From labour reform to EoDB 2.0: The structural shift India needs for growth

India’s decision to implement the long-pending labour codes deserves appreciation. For decades, the country’s entrepreneurs have operated under a maze of 29 overlapping and often contradictory labour laws. Consolidating them into four streamlined labour codes is more than an administrative exercise; it is a long-awaited structural reform that simplifies compliance, increases the probability of enforcement, and creates a more predictable environment for doing business. A simpler legal framework is always easier to follow and easier for the state to enforce, making this a foundational step towards improving India’s ease of doing business.

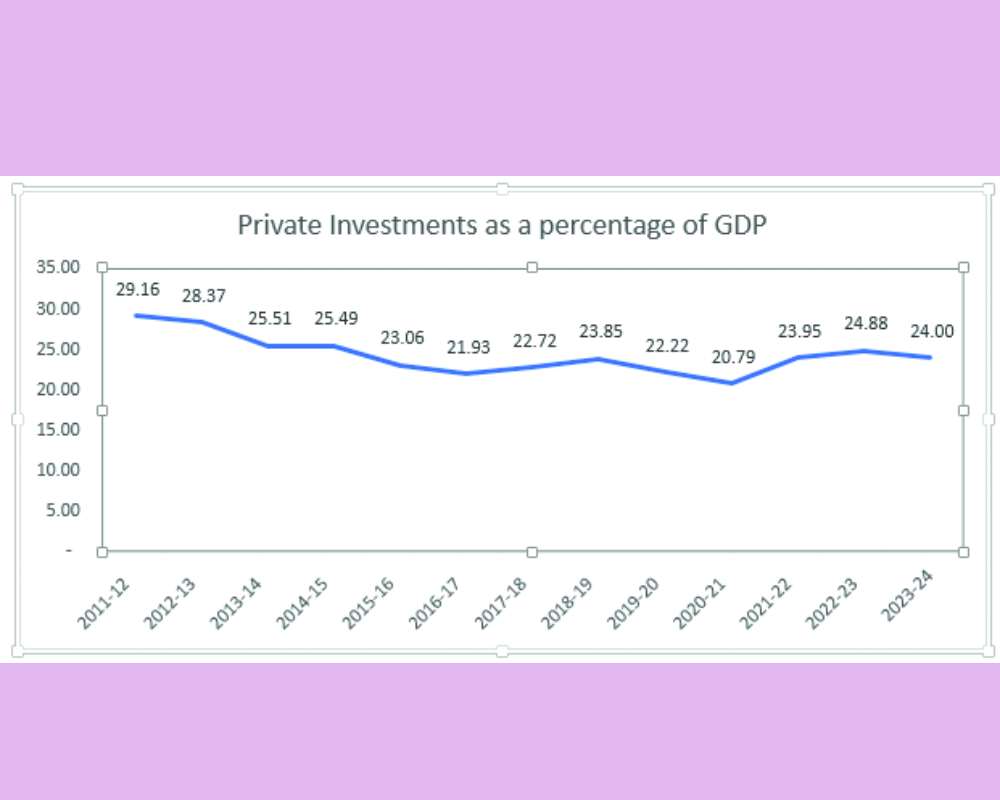

Falling Private Investments in India

This reform also comes at a critical time. Private consumption today accounts for almost 60 per cent of India’s GDP, but investment — particularly private investment — remains much lower and has not recovered to the levels needed to drive a sustained growth cycle. Private investment as a share of GDP has declined over the past decade.

Investments Flowing Abroad

The picture becomes even clearer when one looks at foreign investment flows. Net FDI (FDI inflows minus outflows) has been falling, driven by both decreasing inflows and rising outflows. This trend implies that even Indian firms are increasingly choosing to invest abroad rather than expand domestically. Why is that so? Domestic regulatory conditions appear to be the most important determinant of these investment decisions.

Why Macroeconomic Policy Has Failed

Importantly, this decline in investment cannot be attributed to weaknesses in macroeconomic policy. Fiscal policy has been supportive: corporate tax rates were reduced, GST rates have been rationalised, and taxpayers earning up to Rs12 lakh annually have received relief. This has led corporate profits to reach all-time highs in recent years.

Monetary policy has been accommodative for years, ensuring liquidity and low borrowing costs. But these tools have mainly boosted consumption, not private investment. Investment responds more to regulatory clarity, reduction in compliance burdens, and predictability in doing business. This is why the labour codes represent a step in the right direction but only the first step. If India wants to revive private investment and unlock the next cycle of high growth, it must go further.

What is Needed

Deregulation, decriminalisation of minor business offences, and a decisive reduction in regulatory complexity are essential. Entrepreneurs should be spending their energy building businesses, creating jobs, innovating, and scaling — not navigating compliance paperwork.

Simplifying the regulatory architecture and focusing on strong enforcement of a smaller number of well-designed laws will not only increase compliance but also stimulate entrepreneurial drive. It will encourage firms to expand operations, take risks, and invest in capacity without fearing excessive compliance burdens. These reforms directly contribute to competitiveness and, more importantly, to investor confidence.

EoDB 2.0

Crucially, the next wave of reforms must come from the states. The Economic Survey 2024–25 explicitly argues that the next phase of ease of doing business (“EoDB 2.0”) must be led by state governments. A significant portion of the compliance burden — including inspections, approvals, certifications, and procedural requirements — originates at the state level.

The Survey also recommends a three-step process for states to systematically review regulations for their cost-effectiveness.

The steps include:

1. Identifying areas for deregulation,

2.Thoughtfully comparing regulations with those of other states and countries, and

3. Estimating the cost of each regulation on individual enterprises.

If India is to truly raise its investment rate, states must adopt a philosophy of regulatory pruning by retaining only those laws that support industrial growth and removing those that hinder it. Such pruning would require wide stakeholder discussions, but the benefits would far outweigh the costs.

These are precisely the types of changes repeatedly described as structural reforms — reforms that change the rules of the game, not just the fiscal or monetary signals within the existing system. Structural reforms reshape incentives, reduce friction, and create a business ecosystem where both domestic and foreign investors feel confident about making long-term commitments. Viksit Bharat 2047 will require private players to lead the way while the government acts as an enabler and facilitator.

Rajiv Kumar, former NITI Aayog Vice-Chairman and Chairman of the Pahlé India Foundation, is a prominent economist focused on economic reforms. Samriddhi Prakash is a Research Associate at the Pahlé India Foundation; views are personal