After the beginning of post-Independence anti-Hindu violence in J&K, Patel was the only solid politician who helped conjoin it to India

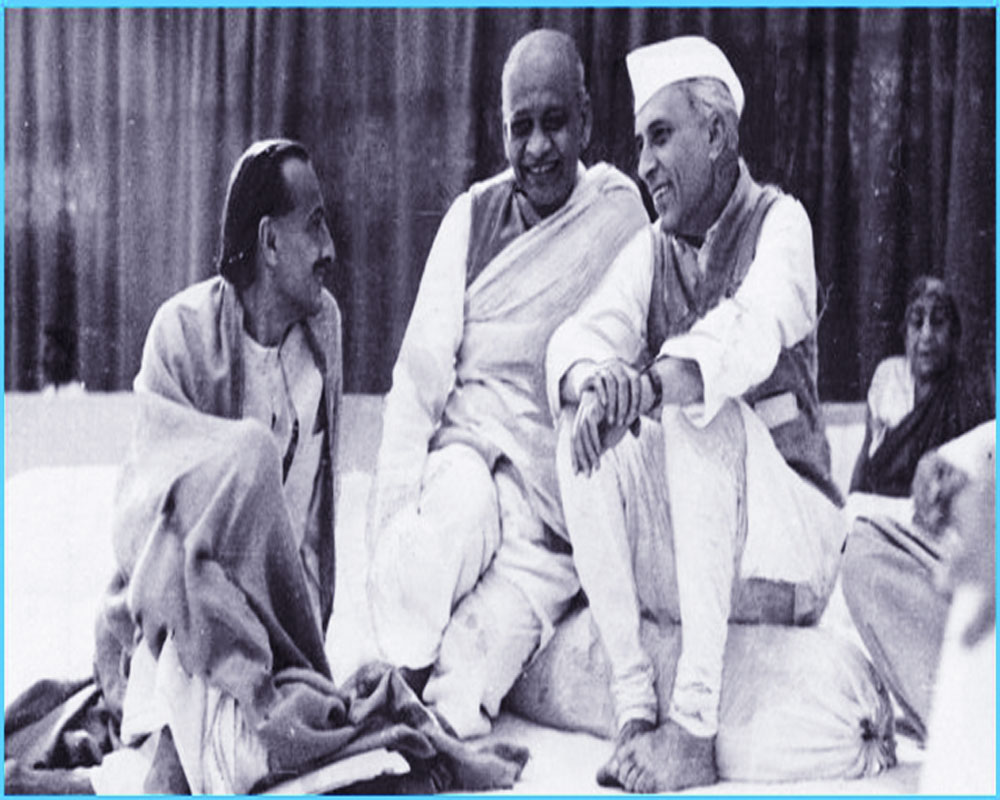

Now that the abrogation of Article 370 is a settled thing, it would perhaps be appropriate to reveal how Kashmir came to India rather than going to Pakistan. The version of what happened step-by-step between Maharaja Hari Singh, the then princely ruler of the State of Jammu & Kashmir, and the then Indian leadership is largely known. It is, however, prejudiced to some extent as attempts have been made to give all credit to Jawaharlal Nehru and keep Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel out, so that Patel does not walk away with all the credit for integrating the princely states at the cost of Nehru.

Distinguished historian and columnist Patrick French in his book Liberty or Death has revealed what common sense applied to the limitations of the 1940s could have made possible. Maharaja Hari Singh was generally considered a progressive ruler, though the scope of his political reforms was limited. Patrick French writes that during the weeks leading up to Independence, India’s last Viceroy Mountbatten had tried to persuade the Maharaja to decide about Kashmir’s future, which the latter refused to discuss seriously. Ostensibly, the Maharaja’s deferment of a decision on what to do after the British had left stemmed from his firm conviction — voiced to his son yuvraj Karan Singh as late as July 1947 — that the British were never really going to leave India.

Events, however, overtook the Maharaja and his State. Come August 15, 1947, and Hari Singh faced a hostile dispensation. The leader of the pro-Congress All Jammu and Kashmir National Conference, Sheikh Abdullah, had close links with Nehru, whose hostility towards Hari Singh was no secret. A revolt had begun in the southwest of the State in Poonch, which had always historically been antagonistic towards the Maharaja’s rule. Muslim farm workers there rose against their Dogra landlords, killing some local Hindus and driving others from their homes. This was the beginning of post-Independence anti-Hindu violence in J&K. Maharaja Hari Singh slowly began to incline towards India. He realised that his State would be destroyed if he joined Pakistan.

By mid-October 1947, Kashmir had been thrown into a serious crisis. The uprising in Poonch was joined by Pakistani armed brigands, with official encouragement from the Pakistani regime. However, it now comes to light that India wasn’t oblivious of the looming threat. For several weeks, Delhi had been secretly supplying weapons and ammunition to the State’s armed forces and making preparations for a military advance. The tipping point came with the armed invasion of several thousand Pathan tribesmen. On October 22, accompanied by a few hundred Poonchis, a ragtag army began to proceed towards Srinagar. The Pathan raiders were acting on Pakistan’s direct orders, though Pakistan denied any complicity in it. On reaching Baramulla, Uri, Pattan and Muzaffarabad, the raiders murdered, raped and looted anybody and anything they could lay their hands on. British nuns of Franciscan convent at Baramulla too were not spared.

While Hari Singh’s royal dynasty despaired of having lost Kashmir, India would not. The Government of newly independent India set about recovering the territory. Mountbatten reportedly was convinced of the righteousness of India’s case. He told Patel that he had heard from a British officer, who had heard from another British officer, that the invading Pathans were “very definitely organised”. A fortnight later, Mountbatten wrote to King George VI: “It was unquestionable that, if Srinagar was to be saved from pillage by invading tribesmen, and if the couple of hundred British residents in Kashmir were not to be massacred, Indian troops would have to do the job… I therefore made it my business to override all the difficulties which the Commanders-in- Chief, in the course of their duty, raised to the proposal.” Thus, the indispensability of India’s role in saving Kashmir was acknowledged at the outset.

But a military thrust into a territory which in those days was accessible only with difficulty required weeks, and possibly months of planning. It was only some time later that Viceroy Mountbatten realised the extent of preparations that must have been made by India, the credit for which goes to Patel. It appears Patel had kept Nehru in the dark about procedural details.

An Indian Army officer present at a meeting of the Defence Committee in New Delhi later that day said Nehru still had doubts about intervention and “talked about the United Nations, Russia, Africa, Godalmighty, everybody, until Sardar Patel lost his temper. He said, ‘Jawaharlal, do you want Kashmir, or do you want to give it away?’ Nehru said, ‘Of course, I want Kashmir’... and before he could say anything, Sardar Patel turned to me and said, ‘You have got your orders’.”

The Indian Army drove out the Pakistani Pathan raiders, chasing them all the way to Mirpur. India was militarily well-positioned to recapture the entire State but Nehru, concerned more about his image internationally, erred grievously in taking the matter to the UN, which imposed a stalemate that plagued India for seven decades. With Article 370 having been laid to rest by the Modi administration, it is time to recognise Patel’s role in saving Kashmir for India.

(The writer is a well-known columnist, an author and a former member of the Rajya Sabha. The views expressed are personal.)