The time has come to reflect on the current process under the UNFCCC. Rather than coming up with sterile drafting of weak resolutions for COP 26, we should adopt a different approach

The year 2019 has seen the spread of massive protests in several parts of the world — extending from Argentina and Chile to Lebanon and Iraq. The mobs indulging in these protests have, in several cases, not relented at all, leading to violence that has led to several deaths as in the case of Iraq. There is clearly a common thread of anger demonstrated by the people of some of these countries, which is taking on the form of collective protests and large-scale demonstrations. The protests taking place in India over the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) may very well appear as an extension of this trend that people have witnessed in other parts of the world against Government policies and actions.

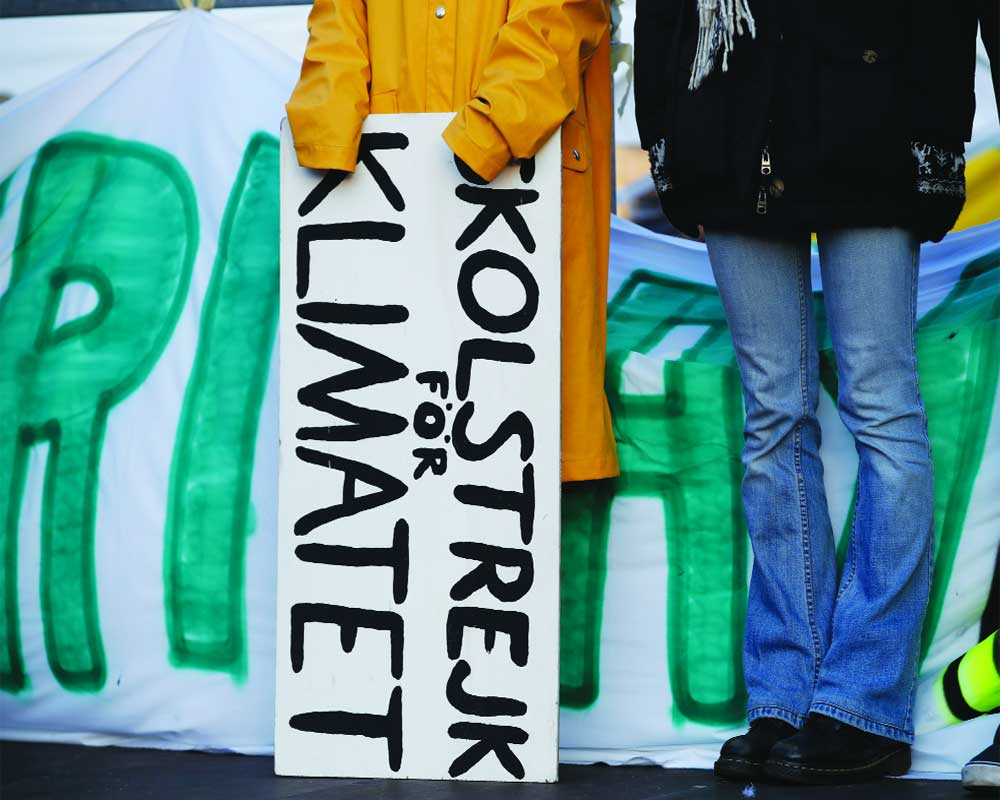

However, it is a rare precedent to have worldwide protests related to global issues where the United Nations (UN) may be involved. No doubt, the UN’s actions have often angered countries, who feel they have been short-changed or discriminated against by any specific decision. But rarely have we seen protests all across the world on global issues that are guided and pursued by some branch of the UN. Hence, what we see today is, perhaps, an expression of universal distress and disgust. It is significant that a young 16-year-old girl from Sweden, Greta Thunberg, is demonstrating against global inaction on climate change. Yet, despite the major protest rallies that have taken place worldwide every Friday over the past few months, we find inertia and inaction at the global level. The 25th Conference of the Parties under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) proved not only to be a frustrating exercise in all respects but sadly, a total disaster in what is required on the basis of the science of climate change.

The Paris Agreement of 2015 has clearly laid down the limit of warming by the end of this century not to exceed 1.5oC. With business as usual and on current trends, the world is likely to reach anywhere between 3oC to 4oC in 2100 unless we wake up and take urgent and effective action. It was in the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) produced in 2007 that a clear case was made scientifically to show that even with a 2oC increase by 2100, the concentration of Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) associated with such an increase would require peaking of emissions no later than 2020.

Yet, despite the UNFCCC having come into existence over a quarter century ago, emissions of GHGs have been going up consistently over this period and particularly over the last two years. The requirement of moving away from fossil fuels to low carbon sources of energy has largely been ignored by countries and vested interests, which want to continue with easy profits in the short-term, despite the increasing risks that the current generation of youth and those yet to come would face.

The IPCC had brought out clearly as far back as in 2011 the stark finding that there would be an increase in frequency and intensity of extreme events as the temperature increases on account of human-induced climate change. There is now growing evidence apparent to everyone that heat waves, extreme precipitation events and sea level rise-related extreme events are on the increase in frequency and intensity. The result is death resulting from extreme temperatures, large-scale flooding in several parts of the world, raging forest fires in California and Australia and even in the Siberian region. There is growing intensity of hurricanes and cyclones, which have caused devastation as in the case of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.

It is becoming increasingly clear now that the process currently being followed under the UNFCCC is not working. It is to be questioned whether after 25 years of this framework convention, we have achieved anything to be satisfied about, when we have crossed 400 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide with no sign of emissions going down as a result of actions under the UNFCCC. Science clearly tells us that emissions of carbon dioxide must reach zero levels by 2050 if not earlier. A sharp and immediate reduction in emissions to achieve this goal might just give us a margin of safety against the growing risks from the impacts of climate change. The COPs, which are held annually under the UNFCCC, see increasing numbers of people descending on the locations where these two-week long wasteful meetings take place, adding to the carbon footprint of the world. But nothing is achieved as a result.

COP 25, which was expected to yield several positive results, suffered from the obdurate stance of countries like the US, Saudi Arabia, Brazil and others, who did not even allow wording to express the need for growing ambition of all the countries of the world, which could have guided collective action in the next COP to be held in Glasgow.

The time has probably come to seriously reflect on the current process under the UNFCCC and rather than coming up with sterile drafting of weak resolutions at the end of COP 26, we should, perhaps, come up with a total different approach. There is a need to urgently address what several have termed as the “climate crisis.” We owe nothing else to our children and grandchildren, who have every reason to hold us responsible for being the most irresponsible generation to have lived on planet earth.

In very specific terms, COP25 was a major disappointment because firstly there was no agreement in the creation of a carbon market. In the ultimate analysis, if low carbon technologies have to be developed, this would happen rapidly if there was a price on carbon providing an incentive for alternative means of energy supply.

The other major disappointment was, of course, a clear statement on the level of ambition, which would guide submissions by national Governments when they meet again at COP26, pledging a new set of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). It is crucially important that collectively nations commit themselves to an increased reduction of GHG emissions when this subject comes up for review during COP 26. Finally, developed countries need to put their money where their mouth is. There has to be a substantial increase in funding of climate change-related projects in the developing world and any such increase has to go beyond current levels of development assistance, which in any case are totally inadequate. Can the developed world find this level of ambition to save the world from unacceptable risks in the future?

(The writer is former chairman, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2002-15)