History neglected archaeology, focusing on kings and politics, relegating artifacts to museums, writes Raju Mansukhani

History, especially political and military history, owes archaeology a huge apology. For far too long, historical narratives have centered around kings and courts, politics, diplomatic battles, and military might, while archaeological excavations, findings, and artifacts are conveniently confined to museums, archaeological sites, and scholarly journals.

When the story of Buddhist collections at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai, was detailed in The Lost Stupa of Kahu-jo-daro, subtitled An Attempt at Reconstruction and The Buddha Within: Images of Devotion and Piety, in 2022-23, there was redemption of sorts. Suddenly, archaeologists, surveyors, and museologists were heroes occupying center stage. Nameless and often not recogniSed for their pioneering efforts, these magnificent men and women are now giving archaeology a rousing start, most appropriately when our nation commemorates its 75th year of Independence and Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav.

“At CSMVS, Mumbai, we go back a long way in time with our Buddhist collections: To 1906 precisely when the first Buddhist object was gifted to the museum. It was a plaster bust of the Gandharan Buddha, created by John Lockwood Kipling just a few years after a committee had been formed to determine the feasibility of having a public museum in Bombay,” wrote Dr Himanshu Prabha Ray in The Buddha Within.

John Kipling, an art teacher and curator, deserves special mention not only because he traveled, sketched, and documented the north-western parts of the Indian subcontinent, but also because he was the father of the more famous Rudyard. Rudyard Kipling did his illustrious father proud as he immortalised the British Raj through novels, short stories, poems, and, of course, his news coverage for The Pioneer from 1883-89, which was published from Allahabad.

These stories within stories are fascinating when we learn that John Kipling spent years at the Lahore Museum as a curator, besides heading the Mayo School of Industrial Art where students learned to make plaster casts, adding to the collections of new and existing museums. In Lahore, there was a surfeit of artifacts from Gandhara (present-day states of Pakistan and Afghanistan), and the Gandharan Buddha bust showed Graeco-Roman influences, which endeared John Kipling, explained Dr. Ray.

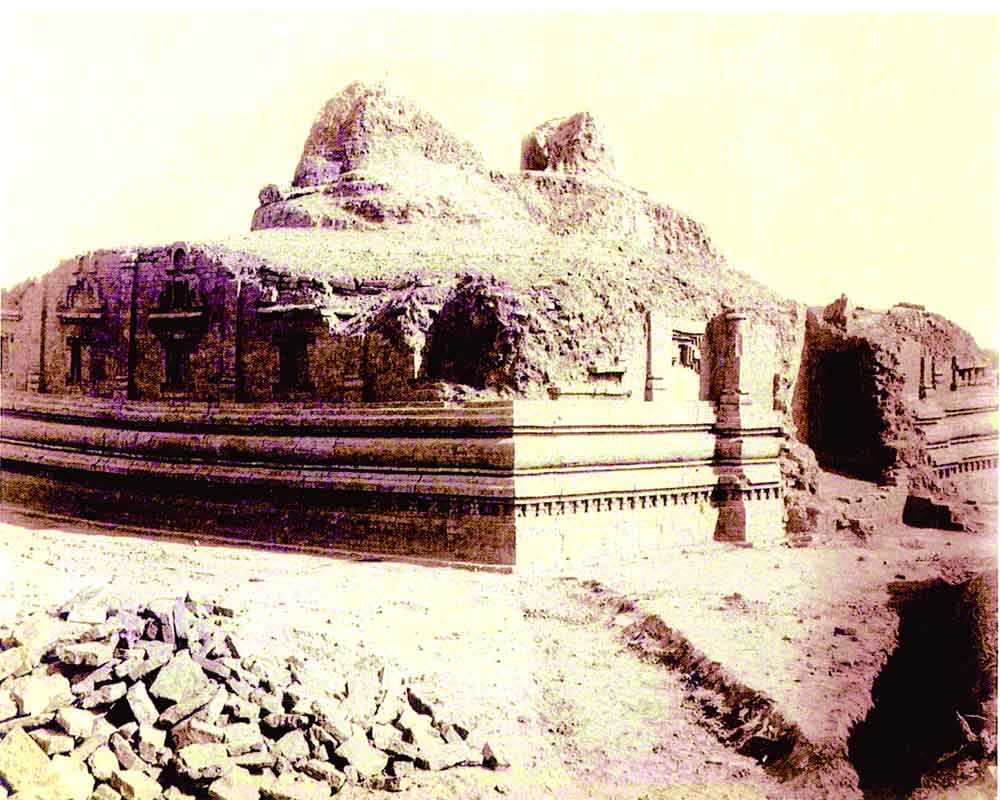

ASI expertise: From 1880-90, the Archaeological Survey of India stepped up operations; their archaeologists, surveyors, and draftsmen optimised the opportunity to do exemplary work and make history. They had been trained in surveying, documenting, photographing, cataloging, and exploring the vast countryside. Henry Cousens now played a critical role as he traversed across the Western Ghats: rock-cut Buddhist caves in Bhaja, Kondane, Pitalkhora, Karle, Nasik, Junnar, Ajanta, and Ellora caves. Cousens and his team then documented the brick-built stupas in Boria (near Gujarat) and Sopara, north of Mumbai, as well as the Mir Rukan and Kahu-jo-daro stupas in Mirpurkhas in Sindh (now Pakistan).

“It was in Mirpurkhas that Cousens recorded the remains of architecture around the stupa, such as monasteries, small votive stupas, and clay tablets. The core of these stupas comprised sun-dried bricks while the exterior casting was of decorated burn bricks (terracotta),” wrote Dr Ray.

History lovers and those drawn towards Buddhism for its spiritual moorings often wonder what was contained in the stupas, given the innumerable structures spread across the length and breadth of our subcontinent. In the case of Kahu-jo-daro, it was revealed that ‘a stone relic casket was found inside the stupa. The casket contained a small crystal bottle covered with white sand and several precious offerings - coral and crystal beads, seed pearls, four gold beads, one small gold-wire ring, ten copper coins, some small lumps of charcoal, a few grains of unidentified materials, and some other odd beads. Inside the bottle was a small, silver cylindrical case containing an object the size of a pinhead, wrapped in a gold leaf.

The excavations at Mirpurkhas were considered of great significance as this was the third stupa in the-then Bombay Presidency to yield relics after the stupas at Sopara, excavated by BhagwanlalIndraji in 1882, and Junagarh in 1889.

When Henry Cousens began the site excavations in 1909-10, he was superintending archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India; and more importantly he was a committee of the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay. He decided to place the finds in the Prince of Wales Museum, including relic caskets found in the stupa. In the 1960s, the relics were transferred to Sarnath and enshrined in the newly-built Mulagandhakuti temple at the site. Once again, a memorable story within the story of archaeology that’s worth recounting.

Largest collection: It was in 1919 the terracotta images and bricks excavated from the Buddhist stupa at Mirpurkhas were formally handed over to the-then Prince of Wales Museum (now CSMVS) by Cousens. Through the 20th century, legions of venerable historians-art historians and curators like Dr Moti Chandra, Dr Kalpana Desai, Dr Devangana Desai, and Dr Pratapaditya Pal contributed their collective knowledge, published works and monographs highlighting significance of the Buddhist stupa at Mirpurkhas. They were instrumental in giving modern research on Mirpurkhasits new direction, highlighting riverine cultures, urban centres, trading towns, besides significance of religious places where people prayed, contributed their earnings, keeping places of worship alive through centuries.

For Dr Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director general of CSVMS who helmed the research on Kahu-jo-daro from 2008, it was indeed an uphill task for the project commenced without the benefit of either inscriptions or literary evidence.

"Kahu-jo-daro was remote, and beyond our reach and my material resources were only those in the CSMVS collection," he said, adding that CSMVS has the largest and most comprehensive collection of 297 archaeological finds, dating to the 5th and 6th centuries CE, from Mirpurkhas. A large part of the stupa mound was destroyed since the bricks were required for laying railway lines in the area.

Henry Cousens had noted that despite railway workers digging up the bricks, a significant portion of the stupa remained at the north end of the site. As in the case of Mohenjodaro, the largest of the Harappan metropolises in Sindh, it was railway workers-contractors who provided the ASI with its first leads that the bricks were part of vast ancient sites. Railway teams had no idea of how old the bricks were or their significance. It is amazing that these bricks, of uniform size and shape, had survived for centuries and were now becoming a part of modern transportation systems. Besides papers and notes, Cousens’ book, ‘The Antiquities of Sind with Historical Outline,’ is regarded as a seminal work and provided a credible platform upon which the CSMVS built its research.

Made of sun-dried bricks, the Mirpurkhas stupa has yielded 11 Buddha relief panels, although Boddhisattva icons are rare. In addition, hundreds of unbaked clay tablets with the “ye dharma” verse under the image of a Buddha or a stupa have been found, dating back to the 7th and 8th centuries CE. Thus, by the time of the Mirpurkhas stupa, Buddha’s biography and narrative depictions of stories from his life had been superseded by single-seated images of the Master place in the niches of the stupa. The stupa now enshrined the words of the ‘Enlightened One’ – “ye dhamma hetupadhava” - on clay tablets, Prof Prabha Ray explained.

Buddhism in Sindh: Owing to scarcity of archaeological and literary material it is difficult to know when and how Buddhism found its footing in Sindh region. In the north-west, it was the Gandhara region where Buddhism took a deep root, thanks to efforts of Mauryan Emperor Asoka.

Explained Dr Sabyasachi Mukherjee in ‘The Lost Stupa’, "the great river Sindhu, which is the Sanskrit name of river Indus, passed through the valley from the north to the south and acted as an important trade, religious and cultural connection for the Indus Valley, Punjab and the Gandhara region." This riverine connection, water-highways of the ancient world, had a continuing and deep impact on Sindh’s social, cultural, and economic history, providing crossroads and bridges for people of the region. Buddhism, as a religion and way of life, found adherents in Sindh.

"It is very important for global citizens, especially the young, to understand that the Indian sub-continent was always part of the globalised world," said Dr Sabyasachi, referring to the present era of globalisation which most netizens feel is a historic unique one. Kahu-jo-daro in Mirpurkhas, he emphasised, is not an isolated instance of artistic activity in the area. He drew links between this site of the ruined Buddhist stupa with Takshashila, the chief city in eastern region of Gandhara.

It was time now for the CSMVS team to take up the digital challenge: the team decided on digital reconstruction of Kahu-jo-daro stupa. “We knew it was one of the few examples of decorative terracotta stupa architecture in the Indus Valley, and that is when we began utilising the collection at CSMVS, and some surviving architectural fragments, to begin imagining reconstructing the original shape of the stupa, built probably in 500 CE, even though Sir Cousens assigned the stupa to c 400 CE, a century earlier,” said Dr Mukherjee.

“One can easily imagine the magnificent scene around the stupa in the valley of Kahu-jo-daro,” he said, adding, “the main stupa with its majestic harmika stood nearly 20 metres tall, its towering presence inspiring devotees and pilgrims approaching from over a long distance. Thousands of local devotees, and those from all over India, perhaps even other countries, must have throned here to pay their respects to the great soul whose corporeal remains were enshrined in the stupa.”

The main entrance was embellished with decorative bricks and a torana or gate, as seen in Sanchi too. For pilgrims the circumambulation or going round the stupa is a sacred ritual, followed in Hinduism and Jainism too. At Kahu-jo-daro the visual gallery of seated Buddhas, in niches of the platform walls before entering the stupa, was the source of piety, inspiration and austerity. Shrines inside the stupa would have contained images of the Buddha; it would seem these images were moved to another site, probably to ensure their safety from invasions before the entire stupa itself was covered in sand and left buried, forgotten for centuries.

Kahu-jo-daro, as ‘The Lost Stupa’ details, belonged to a much earlier era, it could have been a reconstruction of a ruined stupa erected under Emperor Asoka’s orders in the 3rd century BCE. Fascinating stories of ‘when’ and ‘where’ of the Kahu-jo-daro continue to grip our attention, inspiring us with the depth of archaeology in our land, thousands of years ago.

Unfortunately, Dr Mukherjee said, recent images of the site indicate the complete destruction of the main stupa, including its plinth as well as surroundings which had remained intact even decades after the excavations undertaken by Henry Cousens. Like the Bamiyan Buddhas, the Kahu-jo-daro stupa is now visited on pages of books, photographs, and its digital reconstruction.

For Dr Sabyasachi Mukherjee, leading CSMVS Museum for almost two decades, there is no underplaying the power of culture to transform our world. “I strongly believe that the power of culture can change the world as it unites people, countries, religions, and customs. It works as a healing tool in our broken societies.” As clouds of war hover over continents, reducing ancient lands and cities to rubble and killing thousands, it is time to pay homage to Kahu-jo-daro and the spiritual, religious, and artistic legacies of Buddhism which are built around peace, oneness, and brotherhood.

(Raju Mansukhani, a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangharalaya, is writer-researcher on history and heritage issues.)