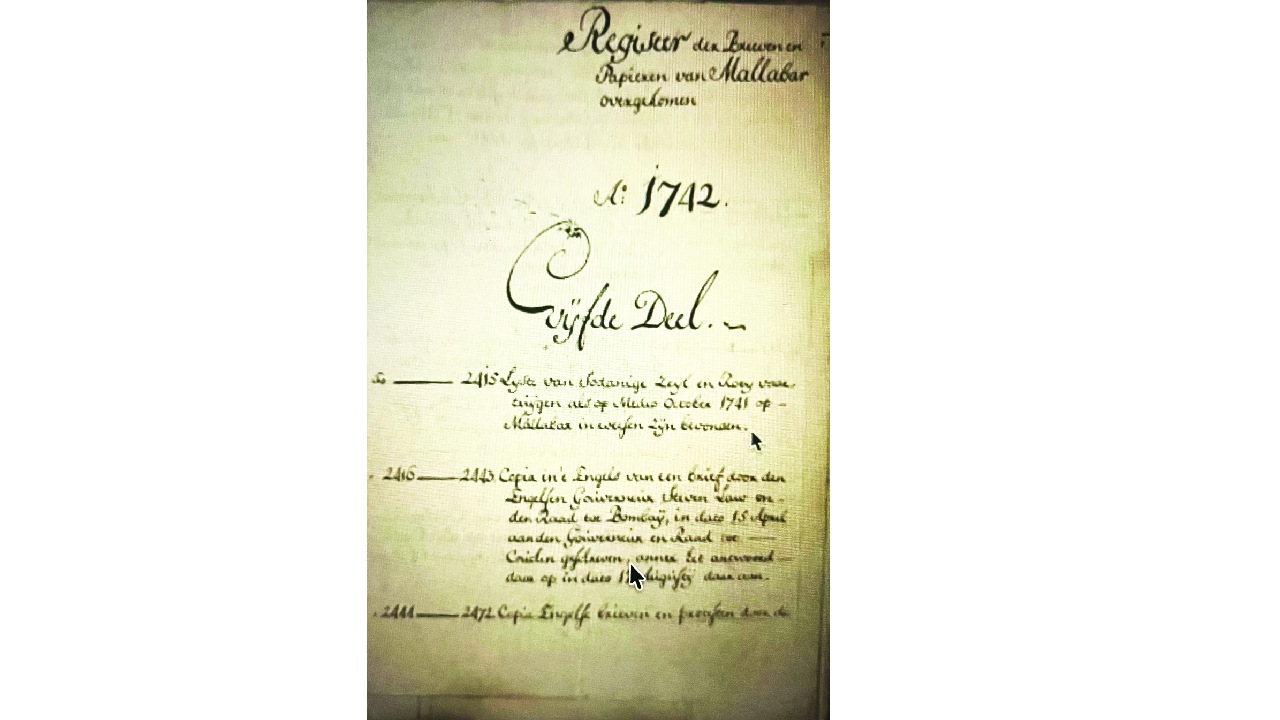

Nearly two years later, fascinating tales from 1650 AD to 1800 AD, when present-day Kerala was under Dutch rule, have emerged from painstaking research by the Indian students who pored over tens of thousands of manuscripts from the period written in the old Dutch language.

“Four students from Kerala came to the Netherlands for studies. They learned old Dutch and were in an internship at the National Archives of the Netherlands. They had a very intensive course,” says Jos Gommans, the Dutch historian behind the Cosmos Malabaricus project, named after Hortus Malabaricus, a botanical treatise of the Malabar coastal region by the 17th century Dutch Governor Hendrik van Rheede.

Neglected history

"The Dutch archive on Asia, especially on Kerala, is extremely rich, but it has been neglected for a very long time," explains Gommans, a Professor of Colonial and Global History at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who is a prominent speaker at the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF), beginning on January 15. The India-Dutch academic collaboration, which received the nod of the Ministry of External Affairs, is the result of a Memorandum of Understanding signed between the Kerala Council for Historical Research and the 1575-founded Leiden University and the Hague-based National Archives of the Netherlands three years ago.

Among the many discoveries made by the Indian students is how the Mukuva community, a fisher people’s community in Kerala, was protected by the Dutch rulers. But the highlight of the studies is the story of a much-neglected Dutch translator who collected stories about Kerala’s myths and history.

“So far, nobody has looked at this person, Van Meeckeren, a Dutch company employee and a diplomat who was one of the translators who served in Kerala for several decades and had a finger in every dish, almost,” says Gommans, the author of several books on the cultural and intellectual exchanges between Europe and India. “Meeckeren’s father was a Dutchman and probably his mother was from Kerala,” he adds.

“Meeckeren was very much aware of what’s going on. He also had this historical interest. So it was a really, very important figure that nobody knows about. He wrote a survey of Kerala history, and all that in the early 18th century. So I think he’s really the kind of somebody we discovered in the archives, I have to say,” adds Gommans, who has written extensively on Dutch colonial history, including the co-edited Exploring the Dutch Empire and co-authored The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600-1800.

Gommans' latest book, Sun, Emperor and Pope: Neoplatonic Solar Worship in Mughal India and Barberini Rome, will be released at JLF. "Meeckeren’s records are a massive source of history," says Gommans, who headed several programmes at Leiden University in the past two-and-a-half decades to equip over 150 students from Asia and South Africa with the skills to work with Dutch colonial archives, fostering a deeper integration of these sources into the regional histories of Asia and Africa.

Micro-level records

The Dutch, who defeated the ruling Portuguese in 1658, dominated the Malabar region before they were in turn defeated by the British. The Dutch empire in Asia, which was headquartered in Jakarta, Indonesia, spanned a vast geography, from Basra in Iraq to Deshima in Japan. Observant administrators of the Dutch East India Company kept daily records of economy, trade, judiciary and even places of worship up to the village-level.

While some Dutch records exist within India, most of the manuscripts of Dutch administrators were taken to the Netherlands, which are now housed in the National Archives in the Hague. “The Dutch records of Malabar are 100 metres long,” says Gommans about the digitised manuscripts that contain little-known aspects of Malabar’s history.

“The Dutch had a very deep interest in knowing what’s going on, whether in a temple, who is the patron in what temple, what kind of political rivalry is going on in the patronage of a temple. So that all that information is in the Dutch archive," says Gommans, whose published works include two monographs on early modern South Asian history---The Rise of the Indo-Afghan Empire, 1710-1780 and Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and High Roads to Empire.

"I think there is a real gap, let’s say, for the Dutch period," explains Gommans. "That’s because the archive is in Dutch language and not many people know the Dutch language. So we have a period that is fairly well covered in the Portuguese period. Then we go into the 19th century, the early modern period, in which all these flourishing regional communities simply continue to exist, but we don’t know what happened," he adds.

“The Dutch were really very much involved in various courts in Kerala. So they wrote very detailed reports about what was going on at these courts. The English period is better covered because of the access that people have to the English archive, because of the language and all these gazettes.

The Dutch really have a huge gap. So, I think to go from the Portuguese to the English, that is the challenge, and therefore, you need the Dutch period materials,” says Gommans.

The Indian students, who joined Leiden University for a Master’s programme in Colonial and Global History and learning medieval Dutch, will complete their studies next week. “I think the project is over,” says Gommans. “We don’t have any funding anymore. We were already quite lucky with getting funding. It’s partly funded by the Dutch government and partly by the Kerala government,” he adds.

The writer is a senior journalist with a focus on contemporary history, culture, and the arts.; views are personal