One of the best-known figures from Madhubani, Gauri Mishra questioned and challenged the orthodoxies and worked relentlessly for women’s empowerment, says Sujata Prasad

Exhuming the legacy of someone as extraordinary as Gauri Mishra is not easy. Her demise on August 17 has been entirely overlooked. It is not easy to explain this amnesia or indifference. One of the best-known figures in Madhubani, Bihar, she had a fearless and an indomitable approach towards supporting impoverished women. She took upon herself to question orthodoxies of every kind and was the go-to person for every woman battered by violence.

One of the strongest voices against regressive gender politics of the ‘80s and the ‘90s, she was part of an upswell of activism against gender violence and sexism. Her freedom of thought and invincible spirit was infectious. Posted in Bihar during that time as the head of women’s empowerment programme, Development of Women and Children in Rural Areas (DWCRA), I found myself visiting her karmabhoomi, Madhubani, repeatedly for a quick dose of inspiration.

Born in 1933, Gauri married Dr Bhavanath Mishra of the Darbhanga Medical Hospital when she was a teenager and studied for a few years in England. She started her work life as an academic interested in gender issues. In 1974, the Committee on Status of Women presented its watershed report Towards Equality, that confirmed the worst fear of sceptics. The report combined with nationwide protests on the custodial Mathura rape case and an avalanche of dowry deaths, resulted in the emergence of several tightly-knit women’s organisations.

Gauri’s direct involvement in women’s issues started in the ‘70s, when she began assisting German anthropologist and folklorist Erika Moser and American Fulbright Scholar Raymond Lee Owens in their research on the Mithila art. She began working on the historiography of the art, exploring its social dimensions and tracing the antiquity of some of the artforms to the Brahma Purana.

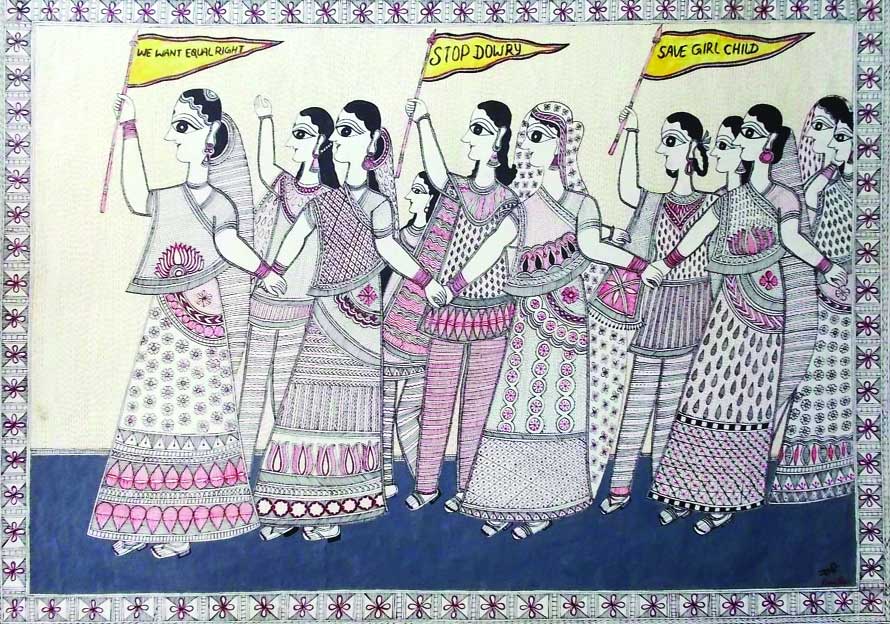

By 1977, women artists from the area became her prime focus. She founded the Master Craftsmen’s Association of Mithila in partnership with Owens to put an end to the exploitation of impoverished, struggling artists by middle-men. The association provided a platform to eminent women artists like Jagdamba Devi, Sita Devi, Ganga Devi, Maha Sundari Devi, Bauwa Devi, Yamuna Devi, Shanti Devi, Chano Devi, Lalita Devi, Shashikala Devi, Leela Devi, sikki artist Bindeshwari Devi, paper-mache artist Chandrakala Devi and sujani artist Karpoori Devi. It encouraged them to combat the patriarchal gaze with their artwork. Young artists like Rani Jha were encouraged to introduce avant garde feminist themes in their pictorial vocabulary.

By the ‘80s, she teamed up with activist Viji Srinivasan to give a new visibility, potency and legitimacy to women’s struggle. Patterned on Ela Bhatt’s SEWA, the SEWA Mithila was launched in 1983. Gauri also founded the Nirbhaya Ashram, a shelter for widows and homeless women. She helped them to deal with their heartbreaks by involving them in her crusade for social justice and change, a crusade that was much bigger than their own personal stories. She was deeply influenced by the Bodhgaya land struggle, where women’s quest for independent rights in land had received traction. Viji was with the Ford Foundation from 1980-86, and then with Oxfam America before founding her own organisation in Bihar. She supported Gauri in setting up economically viable craft and animal husbandry projects. The NGOisation of women’s issues may have resulted in certain serious concerns, but no one could doubt that Viji and Gauri were leading genuine movements for gender rights and justice in Bihar.

Our work with grassroots women brought us together. We fought for women’s right to livelihood and their independent rights in land and water assets. We created radical new templates and toolboxes. Giving up hope was not an option. I joined their protest marches and listened to their fiery oratory against dowry and female foeticide at the Saurath Sabha (where Maithil Brahmins traditionally assembled to negotiate marriage) and other forums. I can’t but be nostalgic about our collective joy when a government owned pond was leased to a woman’s group in Raiyyam. I am equally nostalgic about our schmaltzy moments together, when at the end of a day spent travelling through villages, we would eat our rice and fish meal in the moonlight on a charpoy, surrounded by radiant women from Gauri’s ashram, our night sound tracked by romantic songs of the celebrated Vaishnava poet Vidyapati. I began to see myself less as a civil servant and more as an activist.

Viji’s death in 2005 affected Gauri Mishra deeply. For some time, she leaned on her son Samarendra who joined SEWA as a project coordinator. His death in 2011 devasted her completely. She failed to take charge of her life, abandoned whatever was left of her work and retreated to her family home in Darbhanga. Her work needs to be recognised, especially at a time when India has one of the lowest female labour force participation rate in the world and is nearly at the bottom of the Gender Development Index and Gender Inequality Index.

(The writer is a former civil servant and an art columnist.)