The artiste mainstreamed rural, tribal, folk art and craft by bridging the chasm between the elite and the sub-altern tribal forms. By Sujata Prasad

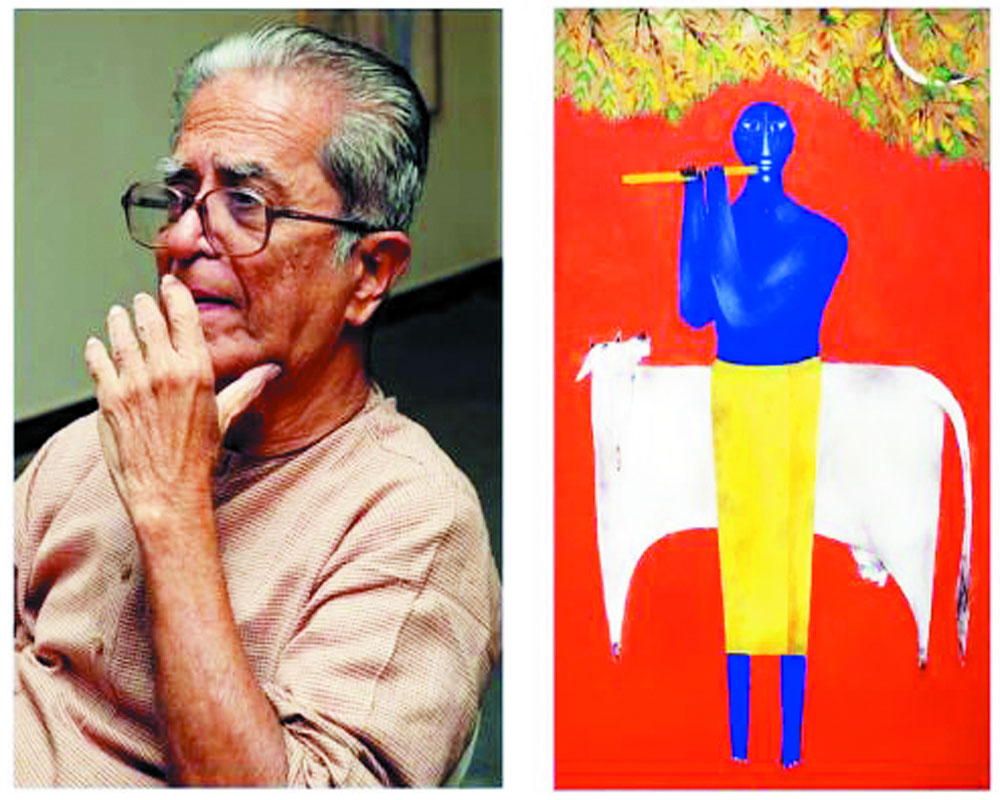

Haman-hai-ishq — love is all there is — words evocative of India’s rich pluralistic tradition represented the quintessence of what Haku Shah, a celebrated Gandhian artist and social anthropologist of exceptional vision, stood for. His death at the age of 84, after a long illness on March 21, didn’t go unnoticed. The National Gallery of Modern Art celebrated his extraordinary life by hosting an evening of music and intimate reminiscences.

An avant-garde in more ways than one, Shah mainstreamed rural, tribal, folk art and craft by bridging the chasm between elitism and art that has often been relegated to the eponymous category of folk or subaltern tribal expressions. His love for folk artists and artisans evolved as part of a burgeoning movement in the 50s for the creative intersection of craft and design. One of his first assignments was at the Weavers’ Service Centre established by Pupul Jayakar near the Opera House in Mumbai. An astonishing number of artists with different terms of engagement gravitated to the centres and elsewhere — Prabhakar Barwe, Jeram Patel, Jogen Chowdhury, Himmat Shah, Gautam Vaghela, Bhasker Kulkarni, Amrut Patel and Manu Parekh to name but just a few. Also budding scenographers like Rajeev Sethi and Martand Singh. KG Subramanyan came occasionally and created stunning standalone sculptures from the fibres of handspun wool. Haku Shah thrived in this hothouse of creativity. His next assignment, a long stint with the National Institute of Design, was also not an act of artistic hubris, but was driven by the need to research tribal art and crafts, rituals and belief systems that had intrigued him for a long time. In 1978 he was appointed advisor to the Mingei International Museum at San Diego in California .

Shah’s exquisite personal collection of terracotta objects picked up from villages near Valod, Mandvi, Buhari, Poshina and Chhota Udaipur in Gujarat and the tribal areas of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka was the seedbed of a series of revelatory and beautifully curated exhibitions, beginning with a modest display in Sevagram in 1955. His travelling terracotta exhibition, Forms of Mother Clay, was first curated for the Crafts Museum in Delhi. It pioneered some of the best curatorial practices. Another precious exhibition, Unknown India, on tribal ritual art, curated with art historian Dr Stella Kramrisch for the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1968, took the art world by storm. He also contributed to the richness of the Festival of India exhibitions in UK, USA and Japan, challenging rigid binaries by drawing attention to powerful artistic imaginations at work.

Several interesting stories unravelled at Haku Shah’s remembrance meet at NGMA. His son Parthiv’s story of a Vaghri woman hawker who would visit their home in Paldi, Ahmedabad with a basket full of clay toys day after day, encouraged by his father to create new art forms. Some of her work are part of the permanent exhibits at the Philadelphia Museum. Professor Parul Dave’s story of Saroja, the impoverished wife of a locked out textile mill worker who was encouraged to make figurative appliqué that was later celebrated worldwide, was an eye-opener. Manu Parekh’s story of Gopal Jogi, an itinerant ballad singer from a drought-hit area in Rajasthan, who was working as a stone breaker at a construction site when Shah spotted him and encouraged him to draw, uncovered his potential as an artist. Shah’s visceral engagement with rural, tribal art for more than half a century and his crusade-like zeal in promoting artisans was remembered with great affection by Rajeev Sethi.

As a teacher, Shah mentored generations of students at the National Institute of Design, taught at the School of Architecture and joined the University of California in the spring of 1991 to teach a studio course in Textiles and Design as a distinguished Regents’ professor. He was a conscientious researcher and authored several books and monographs on folk and tribal art, deconstructing the semiotics of rites and rituals embedded in nature and earth with eminent scholars like Eberhard Fischer, Stella Kramrisch, Joan Erikson and Charles and Ray Eames. His book on Votive Terracottas of Gujarat has acquired a cult status. Jyotindra Jain, who partnered with him to research on Temple Tents for the Mother Goddesses in Gujarat, a 225-page monograph with 460 plates, spoke about their shared passion for research that would often keep them awake till 2 at night as they roamed the streets of the old city of Ahmedabad to study the nocturnal rituals of Matani Pachedi artisans.

One of Shah’s most seminal contributions was establishing an ethnographic Tribal Museum at the Gujarat Vidyapith and a crafts village in Udaipur. His own body of work resonates at many levels, from the tender, visual rendering of nirguna poetry and imagery derived from folklore to potent expressions of Gandhi’s satyagraha in a 2015 exhibition evocatively titled Nitya Gandhi. Glimpses of his work on the beautiful memory wall created by the NGMA team, Vidya Shah’s exquisite rendering of Kabir’s songs, Jhini Chadariya and Naiharwa Humka Na Bhave, Antara’s luminous weavers’ song taught by her grandfather and Anant’s poignant tribute to his dada who would not have liked all this fuss was what made the evening at NGMA so special.

(The author is a former civil servant and currently the adviser to the Crafts Museum).