Theresa May has described the Jallianwala Bagh slaughter as a ‘shameful scar’ on British-Indian history. It will heal only after Britain formally apologises for the crime

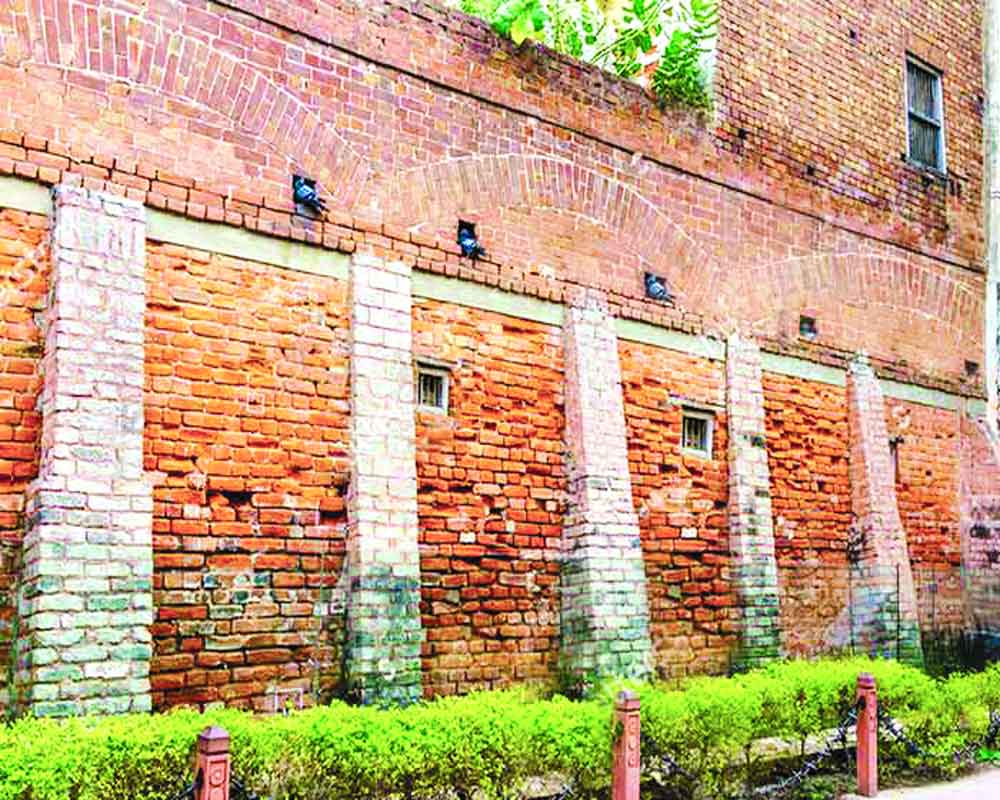

A hundred years ago this day occurred the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar, which remains one of the worst crimes of British imperialism in India. On that day, officiating Brigadier, Reginald Dyer, ordered Gurkha soldiers under his command to fire on a peaceful and unarmed gathering of men, women and children to celebrate Baisakhi. The firing continued for 10 minutes and was directed at places where the concentration of people was the heaviest.

The toll, according to official figures, was 379 killed and about 1,100 wounded. Unofficial — and by all accounts more correct — counts put the figure above 1,000 dead and 1,200 wounded. Outrage among Indians was countrywide and intense. Prominent among those expressing it were Pandit Motilal Nehru, Sir Shankaran Nair, who resigned his membership of the Viceroy’s executive council in protest, Punjab legislative council members, Nawab Din Murad and Karter Singh and, of course, Rabindranath Tagore, who renounced the knighthood conferred upon him by the British Government through an open letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, published in The Statesman (June 3, 1919) and Modern Review (July, 1919).

The letter, reflecting the deepest feelings of anguish and anger, began thus: “The enormity of the measures taken by the Government in the Punjab for quelling some local disturbances has, with a rude shock, revealed to our minds the helplessness of our position as British subjects in India. The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments, barring some conspicuous exceptions, recent and remote. Considering that such treatment has been meted out to a population, disarmed and resourceless, by a power which has the most terribly efficient organisation for destruction of human lives, we must strongly assert that it can claim no political expediency, far less moral justification.”

Stating that the “accounts of insult and sufferings” borne by “our brothers in Punjab” and the universal agony and indignation aroused “in the hearts of our people” had been ignored by the rulers, who were possibly congratulating themselves for having taught the people a salutary lesson, he added, “This callousness has been praised by most of the Anglo-Indian papers which have in some cases gone to the brutal length of making fun of our sufferings, without receiving the least check from the same authority — relentlessly careful in smothering every cry of pain and expression of judgement from the organs representing the sufferers.”

Finally, declaring his decision to renounce his knighthood, he had stated, “The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen, who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.”

The stray attacks, including that on a woman English missionary, that preceded the Jallianwala Bagh massacre had its roots in the agitation against the draconian Rowlatt Act (1919) — ostensibly aimed at squashing sedition. It turned British-ruled India much more of a surveillance-cum-police state than it had ever been. In protest, Mahatma Gandhi called for a nation-wide strike which drew an overwhelming response. In Punjab, the movement peaked in the first week of April when rail and telegraph services were disrupted. The Punjab Government, headed by the Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Michael Francis O’Dwyer, imposed martial law to maintain order and sought to teach the people of the province a lesson. The massacre followed.

Shamefully, the horror did not end with it. On the following day, Dyer issued a public statement in Urdu in which he asked (in English translation) the residents of Amritsar whether they wanted war or peace. If they wanted war, the Government was prepared for it. If they wanted peace, they would have to open shops and markets. Otherwise, they would be shot.

Next came a most humiliating measure, which lasted from April 19 to 25, 1919. From 6 am to 8 pm every day, people traversing the street on which the woman English missionary was attacked had to crawl on all fours for the entire length. Even doctors were not allowed to enter the street and the sick went unattended.

The mass murder and the threats and measures that followed were emblematic of the merciless exploitation and repression that characterised British rule in India under the camouflage of discharging its benign imperial mission of making this country fit for self-rule. The fundamental goal of the imperial Government was exploiting to the hilt India’s resources for Britain’s benefit. The draining of India’s wealth, which reduced the country, once celebrated for its prosperity, to utter poverty, has been exhaustively documented by Romesh Chunder Dutt in his classic, The Economic History of India, in two volumes.

Coming to specifics, Madhusree Mukerji has shown in Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II, how British policies led to frequent famines in India from the second half of the 18th century to 1943 when between 1.5 to three million people died during the Great Bengal Famine which was primarily caused by the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s cynical measures.

A number of Britishers, including Edwin Samuel Montague, secretary of state for India, criticised Dyer. But he also had his staunch supporters, including Rudyard Kipling and remained a hero to Colonel Blimps and allied circles. He was, by way of punishment, relieved of his command, denied promotion, made to retire prematurely and barred from further employment in India. This when he should have at least been cashiered and prosecuted for mass murder.

Michael Francis O’Dwyer, who fully supported Dyer’s action, was assassinated in London on March 13, 1940, by the fearless revolutionary, Udham Singh, who made no attempt to escape after the shooting and told the court during his trial that he was happy for what he had done and was not afraid of death. He ended by asking what greater honour could be bestowed on him than death for the sake of his motherland.

He was executed by hanging.

PS: British Prime Minister Theresa May has described the mass slaughter as a “shameful scar” on British Indian history. She should know that the scar will heal only after Britain formally apologises for the crime, which it has not done.

(The writer is Consultant Editor, The Pioneer, and an author)