India has many architectural and cultural marvels, centuries and sometimes millennia old, that are not so well known or frequently visited

The buildings and monuments of past centuries, carefully preserved, are one of the most important and visible aspects of a people’s history and their cultural legacy, that constantly makes them aware of their past and gives them a sense of identity and meaning that cannot be falsified. Many of India’s ancient monuments are famous and visited by many; some of them are even inscribed on the World Heritage List of UNESCO. But there are many, many more of such architectural and cultural marvels, centuries and sometimes millennia old, that are not so well known or frequently visited by people, apart from those belonging to the rarefied circles of historians, scholars and archeologists.

The relatively lesser-known archeological sites - a Sankisa in Uttar Pradesh, a Kesariya in Bihar or a Krishnagiri Fort in Tamil Nadu - have always fascinated me more and I have found myself compelled to explore them, to walk on the roads less travelled.

Last month, I had the opportunity to visit the Udayagiri caves of Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh. It is an ancient city of the Mauryan times to which the queen of Emperor Ashoka belonged. Today, as one walks on the narrow streets and lanes of Vidisha to reach the Udayagiri rock cut cave temples, one can only imagine what splendours it would have held in those times, situated as it was on the crossroads of important trade routes. Ashoka was still not on the throne of Magadha and was still the prince-governor at Ujjain — another ancient city.

Vidisha’s Udayagiri hill cave temples were of the Gupta period and mainly of Vaishnava inspiration. To the left of the main street, scattered over low hills, lay many rock-hewn caves, most of them temples once, showing ancient statues and busts of gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon - Vishnu, Shiva, Kartikeya, etc. Aboard of the Archeological Survey of Indiain forms that it was during the reign of Emperor Chandragupta II of the Gupta dynasty, known in legend as Vikramaditya, that these temples were built and carved and that one of his ministers had visited the site.

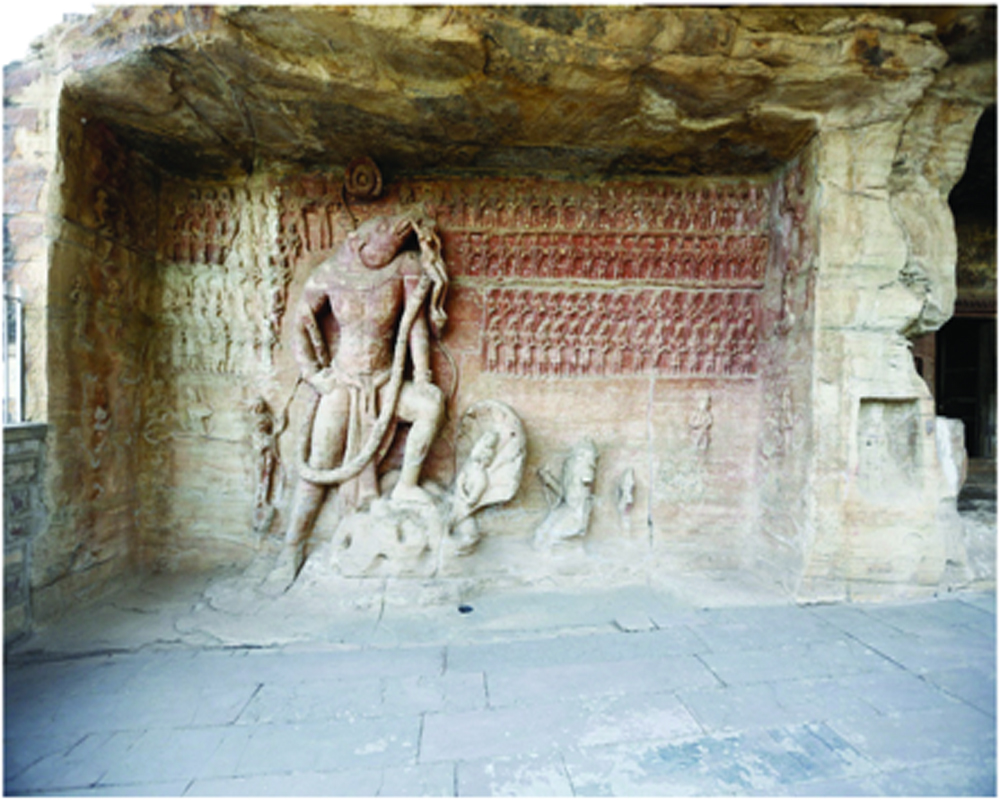

To my naïve eyes, the most beautiful piece of carving was that of Lord Vishnu in his famous Varaha Avatar (the incarnation of a boar), holding up mother earth, shown here as a woman rather than a sphere, on his tusks. It is a beautifully and wonderfully detailed piece of art carved on a rock face, and shows apart from the principal characters, beautiful carvings of goddess Ganga on her crocodile and goddess Yamuna on her Tortoise, among many others. Another exquisite and massive piece of sculpture was that of Lord Vishnu lying down on Sheshnaga.

The Heliodorus column that stands a couple of kilometers away from the hills and was erected some two thousand years ago by a Greek Ambassador in the honour of a Hindu god —Vasudeva — itself is a testimony not only to the antiquity and importance of this ancient land, to the connection across modern boundaries and civilisations and to the height of metal craft in those ancient days but also to the fact that in those ancient times the world was so much interconnected and that the acceptance of ‘ótherness’ - the other’s way of living, thinking, their beliefs and faiths and even of their gods, was so prevalent that a Greek ambassador was putting up a huge pillar in honour of a god belonging to India.

I left Udayagiri hills and Vidisha and travelled back to Delhi but those ancient carvings and sculptures and the stories and legends depicted in them never quite left me so I was almost shocked when only a few days later, as I was climbing up the stairs of the India International Centre in Delhi, to attend a book launch, I came face to face with a huge black and white photograph of exactly the same sculpture of Varaha Avatar of Udayagiri hills with Lord Vishnu carrying mother earth on his tusks. It was too much of a startling coincidence and stunned me for a while.

As I continued on my way, there was a strange feeling of oneness in me. It was as if we were all bound together as one across centuries with those forgotten artists who had chiseled out that great pieces of art, with the kings and ministers who had financed it, with those countless devotees who would have worshipped at the feet of their god, to the archeologists who would have, centuries later, diligently preserved and conserved them for antiquity.

(The writer is a senior IAS officer, posted in Delhi as Additional Secretary, Ministry of Culture, Government of India. The views expressed are personal.)