Since 1949, when Lata Mangeshkar was first noticed for her extraordinary singing talent in the Mahal song ‘Aayega aanewala,’ her magical voice has taken a firm hold of the Indian imagination. For over six decades, as the much loved singer, she has reigned supreme in Indian film music and has been conferred in 2001, the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour, writes Nasreen Munni Kabir in her book Lata Mangeshkar ...in her own voice. An edited excerpt:

Lata Mangeshkar remembers a dream that returned to her every night when she was in her early twenties. Coming home from recording two songs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and two in the evening, she would fall asleep and the dream unfurled: it is early morning and she finds herself all alone at a black-stoned temple by the sea. Unaware of the deity associated with the temple, she makes her way through the sacred space. At the back of the temple, there is a door. She opens it and sees a few steps leading from the door to the dappled water. She sits on the stone steps and the waves gently wash over her feet.

Young Lata thought nothing of the dream but when it reoccurred night after night, and for several months, she decided to share it with her mother, Shudhhamati Mangeshkar, who listened quietly to her and said: ‘God has blessed you. You will be very famous one day.’

Her mother’s reading of the dream could not have been more prophetic. Today Lata Mangeshkar is loved to the point of worship. People speak of her voice as a divine gift and some even talk of her being an avatar of the Goddess Saraswati. She is acclaimed as one of India’s greatest singers, has won countless awards, including the Dada Saheb Phalke Award (1989) and received extraordinary recognition, including India’s highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, in 2001.

Lata Mangeshkar’s fame in the world of Indian music is unrivalled. Unlike many stars whose celebrity status distances them from ordinary people, admiration for her is highly personalised because she is intimately linked to the emotions of millions of people through her songs. No bond could be stronger.

Since 1949, when she was first noticed for her extraordinary singing talent in the song ‘Aayega aane wala’ from the film Mahal, Lata Mangeshkar’s voice has taken firm hold of the Indian imagination. The haunting and timeless quality of the song itself — brought alive through the tuneful purity of her voice and flawless phrasing — had an instant and profound impact on all who heard it. For countless millions, Lata Mangeshkar continues to embody an emotional experience through her solos and duets with Mohammed Rafi, Kishore Kumar or Mukesh. Her songs transcend all barriers of language, region and religion — and her spirituality is present in equal measure whether she is singing a bhajan or a naat.

For decades, she was the most sought-after singer, and every top actress, from Nargis, Madhubala, Meena Kumari, Nutan to Madhuri Dixit, wanted Lata as their voice. She remains a widely respected figure in the Indian film industry and is affectionately called ‘Didi’ [elder sister] by all. Lata Mangeshkar is the highest-selling Indian artist and has made fortunes for Indian record companies. Her songs have helped spread an appreciation of Hindi film music throughout the world. In India, she has achieved iconic status, and created everlasting music that has become the soundtrack to our lives.

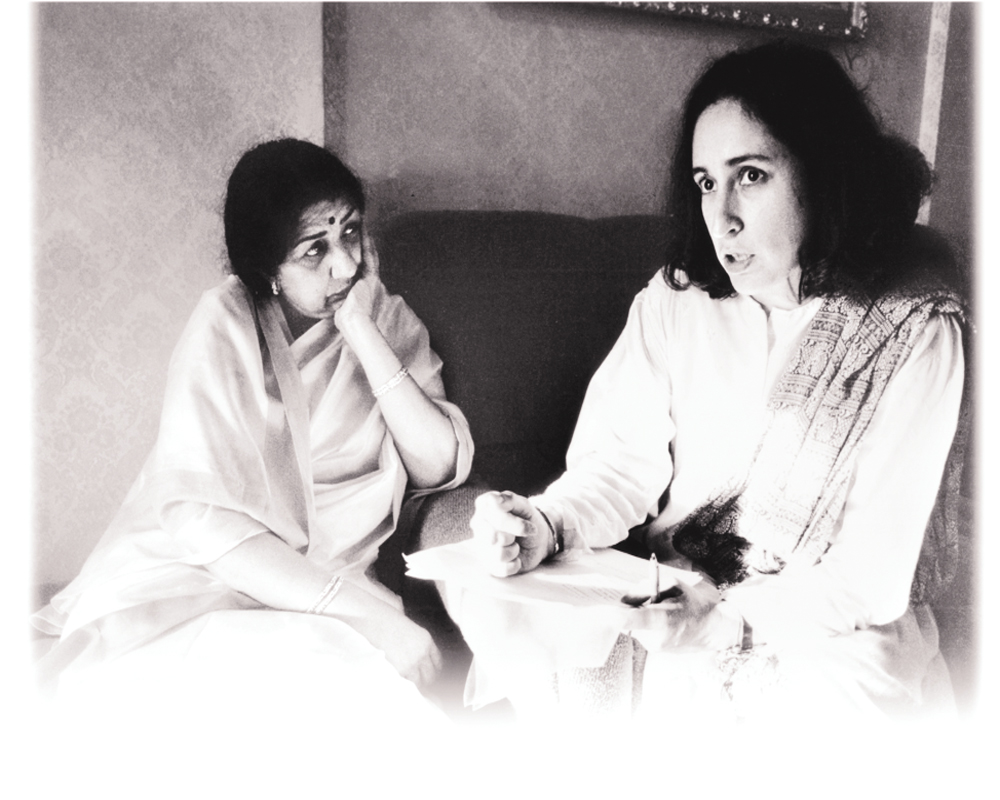

Based on Lata in Her Own Voice, a six-part documentary series that I directed in 1991, [produced by Hyphen Films Ltd for Channel 4 TV in the UK; Commissioning Editor: Farrukh Dhondy], this book was set in motion through an email addressed to Sanjeev Kohli, composer Madan Mohan’s son. Sanjeev Kohli played a crucial role in the making of Lata in Her Own Voice and I sought his advice again to see whether we could preserve in book form the extended interview with Lataji that I had recorded for the film. With characteristic and lightning speed, Sanjeev Kohli emailed back: ‘Didi says go ahead.’ I then asked whether we could update the material, make it longer, more conversational, and fill in any gaps that might be apparent.

Once I had her agreement to the idea of a ‘book of conversations,’ I called her several times a week between May and August 2008. We went over the original interview and covered many new areas of discussion. She sometimes talked in English but most often in Hindi. I immediately typed her answers on my laptop, translating them into English.

Lataji was always open, warm and candid. Her memory for songs and dates was astounding. When asked the name of a song she had sung for Ghulam Haider or Naushad, her recall was instant, despite the fact that she has recorded several thousand songs and was being asked to remember something that had taken place over fifty years ago. And when she could not recall a song or a date, she had no hesitation in saying to me: ‘I don’t remember.’

Sometimes a telephone conversation had a strangely humbling and unnerving effect on me. While discussing ‘Aayega aanewala,’ when I asked if we could include the beautiful opening lines of the song in our book, she said: ‘You need the words? You can write them down.’ She then proceeded to hum, half-sing and recite from memory:

Khaamosh hai zamaana chup chaap hain sitaare

Aaram se hai duniya bekal hai dil ke maare

Aise mein koi aahat is tarah aa rahi hai

Jaise ke chal raha ho mann mein koi hamaare

Ya dil dhadak raha hai is aas ke sahaare

Time stands still. The stars are silent

The world is at rest. Yet my heart is uneasy

Suddenly I hear footsteps approaching

As though someone were walking through my heart

Or is it the sound of my heart quickening with hope?

I was too embarrassed to tell Lataji the kind of effect hearing her half-sing, half-recite the poem had on me. Remember, this was Lata Mangeshkar on the line, not a recording! Sitting in my Maida Vale flat on a sunny London day, I felt a rush of emotion, a sense of being an unworthy eavesdropper who happened to hear a bit of living history.

Lata Mangeshkar’s songs are living history — so strongly tied to all our life stories and articulating our many emotions. Once the lyrics were typed in, our conversation continued and we talked of other things.

This is how the book slowly took shape: we would talk, I would type and during our next call, I would read back the translated conversation to her and she would say: ‘Yes, that’s it. But it was in 1945 not ‘46.’

After a month of phone calls, I wondered why it was so easy to translate Lataji. And then it dawned on me: her voice is so utterly expressive that her tone dictated the most fitting word to use. You knew when ‘resigned’ — as in ‘Lataji said in a resigned tone’ was right — and when ‘meekly’ painted a more accurate picture of how she reacted at a particular moment. Lataji expresses subtle shades of meaning — emotional and psychological — and so for the attentive listener nothing is lost. It is this gift of being expressive that comes through her voice and when she sings ‘Ajeeb dastaan hai ye,’ ‘Chandni raatein pyaar ki baatein,’ ‘Ai dilrubaa nazaaren mila,’ or ‘Lag jaa gale,’ she stirs an emotional response.

From a more technical perspective, it made complete sense to me why so many composers have marvelled at Lataji’s uncanny ability to instantly grasp both the tune and the emotional import of a song. She is a brilliant actress, and though unseen, her voice adds hugely to the scene’s drama and intensity. An actress lives with the character she is playing for many months and so comes to understand how to deliver dialogue and judge the pitch of performance. Lataji is able to grasp in an instant the psychology and emotional map of a character, and like the best male playback singers such as Mohammed Rafi, Kishore Kumar and Mukesh, who have also achieved this, she sings in character. In her voice there is total identification and empathy with the character’s depth of feelings.

There are many examples in which we see how Lataji’s singing enhances the impact of a scene. Think of Nargis miming ‘O mere laal aaja’ in Mother India or Meena Kumari in ‘Chalte chalte’ in Pakeezah, or Nutan in ‘Suno chhoti si gudiya ki lambi kahaani’ in Seema. An interesting question to ask is whether Lataji is singing for the actress or the actress’s performance is determined by Lataji.

Her musical skill is well known and widely appreciated, but her natural acting talent and her mastery of the intricacies of language and poetry is equally remarkable. During our conversations, she repeatedly said that for her, lyrics were the most important aspect of a song. She has always preferred songs that say something about feelings and are not just catchy tunes.

From September 2008 to March 2009, Lataji and I went through the entire manuscript, page by page, word by word, to avoid any errors that might have been caused by phone crackle. As I read the manuscript to her, she listened with complete attention, gently correcting and elaborating.

There is a deluge of misinformation on Lata Mangeshkar and I found dozens of very imaginative tales on the Net, including one that claimed that Lataji, on hearing that Master Vinayak had died, cried the whole night and then thought Lord Dattatraya was standing before her telling her to be brave and to carry on struggling through life. When I asked her if this had really happened, straightaway Lataji said: ‘No, it didn’t.’

Excerpted with permission from Lata Mangeshkar… in her own voice by Nasreen Munni Kabir; published by Niyogi Books