For an amicable settlement to this festering problem, it is essential for the country to move out of the bind that it has been in for the last several decades

The Supreme Court’s recent decision to appoint three mediators to attempt a solution through mediation of the vexed Ram Janmabhoomi issue in Ayodhya could be the last opportunity available to all parties to attempt an amicable out-of-court resolution of the vexed dispute that has been the perennial source of social disharmony. This mediation process will be a court appointed and court monitored exercise which will be conducted outside media glare “with utmost confidentiality”.

The idea of a mediated settlement in the Ram Janmabhoomi Case is not new. Two years ago in March, 2017, the then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, J S Kehar had suggested a negotiated settlement and had offered himself as a mediator. However, this proposal did not find favour with the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) and the Babri Masjid Action Committee.

This time around, objections if any are muted, probably because of the court’s determination to get all parties to the negotiating table.

The Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute has taken a torturous course, but some of the milestones in recent times are notable. The first of these was the Supreme Court’s judgement in Dr M Ismail Faruqui and others vs Union of India and others in October, 1994. In that case, the constitutional validity of the Acquisition of Certain Areas of Ayodhya Act, 1993 was challenged. The court upheld the Act but declared Section 4(3) of the Act to be invalid. This judgment resulted in the revival of all pending suits before the Allahabad High Court.

The second milestone is the sovereign commitment given by the Government of India in September, 1994, before the Supreme Court that if it was established that a Hindu temple or religious structure existed before the Babri Masjid, it would hand over the site to the Hindus. The Union Government had made a Presidential Reference under Article 143(1) of the Constitution in which it asked the Supreme Court “Whether a Hindu temple or any Hindu religious structure existed prior to the construction of the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid (including the premises of the inner and outer courtyards of such structure) in the area on which the structure stood”.

The Presidential Reference said the government proposed to settle the dispute after obtaining the opinion of the Supreme Court. In the course of the arguments when some litigants representing Muslims interests said the reference would serve no purpose, the court asked the Solicitor-General to respond. The Solicitor-General made a written submission on behalf of the Union Government in response to the court’s query and what was said therein on behalf of the government is significant. The government said it was committed to the construction of a Ram temple and a mosque, but their actual location will be determined only after the Supreme Court renders its opinion in the Presidential Reference.

The government made the following commitments before the apex court in that submission: That it would treat the finding of the Supreme Court on the question of fact referred to it in the Presidential Reference as a verdict which is final and binding; that consistent with the court’s opinion it would make efforts to resolve the controversy by a process of negotiation; that if a negotiated settlement is not possible, it would be committed to enforce a solution based on the court’s opinion. It further said that “If the question referred is answered in the affirmative, namely, that a Hindu temple/structure did exist prior to the construction of the demolished structure, government action will be in support of the wishes of the Hindu community. If, on the other hand, the question is answered in the negative, namely, that no such Hindu temple/structure existed at the relevant time, then the government action will be in support of the wishes of the Muslim community”.

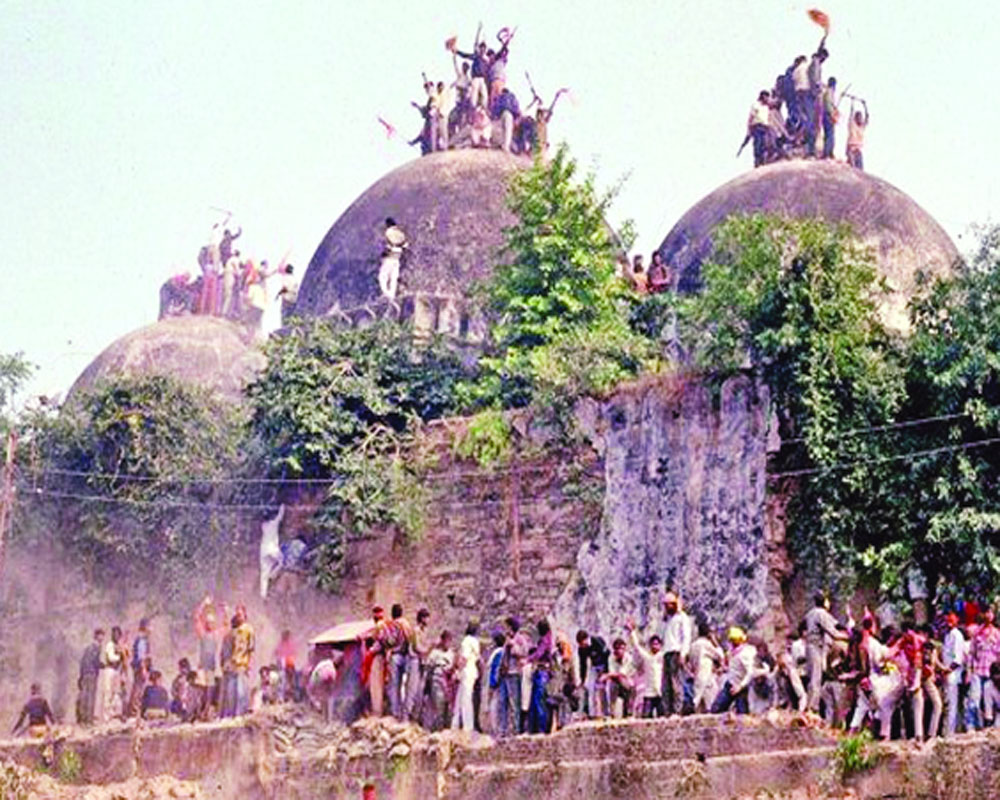

Why did the Union Government put this question to the Supreme Court. A white paper published by the Centre after the demolition of the Babri Masjid provides a clue. It said that during negotiations aimed at finding an amicable settlement, one issue that came to the fore was whether a Hindu temple existed on the site and whether it was demolished to built the masjid. Muslim organisations claimed that there was no evidence to prove this. Muslim leaders also asserted that if this was proved, “the Muslims would voluntarily hand over the disputed shrine to the Hindus”.

The Supreme Court declined to answer this question. The five-judge Bench which gave its verdict in the Faruqui Case in October, 1994 simultaneously disposed off the Presidential Reference. It said the reference was ‘superfluous and unnecessary and does not require to be answered”. However, the Union Government’s desire to secure an answer to the million dollar question was met when the Allahabad High Court, the pending suits before which got revived as a result of the Supreme Court’s order in the Faruqui Case, ordered the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to excavate the site and see what lay beneath the disputed structure.

The ASI, after extensive excavations, informed the court that there was evidence of a massive structure below the disputed structure which had “distinctive features found associated with the temples of North India”. Based on this finding, all the three judges on the Lucknow Bench of the Allahabad High Court concluded that a Hindu temple existed below the disputed structure. The Supreme Court has stayed this judgement after it was challenged by several parties to the dispute.

It is not unusual for courts to suggest mediation. This is often suggested by courts in many civil matters because there are no winners and losers when issues are resolved through mediation. However, if mediation fails, the court will have to hear the matter and arrive at a conclusion, which may or may not please all parties in a dispute.

Meanwhile, what will the Union Government do? It has committed itself to initially try and settle the dispute through negotiations once it heard from the Supreme Court on the question of fact it had put before it in the Presidential Reference. The court however declined to answer that question, but the observations made in the white paper and the ASI’s substantive report to the Allahabad High Court cannot be wished away.

The three mediators appointed by the Supreme Court — Justice Fakkir Ibrahim Kalifulla, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar and Sriram Panchu — will have all this material before them when they begin negotiations in search of an amicable settlement. All parties to the dispute will need to join this effort without hesitation in order to resolve the matter through mutual give and take. They must give mediation a chance.

(The writer is Chairman, Prasar Bharati)