Before his final disillusionment with Gandhi and Congress, he was truly neutral about various communities. Poet Sarojini Naidu had described him as a true ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity

It was well-known that in 1947, Pakistan was a geo-political idiosyncrasy in several ways. First, its architect, engineer and founder, Quaid-e-Azam MA Jinnah, was not a purist Muslim, who led the creation of a ‘New Medina’. The Caliph at Istanbul was exiled and the institution of the Caliphate, established in 661 AD, was abolished by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the moderniser of Turkey. But how was Jinnah not a dyed-in-the-wool Muslim? His grandfather, Jeenabhai, was converted from being a Hindu Lohana to an Ismaili Khoja. The family belonged to Dhoraji, not far from Rajkot. The area, and in fact, the entire peninsula of Saurashtra, then called Kathiawar, had hardly an Islamic atmosphere. Junagadh, in the south-west of the peninsula, was the largest of the area’s princely state headed by a nawab, with a Muslim population of some 12 per cent.

Jinnah’s family shifted to Karachi to do bigger business but grandson, Mohammed Ali, long before at the age of 16, moved to London to become a Barrister-at-law. There he took to the English way of life and soon became a brown Englishman, which during the high noon of the British Empire, was not uncommon. He took four years to return to Bombay (now Mumbai). His three older sisters were married and moved with their in-laws. The youngest sibling, Fatima, Jinnah took under his wings and began educating her at Bandra (a suburb of Bombay) in a Christian missionary school. He was not very close to his younger brother, Ahmed Ali, yet gave him a regular allowance, sufficient for him to marry a Swiss lady, who bore him a lovely daughter before departing for good for her European home.

Professionally, life was somewhat difficult; briefs were difficult to come by for a new Barrister. The acting Advocate-General of Bombay, John Molesworth Macpherson, however, took to Jinnah and got him an appointment as Bombay Presidency magistrate at a handsome salary of Rs 1,500 a month. As a Barrister, Jinnah came in contact with Westernised Parsis, upper-class Gujarati businessmen, solicitors and only a few rich Muslim clients, mainly Khojas, some Memons and Bohras, all converts from Hindus. The first named were like Jinnah himself, the second also recently converted from Kutchi Lohanas and the last were Brahmins before becoming Shia Muslims a few centuries earlier. All the three spoke Gujarati as their mother-tongue like Jinnah, except that the Memons were also at home in Kutchi dialect.

Otherwise, the Qaid-to-be was at home in English, written and spoken. Urdu remained far for him until he began to address mass meetings, especially while campaigning for the crucial 1945-46 general elections. It was too late and the Qaid addressed his mass audiences in English, which most did not follow. In those days, there was no system of simultaneous translation as in the days of Indira Gandhi.

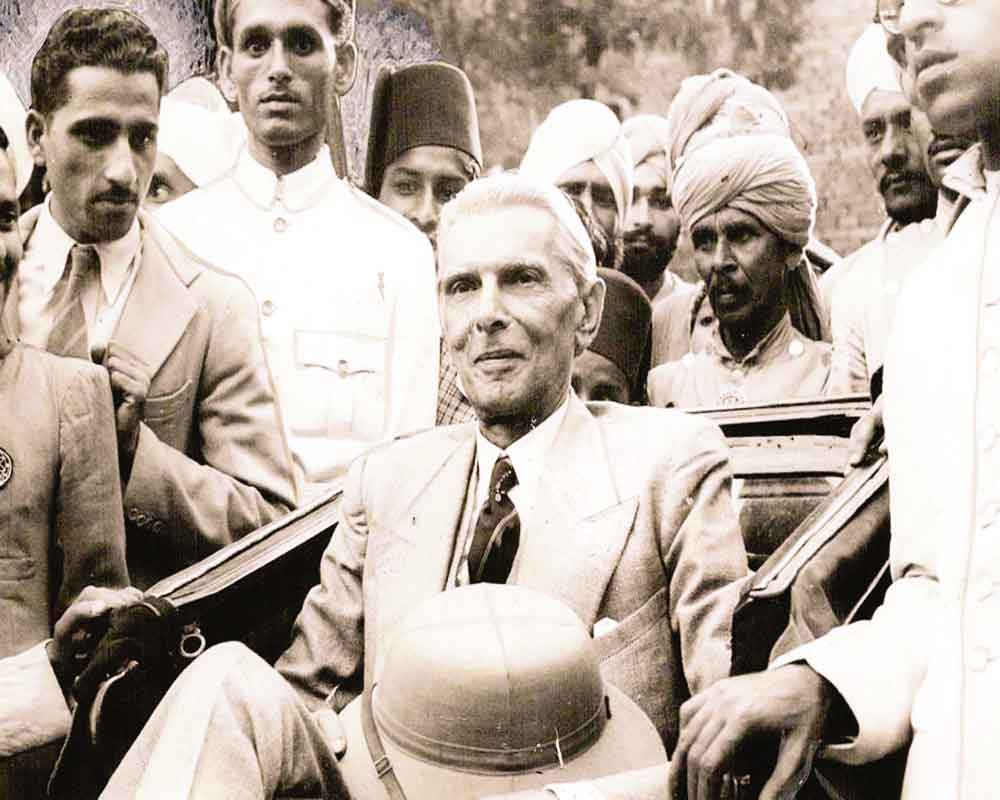

Pran Chopra once reported on a 1945-46 meeting he was covering at Jalandhar. It was evening and the crowd comprised a mass of thousands. In the middle of it, the muezzin called for namaz. Willy-nilly, the crowd dispersed in order to pray. Meanwhile, Jinnah sat down on a chair on the platform, brought out a cigar, lit it and had several puffs before the crowd returned. He resumed speaking quite nonchalantly and the audience shrieked and shouted whenever there was a reference to “Islam is in danger.” He had become a foreigner in many of his ways and habits, and his followers of the mid and late 1940s did not mind one bit so long as he would get them Pakistan. They rightly believed that he was the only leader, who could get them their Pakistan, the land of the pure. Those who lived in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar or Bombay had nothing obvious to get from Partition.

Hijrat or migration, like Prophet Muhammad’s flight from Mecca to Medina in 622 AD, sounded religio-romantic. Nevertheless, it was generally a tough call to be a muhajir in Pakistan as it turned out certainly. Yet, students from the Aligarh University also went to Punjab to campaign in 1945 for Partition. Such was the virus of hysteria that swept through what is India post-Partition, but not half as much in provinces that were likely to go to Pakistan.

The people of say, West Punjab, Sind, NWFP and East Bengal, did not feel half as excited; although certainly they were not unhappy. It is doubtful if Jinnah had before the election campaign, been to most areas outside the provincial capitals. This was one of the reasons for his lack of a correct assessment of his newly-won country. We must also remember that before his final disillusionment with Gandhi and Congress at the Calcutta (now Kolkata) session of the party, he was truly neutral about various communities. Poet Sarojini Naidu, popularly called the nightingale, had described Jinnah as a true ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. After his leaving Karachi at the age of 16, he had, until his parting of ways in Calcutta, never weighed people in terms of Hindu and Muslim.

When the Gandhi finally returned in 1915 from South Africa, his first public reception was held at Gokuldas Tejpal Hall. Jinnah presided over the meeting; when Gandhi had to stand up to reply, he started by saying how happy he was that a Mohamedan leader of eminence should welcome him and say such nice things. Jinnah for his part was mightily annoyed that Gandhi should talk about a leader by his referring to his religion. What had that to do with the function or its programme? His brother Ahmed, a friend of this writer’s grandfather, Dharamdas Vora of 401 Girgaum Road, Bombay-2 (of 1946), had said, “We are not authentic Muslims; we are culturally Parsi. We do not know how to pray by doing namaaz. My brother did not have appropriate garments for prayers until he returned to India in 1935 as life president of the Muslim League. We normally wear lounge suits, my brother prefers those tailored in Savile Row, London. We eat and drink what we like.”

Indeed, Jinnah’s love for the English way of life can be gauged by the fact that he owned some 200 Savile Row formal suits and was always impeccably dressed in public. His shift to the pyjama-achkan attire in his later avatar as the Muslim League president and Prophet of Pakistan notwithstanding, Jinnah insisted on reverting to his Savile Row self when he was sick and dying. “I will not travel in my pyjamas,” he reportedly asserted, insisting that he buried in them. The late Justice MC Chagla, in his autobiography Roses in December, made a reference to Mohammad Ali eating sandwiches lovingly made and brought by his wife Ruttee for her husband. Incidentally, she was not a Muslim but a Parsi. His only child was Dina, who married Sir Neville Wadia, a distinguished Parsi industrialist.

Thus, Quaid-e-Azam Jinnah did not qualify to be, by any means, an ideal Muslim. When he felt jilted by the Congress in Calcutta, he left the metropolis with tears in his eyes as he bid goodbye to his friend Dewan Chand at Howrah station. Before long, he went away to London to set up his practice there. He bought himself a commodious bungalow with a spacious garden. Daughter Dina joined him to go to an upper-class school. Soon, he became the highest paid barrister in the British Empire. He had no plans to return to Bombay until Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, on behalf of the Muslim League, was able to persuade him to return as life president of the party.

(This is the first in a two-part series on MA Jinnah by this columnist. The second will appear here this week. )