Any so-called economic development at the cost of forests is going to invariably hit vulnerable groups who depend on them

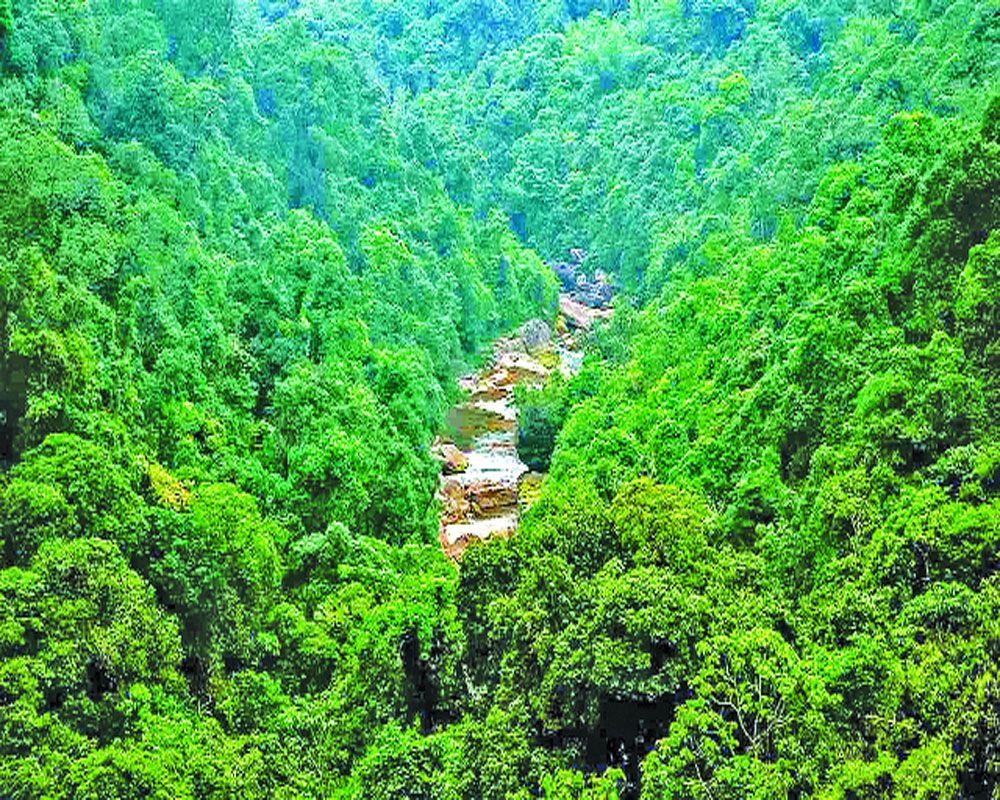

The vast expanses of forests, covering India's diverse terrains, are not just mere geographical entities. They are the unsung guardians of our planet, playing a monumental role in mitigating attrition of ecological services and climate change threats.

Forests are better known as buffers against extreme weather patterns, ensuring consistent water supply, curbing soil erosion, and aiding in sustainable agricultural practices. Besides these, they stand as vital habitats for the majestic wildlife of India, from awe-inspiring tigers to vivid avian species, amphibians, and the insect world. Their loss could mean a stark decline in biodiversity, damaging the intricate ecological systems, and endangering countless life forms including humans.

Less discussed, however, is the fact that humanity has relied on forests, as a primary source of sustenance with a plethora of foods derived through various inventive methods. In modern times, our diet largely revolves around just thirty domesticated species: with rice, wheat, and maize alone making up over half of global calorie consumption. Every domesticated species has its ‘mother plant’ in the forest, the gene pool in its purest form. The decline in wild food resources due to anthropogenic forces and the fading knowledge of their harvesting and processing have led to the shrinking of the variety that populates the human food system. Any crisis because of harm to the cultivated crops on account of development of immunity of pests to pesticides, or due to climate change will simply be catastrophic. Integrating wild edible plants into mainstream diets needs to be explored as it will have the potential of significant implications for environmental sustainability, especially in a world grappling with food scarcity challenges. Given this, the need to conserve forests at any cost can hardly be overstated.

While many underprivileged households often depend on monotonous staple diets provided by governmental initiatives, the tradition and reliance on wild foods and indigenous medicinal systems remain strong, particularly in remote, and economically challenged areas. Any so-called economic development at the cost of forests is going to invariably hit these vulnerable groups, and converting forests indiscriminately into basically low-productivity agricultural lands through encroachments and regularization thereof by Governments for short-term gains needs to be stopped forthwith. For most laymen, forests are primarily vast tracts populated by trees and wildlife. The Forest Survey of India (FSI) paints a more intricate picture while it indicates and includes in the forest cover any territory spanning over a hectare, with a canopy coverage exceeding 10%. According to their latest biennial report, India's forest cover encompasses about 22% of its terrain. This definition and its true contribution to the ecological security of India, though, do raise eyebrows.

The importance of large, continuous forests cannot be matched by the simple summation of smaller, fragmented forest covers, even if they hold equivalent area metrics in the name of compensatory plantations done instead of natural forests diverted for non-forestry purposes under the provisions of the Forest Conservation Act 1980 of India. Ignoring this crucial aspect also contributes to the undervaluation of natural forests and could prompt a decreased emphasis so far as the protection and conservation of natural forests are concerned. One can notice a predominant trend of weakening of the forestry sector. The Global Forest Watch showcases a concerning trend: between 2002 to 2020, India lost around 3,490 sq. km of natural forests.

The Forest Conservation Bill 2023 has recently relaxed conditions required for the diversion of forests for non-forestry purposes in many areas of the country. The penal provisions of the Indian Forest Act 1927 have been amended by legislating a separate Act in the name of The Jan Vishwas (amendment of provisions) Act 2023 lowering the punishments for the offences related to setting fire to cattle trespass and grazing in forest areas. The Biological Diversity (Amendment) Act 2023 has ‘decriminalized’ the offences whereby the offenders can get away by simply paying a penalty amount.

While aiming to meet the objective of promoting bamboo plantations in private areas, the Indian Forest Act 1927 was amended in 2018 which deleted bamboo from the definition of timber making it felling a ‘non-offence’ under this Act in the Reserved Forests. At the heart of the conundrum lies the challenge of appropriately valuing all the goods and ecological services provided by forests and incorporating the same while planning for and assessing economic development. The current economic approaches fail to recognize the contributions of forests which aren't translatable into strict market terms. Forward and backward economic linkages related to forest produce including medicinal plants and also provision of livelihoods to forest dwellers and local communities remain either ignored or unquantified. The critical role in maintaining the water balance in the catchment areas as well as ensuring perennial flow in streams is grossly overlooked. Carbon sequestration and its role in the mitigation of climate change are also not comprehensively accounted for.

As we venture further into the age of sustainability in all spheres; it becomes paramount to re-evaluate, recognize, and incorporate the true worth of our forests in the national economy while ensuring simultaneously that they remain our guarding sentinels for generations to come.

(The writers are Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (UP, Maharashtra); the views are personal)