How could rare earth scarcity push India into a China trap?

India’s march towards becoming a technology superpower in the domains of electric vehicles, defence systems, energy grids, space and science critically depends on rare metals which most people have never heard of. These are the 17 rare earth elements that make or mar any country’s achievements in the technology sector.

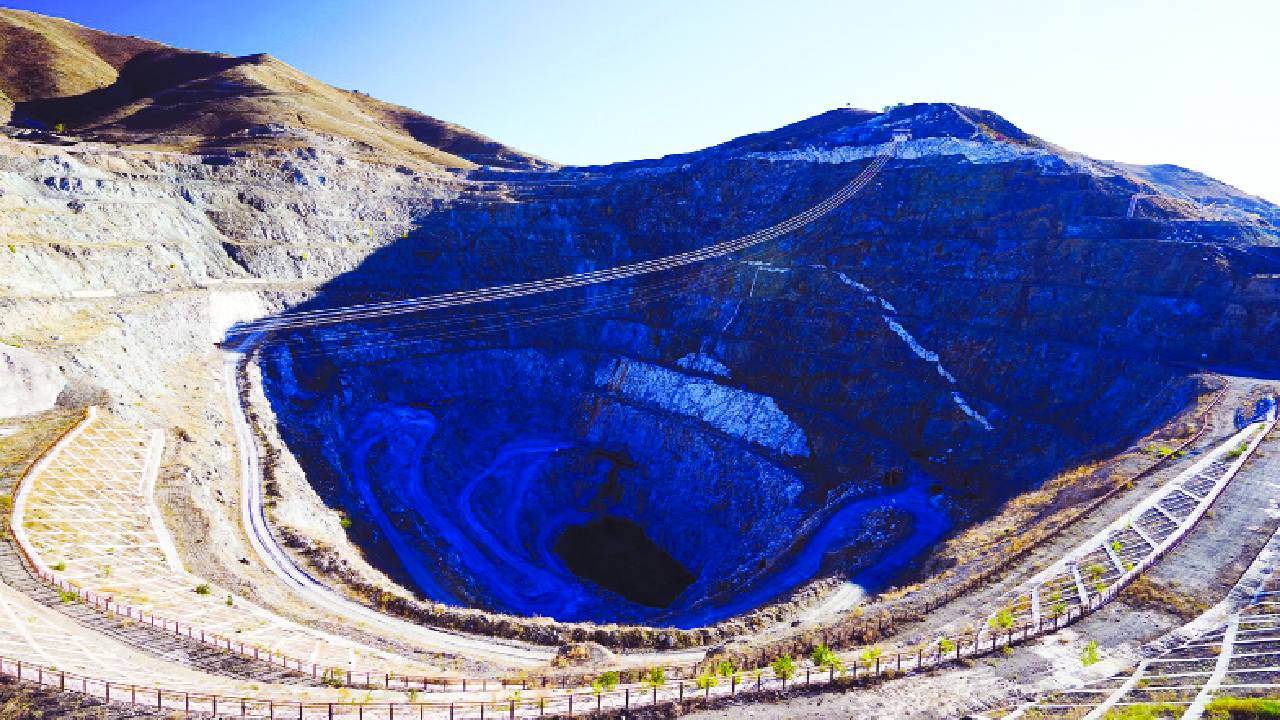

India is not short of them. From Odisha’s beach sands to the coastal stretches of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, the country holds around 6 to 7 per cent of the world’s rare earth reserves. Yet it contributes barely 2 per cent of global output. The problem is not below the soil, but above it — the near absence of policy, foresight, and perhaps the inability to match China’s mining and exploration economics.

China controls nearly two-thirds of the world’s production and almost 90 per cent of its refining facilities. Even ores mined in the US or Australia are often sent to China for processing. This dominance gives Beijing quiet but immense leverage - the ability to decide who gets to build the next generation of technology.

India’s monazite-rich sands are managed largely by Indian Rare Earths Limited (IREL) under the Department of Atomic Energy, but for decades private mining was restricted due to nuclear sensitivity concerns. While China built a massive ecosystem of mines, magnets and finished electronics, India kept its resources idle or exported raw sand.

The result is a form of strategic dependence that undermines India’s technological sovereignty. Without rare earths, no electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, advanced radars, or smartphones can exist.

China’s rare earth offer to India unsettles Washington

India’s recent drive towards rare earth self-reliance has gathered quiet momentum. The government has rolled out new incentives to attract domestic refining and magnet manufacturing, while strengthening the Indian Rare Earths Limited network to handle processing locally.

This shift comes as China, the world’s dominant rare earth supplier, has made a calculated move — offering to resume limited supplies to India on the condition that the materials are not re-exported to any third country. The unspoken reference is to the United States, which has been struggling to secure its own non-Chinese supply chains.

China’s conditional offer to India emerged just as US officials were pressing allies to diversify rare earth sourcing away from Chinese control. Beijing’s signal that India could buy only for its own consumption — not as a back door for American industries — most likely angered Trump, who imposed even higher tariffs on China. What began as a trade war over steel and semiconductors has thus extended into a strategic contest over the raw minerals that underpin modern technology. India is now caught between opportunity and caution, wary of being drawn into the rivalries of its two biggest trading partners.

India’s problem is not geological scarcity but the lack of refining and processing capability. Even if India mined aggressively, the ores would still have to be sent abroad for separation — mostly to China. That is where the true choke point lies.

To break out, India needs a national rare earth mission: open mining to private investment under strict safeguards, establish domestic refining clusters, and link universities and defence laboratories for downstream innovation. Until India can turn its rare sands into strategic strength, it will continue to build on borrowed elements.

The writer is an expert in science, research and development; views are personal