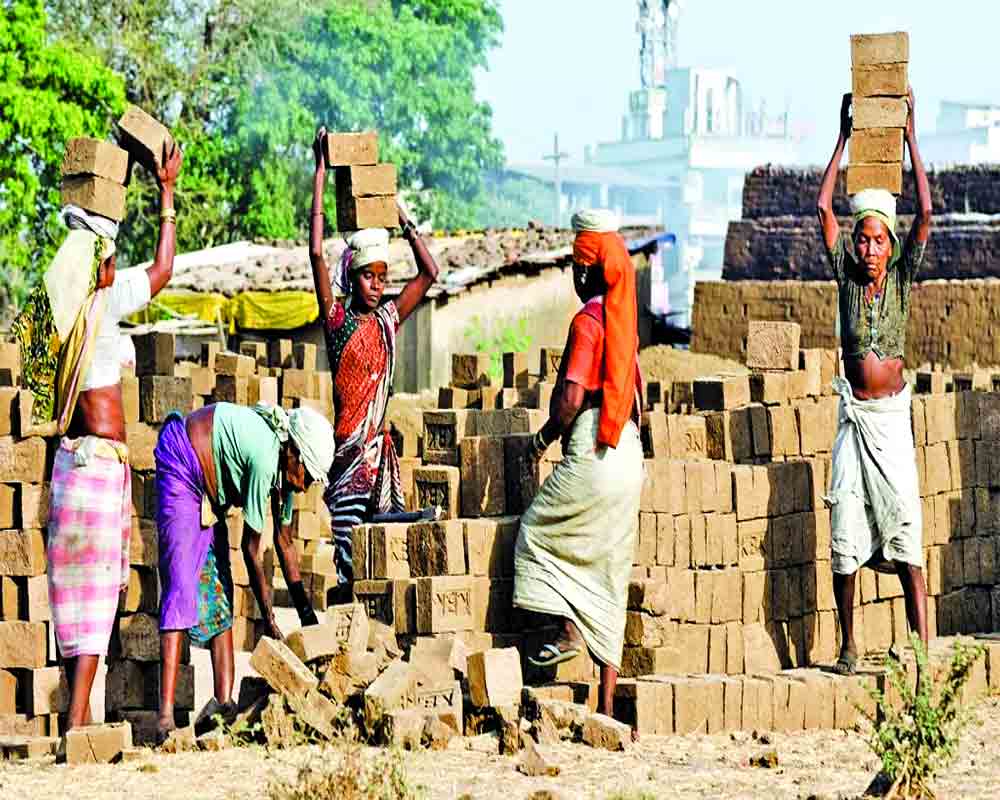

Despite strict laws, men, women and children continue to be exploited in conditions reminiscent of the days of slavery

My father had taken a loan of Rs 7,000 from a bhatta maalik (brick kiln owner) around four decades ago for my grandfather’s treatment. He could not survive but our whole family started working in his brick kilns as bandhua mazdoor (bonded labourers). My father died 15 years ago, but I am yet to repay that loan. I do not know how much loan is left, but the maalik (owner) says I will have to work for a couple of years more,” said Sukhai Ram, Village Masauli, Barabanki, 30 km south-east of Lucknow, the state capital of north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

Slavery is illegal and banned in India. There is a strict law to protect bonded labourers, but millions of men, women and children live and work in slave-like conditions — bonded labour, sex trafficking, child labour, domestic servitude and many other forms.

A global survey report says that 18 million people, which is 1.4 per cent of India’s population, work as slaves in brick kilns, the carpet industry, glassware and bangle industry, besides children who work as domestic help or at roadside eating joints. However, several civil rights activists in India believe this number is just the tip of the iceberg.

The latest figure available from the Human Rights Commission shows over 14 million children living under slavery. “If one does an honest counting, this number would surely jump to twice

that — perhaps closer to 30 million,” said National Convener of People’s Vigilance Committee on Human Rights (PVCHR), Lenin Raghuvanshi. “Men, women and children are forced to work as bonded labourers in brick kilns and the bangle industry,” he added.

Surojeet Chatterjee of ‘Save the Children’ said that the number of working children between the age group of five and 14 years in Uttar Pradesh is 2.1 million. “This is the number which we know of, but the number of children working in rural areas or in those sectors where the reach of civil rights activists is almost negligible must be very high. The law says children should go to school and should get time to play. But this is not happening,” she said.

The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act of 1976 outlaws all debt bondage, including that of children. In addition, under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), rape, extortion, causing grievous hurt, assault, kidnapping, abduction, wrongful confinement, buying or disposing of people as slaves, and unlawful compulsory labour are criminal offences, punishable with up to 10 years imprisonment and fines.

Under the Juvenile Justice Act, 1986, cruelty to juveniles and withholding the earnings of a minor are criminal offences, punishable with up to three years of imprisonment and fines. “The laws are there but these are not implemented,” said convener of the PVCHR Lenin Agnivesh.

Raghuvanshi believes bonded labour is a contemporary form of slavery. “If it is still existing, it is a clear reflection of the failure of the welfare state. The Government, which is supposed to provide them basic necessities, has failed them. As they are poor, they move out to eke out a living in cities and end up as bonded labourers in brick kilns and factories,” he added.

The US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in its report in 2016 had said that India has 12 to 14 million slaves, more than any country in the world. There are 27 million slaves in the world. How does a country like this have 12 to 14 million slaves in 2016.

The majority of these bonded labourers are migrant workers who shift from impoverished regions like Bundelkhand, Bihar and Jharkhand in search of work. In brick kilns, the entire family works as a team. “These migrant workers are allotted a piece of land by the owner where the workers have to dig the earth and then wet it with water to make the mud suitable for the moulding process. Generally, for moulding, the whole family is engaged, including young children,” said Convener, Voice of People, Shruti Nagvanshi.

The labourers are paid Rs 200 for making 1,000 bricks, which are then sold in the market for Rs 7,000. These labourers are recruited by agents, who ask them to take their families along. “It is an attractive prospect where one is allowed to take his family with him. The labourer is promised accommodation and is often paid an advance — which is a veiled term for debt. Once he accepts the advance, he falls into the trap,” she explained.

Studies carried out by different agencies also point to the alleged sexual exploitation of women in brick kilns. Radha (name changed) was lured from her village in Jharkhand on the pretext of a job by another woman and sold as a bonded labourer in a brick kiln at Jaunpur. She told human rights activists that she was raped daily by the brick kiln owner and was beaten up when she protested.

Young children are the worst sufferers though. They do not go to schools and instead help their parents arrange bricks for drying, and collect the broken and improperly moulded bricks. Once they get older, they are drawn into this trade having been trained from a young age.

Kamla, the mother of five, revealed how her two youngest children, Medhu (5) and Rani (3), used to cry for food. With barely Rs 200 she made for making 1,000 bricks, she didn’t have enough to feed her family, and her daughter died of malnutrition before she could turn four.

Workers employed in brick kilns mostly belong to the Schedule Caste (SC), Schedule Tribe (ST) and minorities, which are usually non-literate and non-numerate. They do not easily understand the arithmetic of loan/debt/advance, and documentary evidence remains with the creditor and its contents are never made known to them.

Shamshad Khan, secretary of Centre for Rural Education and Development Action (CREDA), which works in the carpet belt of Bhadohi in Uttar Pradesh, said that child labour might not be visible on the surface, but clandestinely it is still happening.

“Migrant workers from Bihar and Jharkhand are forced to live in closed sheds operated by carpet manufacturers. They come with their families and are not allowed to mingle with others,” Khan revealed.

But in the bangle industry, slavery has been given a legalised shape. “A person is allowed to give a final shape to glass bangles at his home and is paid Rs 6 for 350 bangles. The entire family works for 12-14 hours a day to prepare 30 such lots. So, after a day’s hard work, the person gets only Rs 180. He employs his children in this trade so that he can earn more. Gradually, the child who should go to school is sucked into this bangle-making business,” said Dilip Sevarthi, National Convener, Campaign for Women and Child Rights.

He said bonded labour is the worst form of human rights violation and a contemporary form of slavery. It is a violation of the Right to life, Right to Equality and Right to Individual Dignity.

(The author is a senior journalist)