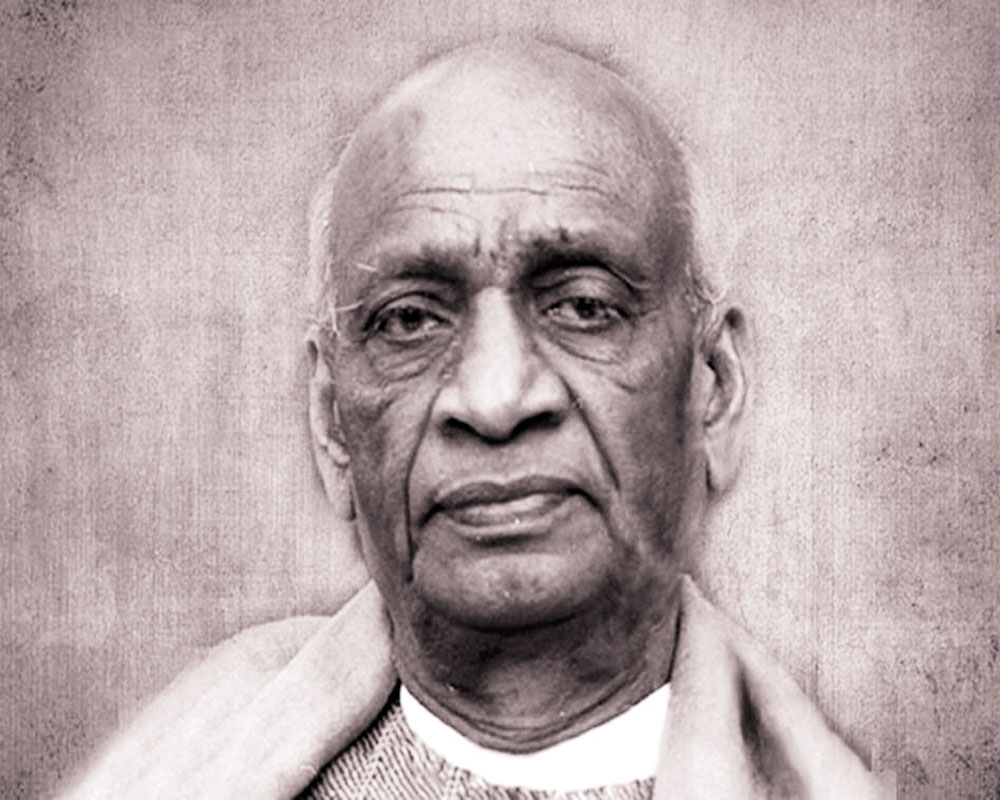

Hindol Sengupta’s book is a sweeping, magisterial retelling of Sardar Patel’s story and provides rare insights into the life and ideology of the man who brought in the vital pragmatism which held together the national movement and the first ideas of independent India. An edited excerpt:

2010 was a big year for the Gujarat Club in Ahmedabad. It was 122 years old and in desperate need of some repairs. It boasted 1,100 members but not many had bothered to get any spring cleaning done for years. But now a budget of Rs 75 lakh had been sanctioned and, among other things, two billiards tables were being imported from England. This club, after all, was where Geet Sethi, who won the World Billiards Championship three times as an amateur and six times as a professional and had two world records, had cut his teeth.

The last time the club got some repairs and spring cleaning done was 25 years ago when filmmaker Ketan Mehta wanted to shoot some scenes on the premises. Mehta wanted to portray the club as it would have been in June 1916, barely 28 years after its creation. The scene had barristers playing bridge under punkha who pulled giant fans to keep the place cool, and one of them getting progressively more irritated because of the disturbance caused by a political activist. “One of the card players, a barrister, was in winning form and in high spirits when the boy brought in tea. At that moment, someone dashed into the room to invite the players to meet a Gandhi and hear the lecture he was giving that evening. No one paid any attention. The players went on drinking tea, eating English-made biscuits and discussing their next rubber.”

The barrister was Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. We find him returned from England now, having finished his legal education and learnt to “buy some well-cut clothes”. He was now determined to be the star of a wealthy fraternity, which he thought was “pompous, status conscious”, but where he swiftly made a mark “with his domineering personality”. He now towered over the men who had intimidated him once upon a time when he was but a pleader. He was not only their equal as a barrister, often a more successful one at that, but he was also a better bridge player!

While he was a pleader, Patel’s family was in a financial crisis, which is apparent from a letter he wrote in 1904 to his brother Narsibhai. “I have written to return the money with interest and so you need not worry in the matter... you have written about the mortgage of sister’s ornaments that does not behove you. You have written that you are in debt. But I understand that your debt is my debt. So you write to me the names of creditors, so I will relieve you as quickly as possible from the debt so that you heave a sigh of relief.”

By 1916, he was on far firmer ground. One aspect of his personality as a barrister seems to have been “a firm and pensive expression, almost as if one looked down upon the world with a sort of superiority complex”. But attitude alone could not have brought Patel the success he saw as a barrister in Ahmedabad. He was also willing to take perilous chances, going so far as to chastising a judge for being prejudiced against people from his home region of Kheda. The astounded judge granted his client the bail that Patel wanted.

Barrister Patel, then, with his sturdy pragmatism had no time for soft-spoken, barely clad political activists, even if they were fellow barristers of considerable renown in South Africa. “I have been told he comes from South Africa,” Patel said when asked if he had met Gandhi. “Honestly, I think he’s a crank and, as you know, I have no use for such people.” On yet another day, when Gandhi’s arrival was announced at the club, Patel is said to have shouted out:

“Go away! We don’t want to listen to your Gandhi!”

But the astute lawyer had noticed something: This frail man spoke more like a sadhu than a politician. Why was a man who wanted to talk about greater freedom for India speaking of “the power of truth, which is the same as divine love”? What did divine love have to do with fighting colonial injustice?

He had also realised something else: Gandhi was gathering some clever people around him, people who had Patel’s admiration — DB Kalelkar, Narhari Parikh, Mahadev Desai, (Swami) Anand and KG Mashruwala. Of these men, Parikh and Desai were competent lawyers whose work Patel respected. What was it, he wondered, that was drawing men like these to this Gandhi?

Patel was 42 years old when he met Gandhi, who by then was 48. The age difference between the men was barely six years. Compared to this, Nehru was 20 years younger than Gandhi — it is easy to see how the Gandhi-Nehru relationship would be paternal. It is also easy to see how the relationship between Patel and Nehru could have transitioned (or even veered) from familial to rival, for aren’t siblings ever so often rivals?

Three key relationships had an abiding impact on the founding of modern India, those between Gandhi and Patel, Gandhi and Nehru, and Nehru and Patel. Of these, the most layered and subtle was the relationship between Gandhi and Patel. Patel, like everybody else, called Gandhi Bapu, but the relationship was more intricate than a simple familial tie. Patel had been brought up to respect his elders, especially his elder brothers. Even though when he had first saved up money with great difficulty and prepared his papers to go and study law in England, his elder brother Vithalbhai had cheated him out of the chance. The papers came in the name of VJ Patel, which were the initials of both brothers, and “exercising an elder’s prerogative... Vithalbhai took it to be his opportunity first—not the younger brother’s, no matter if the latter had sweated to save money for this visit. Not only did he surrender his travel documents to Vithalbhai, but also willingly agreed to bear his entire expenses”.

Patel refers to his relationship with Vithalbhai in a speech in March 1921: “He [Vithalbhai] told me: ‘I am your elder brother and I should go first. You may get an opportunity after I return, but if you go first, I would never have any chance of going abroad.’ I went to England after the return of my brother three years later. After I had returned, we two brothers decided that if we wanted Independence, we would have to turn into ascetics and serve the country without any thought of self. My brother then left his roaring practice and engaged himself in the service of the country. The looking after of the family fell on my shoulders. The good work was for him and the inferior enterprise was for me.”

This anecdote about Patel is not one of the more popular ones. In fact, it is not even the first thing that comes to mind when one thinks of Patel, the Iron Man of India. But I believe it is indicative of a pattern in Patel’s life, of an occasionally misguided sense of duty that haunts critical points of his public life and journey as a leader. As we shall see, this relationship with Vithalbhai would also guide one of his biggest battles within the Congress Party — with Netaji.

It certainly could be, as we will see in this book, a metaphor for a part of his intricate relationship with Gandhi. What did Patel expect of Gandhi, and indeed what did Gandhi expect of Patel? As one of Gandhi’s earliest and most formidable lieutenants, Patel was, in a sense, the bad cop to the good cop played first by Gandhi and then by Nehru in the Indian freedom movement. Some writers have painted Patel as the villain in the dispute between Netaji and the Indian National Congress, and finally Bose’s breakaway from the Congress, claiming that: “So fond of Bose had Vithalbhai become that he willed a portion of his fortune to him to be spent for the ‘political uplift of India and for publicity work on behalf of India’s cause in other countries’. But the will was challenged by Vithalbhai’s sibling, Vallabhbhai Patel as a consequence of which Bose didn’t receive a penny.”

Excerpted with permission from Hindol Sengupta’s The Man Who Saved India: Sardar Patel and his Idea of India, Penguin Random House, Rs 799