Several committees and commissions have emphasised the importance of the mother tongue medium. It is to be seen what comes of it in the final education policy

The report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the 21st Century was released at the session of the International Bureau of Education (IBE) in Geneva on October 2, 1996. The chairperson of the commission, Jacques Delors, very clearly summarised the essence of global consultations and the future vision of global education in the 21st century. For individual national contexts, he unequivocally stated: “Education in every nation must be rooted to culture and committed to progress.” The report begins with Delors’s Preamble entitled, ‘Education: The Necessary Utopia’ and says it all in the first sentence: “In confronting the many challenges that the future holds in store, humankind sees in education an indispensible asset in its attempt to attain the ideals of peace, freedom and social justice.”

The report has been deliberated upon globally for over two decades; it has received global appreciation and has impacted policies and implementation strategies internationally. Its articulation of four pillars of education — learning to know, learning to do, learning to be and learning to live together — has received admiration from common folks to seasoned academics alike. In the first quarter of the 21st century, who would not appreciate the fact that education “is not a miracle cure or magic formula” but one of the “principal means available to foster a deeper and more harmonious form of human development and, thereby, to reduce poverty, exclusion, ignorance, oppression and war.” India, known for its economic, social, cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity, is committed to transform its education system to achieve social cohesion and religious harmony and strengthen unity in diversity. But its education system has to encompass a very sensitive canvas. Its three-language formula, accepted in the mid-1960s, is yet to be implemented fully in letter and spirit.

Its national policy on education was last revisited in 1992. After more than a quarter of the century, in 2019, the Kasturirangan Committee submitted the draft National Education Policy (NEP) to the Government for finalisation of a new education policy. The preparation of this report was preceded by a national consultation process spread over four years. The draft NEP is open for inputs and suggestions from every quarter before finalisation. It is interesting that widespread fresh consultations have generated demands for further extension of the time limit for submission of suggestions beyond July 31, 2019.

Yes, people are concerned about education, its quality, utility and capacity to achieve total personality development. While there is no limit to improvements in the presentation of such reports, one has to begin implementation at some point. The NEP, 2019 mostly consists of formulations that deserve support of all and active involvement of academics as well as scholars, who are unconstrained by ideological bonds and narrow political considerations.

The draft report attempts at giving a comprehensive view of national expectations and aspirations fully synchronised with international trends and requirements: “The vision of India’s new education system has accordingly been crafted to ensure that it touches the life of each and every citizen, consistent with their ability to contribute to many growing developmental imperatives of this country on the one hand and towards creating a just and equitable society on the other.” To achieve such an objective, the issue of ‘language’ and ‘medium of instruction’ will become relevant.

For obvious reasons, the British were not interested in educating Indians in their mother tongue. They needed obedient and loyal educated people who would despise everything that was Indian — be it culture, history or heritage. This could best be achieved by “delinking Indians from India.” The best and easily available tool was to develop fascination for English language and all that was Western and, hence, admirable. Under severe burden of learning an alien language, where was the time for children as also parents’ inclination to realise the importance of learning the mother tongue? It was rather interesting that within hours of the presentation of the report to the Human Resource Development Minister and its simultaneous uploading on the Ministry’s website, certain vested interests attempted to create an unsavoury conflict in the minds of people, raising the issue of the so-called imposition of Hindi on non-Hindi speaking States. It must go to the credit of the Ministry of Human Resource Development that within hours of the issue emerging on the national scene, it issued a clarification that the Government has no intention to impose any language on any set of people unwilling to learn it. In fact, ever since the three languages formula was accepted by the Government and a commitment made to the nation, none of the Union Governments ever tried to impose any language hegemony.

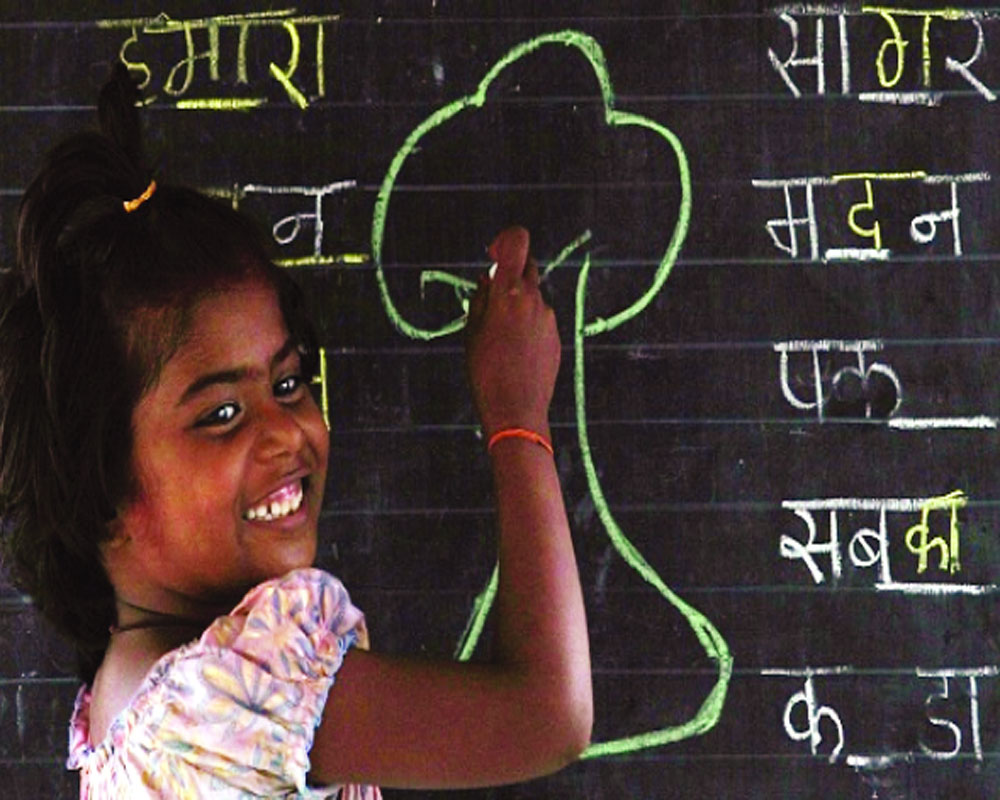

The issue of mother tongue medium has once again been comprehensively addressed in the draft NEP, 2019. It is a universally accepted fact that initial education must be provided in the mother tongue of the child. It is also a known that children in the age group of 2-8 years are extremely flexible in learning multiple languages.

The NEP report acknowledges: “Language has a direct bearing as the mediator in all cognitive and social capacities, including in knowledge acquisition and production. The science of child development and language acquisition suggests that young children become literate in (as a language) and learn best through (as medium of instruction) their ‘local language’ ie, the language spoken at home. It is interesting to note that the committee uses two terms — mother tongue and also the language spoken at the home.” One can cite an example that will indicate the farcical levels of fascination for English medium schools in India, particularly among those who can afford paying exorbitant fees in privately managed “public schools.”

A young professor, working in a national academic institution in Delhi, sought transfer to his home-town in Bengaluru to look after his octogenarian in-laws, who had no other support. The request was accepted and the family shifted to their home place “happily.” Their two kids — 10 and 12-year-old — got admission in a public school without any difficulty. However, their grandparents could communicate in Kannada only and the children were made monolingual, meaning they could speak English only. One had the occasion to ask the young parents how it was beyond comprehension that children were totally alien to Kannada. The response was very truthful and also revealing: “We decided to speak only English in our home and family conversation, even guests were requested accordingly. All this to ensure children acquire greater fluency in English — it was all for their bright future and to make their life easier to get a green card.” If highly educated people are so charmed by English medium and English language, none will be surprised to find the mushroom growth of English medium schools in villages and towns.

The growing fascination for English as the medium of instruction from day one onwards in schools is not new. It has a historic legacy. The language policy adopted by the British in India included every trick of the trade to wean Indians away from their culture and heritage and language was the first tool. One cannot ignore how Mahatma Gandhi analysed this fascination very early in his life.

On February 4, 1916, Gandhiji raised the issue of language and referred to the insight he had gathered from some Poona (now Pune) professors, who assured him “that every Indian youth, because he reached his knowledge through the English Language, lost at least six precious years of life.” On July 5, 1928, he made a very touching statement on the medium of instruction, which deserves to be re-read and examined in the context of language learning and policy formulation. In fact, more than the policy-makers, it is the parents who should be aware of the harm being inflicted on the children by forcing children to learn English at the cost of mother tongue language: “The foreign medium has caused brain fag; put an undue strain upon the nerves of our children; made them crammers and imitators; unfitted them for original work and thought; and disabled them for filtrating their learning to the family or the masses. The foreign medium has made our children practically foreigners in their own land.”

In his opinion, among the many evils that the British imperialists imposed on India and its people, the imposition of a foreign medium was the greatest. He fervently wanted India to shake itself free from the hypnotic spell of foreign medium; sooner the better. Sadly enough that was not to be. Practically every commission and committee appointed in the post-independence period accepted and emphasised the importance and necessity of the mother tongue medium but things have gone from bad to worse. We have reached a stage when Governments, having failed to look after schools properly, have allowed their credibility to touch the nadir. The failure to maintain the mother tongue medium, Government schools are now being covered under the plan called school merger. People understand the real position. It will be interesting to see what emerges on the language front and the issue of medium of instruction in the final national education policy.

(The writer is the Indian Representative on the Executive Board of UNESCO)