Cox's Bazar is a beautiful place but it is also fragile, facing environmental threats and refugee influx. Both Bangladesh and India will have to fight these challenges together

Recently, this writer was invited to participate in the ninth round of the Bangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue, a meeting of young minds, ideas and leaders from the civil, political and intellectual spaces. Supported by both Governments, this dialogue has become a keystone of bilateral relations. The present dialogue assumes significance in the wake of our eastern neighbour preparing itself to celebrate the “Mujib Year” from March 17, 2020 to March 17, 2021, to mark the centenary year of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father of Bangladesh and the father of the current Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina. Dhaka will also be commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Bangladesh Liberation, following the 1971 war between India and Pakistan.

Most leaders in Bangladesh have not forgotten the sacrifices made by the Indian armed forces during the 1971 war, where almost 2,000 Indians died on their soil. Such was the surge of emotion that cries of ‘Joy Bangla’ filled the streets of Kolkata back then. It is also a good time to remind the world of the genocide carried out by the Pakistani Army and their Razakar allies on a million Bengalis, both Hindus and Muslims. They were killed with the approval of the Pakistani State and the likes of General Niazi and Yahya Khan, who never paid for their crimes. All said and done, the “war” cannot and should not define the relationship between the two nations, particularly since half the population of both nations is under the age of 35. For most young Indians and Bangladeshis today, relationship between the two countries is primarily defined by cricket. The ongoing Test series is an evidence of that, with Bangladesh being the first nation to be hosted by India as the former learns to play Test cricket under the floodlights.

India’s ties with Bangladesh are also significant in terms of trade, which touched $10 billion last year. Even though it is highly skewed towards India — in a 9:1 ratio — Bangladesh’s largest item of import from India is cloth and yarn, which has powered that nation’s huge exports of ready-made textiles across the world. India also imports several of Bangladesh’s industrial and agricultural items. Our neighbour in turn relies on our agricultural produce. So India’s sudden ban on the export of onion, after a price spike back home, has become a major stumbling block to furthering relations between the two countries. If Indians thought that a 1,000 per cent increase in onion prices was bad, prices for the same crop have gone up 3,000 per cent in the neighbouring country, where the Government has resorted to airlifting onions.

But crises like onions, the occasional border skirmish and issues surrounding the sharing of waters from the Teesta river cannot hide the remarkable progress India has made with Bangladesh on the diplomacy and security front, particularly in joint-policing and intelligence efforts. And that has bolstered trade being conducted through waterways. Systems have been put in place at the Benapole-Petrapole border crossing, which have made customs clearances faster for trucks. New train crossings and services will smoothen trade further between the two nations. A recent deal to sell power to Bangladesh has eased the power situation in that country dramatically. India could use the grid in Bangladesh to send electricity to power growth in its own States like Assam.

However, there’s a lot that remains to be done such as simplifying border crossings — particularly in Meghalaya and Tripura — and facilitating trade to and from the North-east towards ports at Chittagong. There are also some contentious illegal immigration issues, particularly in India’s North-east, that need to be sorted.

India should also learn from Bangladesh, which despite being a poor country, has taken massive steps in meeting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals in education, sanitation and women’s health, leaving us behind.

There’s another front where Bangladesh scores well. Fishery management here allows it to manage and protect the Hilsa on its river system in a much better way than it is done in India, where the famed delicacy has been almost wiped to extinction. That said, India’s digital start-ups, with their expertise in several areas as well as access to global venture capital, can look at the Bangladeshi market with significant demand for online commerce. Indian airlines, too, can expand their services to Bangladesh where there is major demand for medical tourism. This is an attractive prospect for India’s burgeoning hospital chains.

The biggest learning from Cox’s Bazar was not the talks around trade or economic issues; it was the environment and refugee crisis. This picturesque city, with its massive 120-km long Inani beach, the longest sandy beach in the world, is a major draw for domestic tourists. Yet it is facing the brunt of the Rohingya refugee crisis.

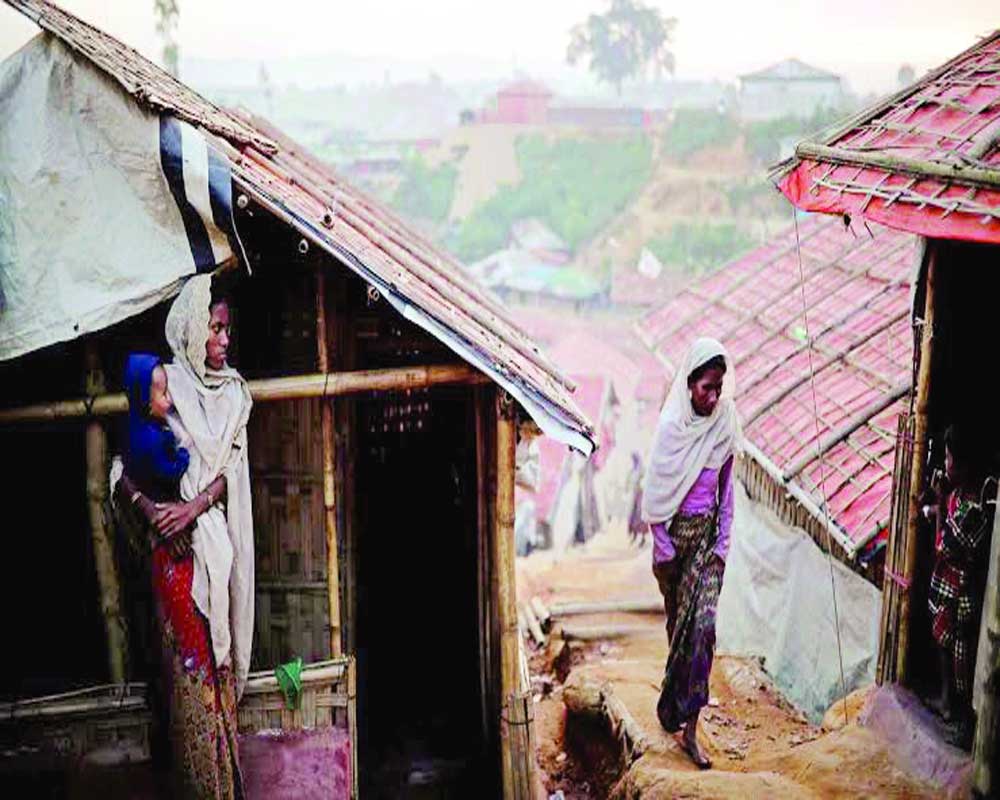

Local Member of Parliament, Asheq Ullah Rafiq, explained how the dramatic flow of over one million refugees across the Myanmar border overwhelmed this small town. Unprecedented brutality by the Army in Myanmar and the silence of Nobel Peace Prize winner, Aung San Suu Kyi, have left Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina with little choice. The main refugee camp at Teknaf has conditions described as similar to those of concentration camps. In smaller camps like those we visited, stories of women and child trafficking are rife.

Many of the issues surrounding the Rohingyas date back to historical times when the Rakhine Kingdom fought wars with the Bengal Sultanate for control of the areas in and around Cox’s Bazar. The anti-Bengali sentiment is still prevalent in Myanmar and even parts of India’s North-east. However, the refugee crisis will pale into insignificance before what is undoubtedly expected to happen in a couple of decades.

Inani Beach may be the longest beach in the world but the Bay of Bengal is claiming it back. On a drive between the hotel and the airport alongside the beach, giant sandbags by the roadside were a constant sight. Bangladesh is not only the most congested nation — its 160 million people are crammed into just 150,000 square kilometres. It is also one of the lowest-lying nations on planet earth. Even the city of Sylhet, pretty much on the border with Meghalaya, is barely 100 feet above the mean sea level. Global warming is a reality, one that we must accept, and it will eventually sink much of the lower Bangladesh and southern West Bengal. It’s evident not just on the beaches but even on a flight between Cox’s Bazar and Dhaka, where one crosses the mighty Gangetic delta. One can see the impact as the land is getting eaten away.

Bangladesh has faced some of the deadliest cyclones from the Bay of Bengal over the years as well. The simple fact is that people will have no option but to run away from the rising waters. But where will they run? Higher up the Gangetic plains into north India? It does not just end here. The rising tide will also push salinity levels up, making fresh water in all these rivers a luxury. A far inland Bihar could be rendered infertile by rising salinity levels, pushing refugees even further. In 1971, 10 million Bangladeshi refugees fled to India, to escape the murderous Pakistani Army. This put a massive strain on India’s more limited economic resources of that era. By 2071, which frankly is not that far away, there could be 10 times that number of displaced people streaming into India if we do not act to reverse the impacts of global warming today. And this is just considering the impact on Bangladesh. Given our coastal fragility, a similar number of internally displaced people will exist in our country.

The dystopian future with millions of humans crammed into highrise slums is not going to remain in the dreams of a Hollywood science-fiction screenwriter but as conditions in Teknaf show, humanity’s future will be very brutal. Yes, India and Bangladesh both have a moral imperative to lift millions out of poverty but that also includes doing something about global warming before it is too late.

(The writer is Managing Editor, The Pioneer)