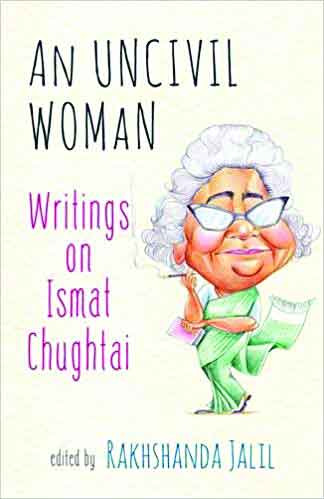

An Uncivil Woman

Author : Rakhshanda Jalil

Publisher : OUP India, Rs 550

This book offers critical insights into the works of Ismat Chughtai and discusses the position of the controversial author vis-a-vis the Progressive Writers’ Association, writes KALYANEE RAJAN

Ismat Chughtai (1911-1991) was a fearless and trailblazing stalwart of Urdu fiction, unequivocally one of the four pillars of modern Urdu short story, the others being Manto, Krishan Chander and Rajinder Singh Bedi. She was a little above eighty at the time of her death, having led a largely uninhibited life, could be safely termed a rebel since her birth, made unconventional choices whether in terms of life or career and made it her explicit agenda to expose the hypocrisies peppering the lives of the contemporary middle class Indian society, Muslim households in particular because she lived in one and saw the chinks ever so closely from that vantage point.

Rakhshanda Jalil’s An Uncivil Woman: Writings on Ismat Chughtai is a valuable addition to the corpus of critical and wholesome appraisals of Chughtai’s life and times, her works and their tremendous impact on posterity. Noted Chughtai critic Tahira Naqvi’s blurb is worth quoting: “Ismat Chughtai, (is) the Grand Doyenne of Urdu fiction, the woman who married a film director, who wrote screenplays and made films, who cooked up a storm for friends and family with the same gusto as she wrote bold, uninhibited and memorable fiction…” Jalil acknowledges the apt title of the instant volume being used from an earlier essay of Geeta Patel titled “Ismat Chughtai: An Uncivil Woman” published in the Annual of Urdu Studies, Chicago-Wisconsin Volume 16, 2001. Apart from a brief and general introduction to Chughtai by Jalil, the volume comprises of fourteen selections wherein four essays are written in English, eight translated pieces are from Urdu to English and two interviews with Chughtai have been reproduced.

In the introduction, Jalil lays bare the extent of Chughtai’s “formidable” oeuvre: Five collections of short stories, seven novels, three novellas, several sketches, plays, reportage and radio plays, stories-dialogues-scenarios for the many films produced by her husband Shahid Latif and others. It must be noted that in her lifetime, Ismat gave several fearless interviews, wrote several pieces of non-fiction, faced obscenity charges alongside fellow writer Saadat Hasan Manto, and in the face of all odds, remained an intensely socially-engaged, politically aware writer throughout who ostensibly seemed to be writing about women but in fact delved with clinical precision into women and their engagement with everything else around them in several reciprocal ways. Jalil underlines the fact that Chughtai’s rather tempestuous and explosive persona overshadowed her literary merit to a remarkable extent. Anyone familiar with the scope of her entire literary oeuvre will note with dismay how Chughtai’s entire career continues to be identified with the frivolous controversy surrounding “Lihaaf”, the obscenity charges and the court proceedings thereafter: The wide anthologisation of only “Lihaaf” and its veritable canonisation by inclusion in university syllabi being a strong example.

The four English critical essays are by Geeta Patel, Tahira Naqvi, Fatima Rizvi and Syeda S Hameed. “Disorderly Discernments” by Geeta Patel, also the longest piece in this volume, runs into a whopping fifty pages where she ostensibly seeks to unpack the several vital layers in Chughtai’s lesser known short story Ek Shohar Ki Khatir and theorises on various vertices of Chughtai’s critical engagements including gender, genre, ideology, Zenana fiction and biofiction, excavating Chughtai’s following of mentor and precursor Rashid Jahan, most significantly “unpacking the (convoluted ideological) apparatus” that has gone into Chughtai’s construction of the story.

The next essay by Tahira Naqvi discusses another crucial aspect of critical analysis as one approaches Chughtai’s works — that of translation. In an essay titled “Looking for Chughtai: Journeys in Reading and Translation”, Naqvi reminds us that Chughtai was an ‘unselfconscious’ feminist, who nevertheless took an “audacious and strident approach to life and to writing”. Naqvi has translated most of Chughtai’s works into English and therefore shares crucial insights into the hallmarks of Chughtai’s writing which at the same time proved immensely difficult to translate, the unique ‘begumatizaban’ for instance, used by middle class women and begums of the Urdu-speaking households. In ten crisp pages of her fascinating essay Naqvi brings alive the enormous difficulties she faced while conveying Ismat in intent and form from Urdu to English.

Fatima Rizvi’s incisive essay titled “Gender, Modernity, and Nationalist Sensibility in Tedhi Lakeer” investigates Chughtai’s quasi-autobiographical novel Tedhi Lakeer (1945) or The Crooked line through the extremely pertinent concerns of Gender and modernity. Rizvi posits the importance of the novel in “projecting the intellectual history of progressive ideals” taking root in the Indian subcontinent in particular, with respect to major spheres of human occupation such as education, politics, nation and nationhood, religion, psychology and so on.

This volume also reproduces voices of Chughtai’s contemporaries. Like Qurratulain Hyder in “Lady Changez Khan”, Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s “The ‘Sex Appeal’ of Ismat Chughtai’s Language”, Krishan Chander’s exposition of the ‘elusiveness of the ordinary’, Upendranath Ashk’s “The Dozakhi Ismat Chughtai” to name of few, all translated from Urdu to English. The two highly entertaining, perceptive and no-holds-barred interviews of Chughtai included in this volume are by Carlo Coppola and Asif Aslam Farrukhi. Chughtai’s persona and unconventional views emerge vividly and in all their glory: For instance while speaking to Farrukhi, she doesn’t bat an eyelid while placing Khwaja Ahmad Abbas in the league of herself, Manto, Chander and Bedi, saying, “I don’t measure people by the length and breadth of their writing. If somebody has written one good story, I believe in him…whatever (Abbas) has written is of a high standard.”

Talking about “Lihaaf” she proclaims unequivocally, “…(Never) have I written anything pornographic….The real dirt is in their minds.” Jalil’s An Uncivil Woman presents a carefully curated set of pieces ostensibly to rectify the relatively small space she accorded to Chughtai in her earlier work on the Progressive Writers Association. The essays herein seek to reveal both the staunch ideologue and the thoroughly rebellious persona of Chughtai which defied all labels through a rare combination of utter simplicity, and a searing, nuanced exploration of the other half of humanity.

The reviewer teaches English Literature at a Delhi University college