Who Will Defend Gandhi?

A society must periodically ask itself an uncomfortable question: who deserves respect, and why? Is respect owed by identity alone, or is it earned through conduct, contribution, and moral example?

Respect is not automatic. It is earned through behaviour, values, and contribution, not granted simply because of age, gender, or status. At a collective level, societies choose to honour individuals who enrich public life, strengthen moral conscience, or fill an ethical void.

This is why certain figures are elevated as ideals. They embody values many admire but often struggle to practise. Indian civilisation has long recognised such figures, from Shri Ram, revered as Maryada Purushottam, to Buddha, Mahavir, and Guru Nanak. Over time, new names join this moral lineage, shaping ethical thought across generations.

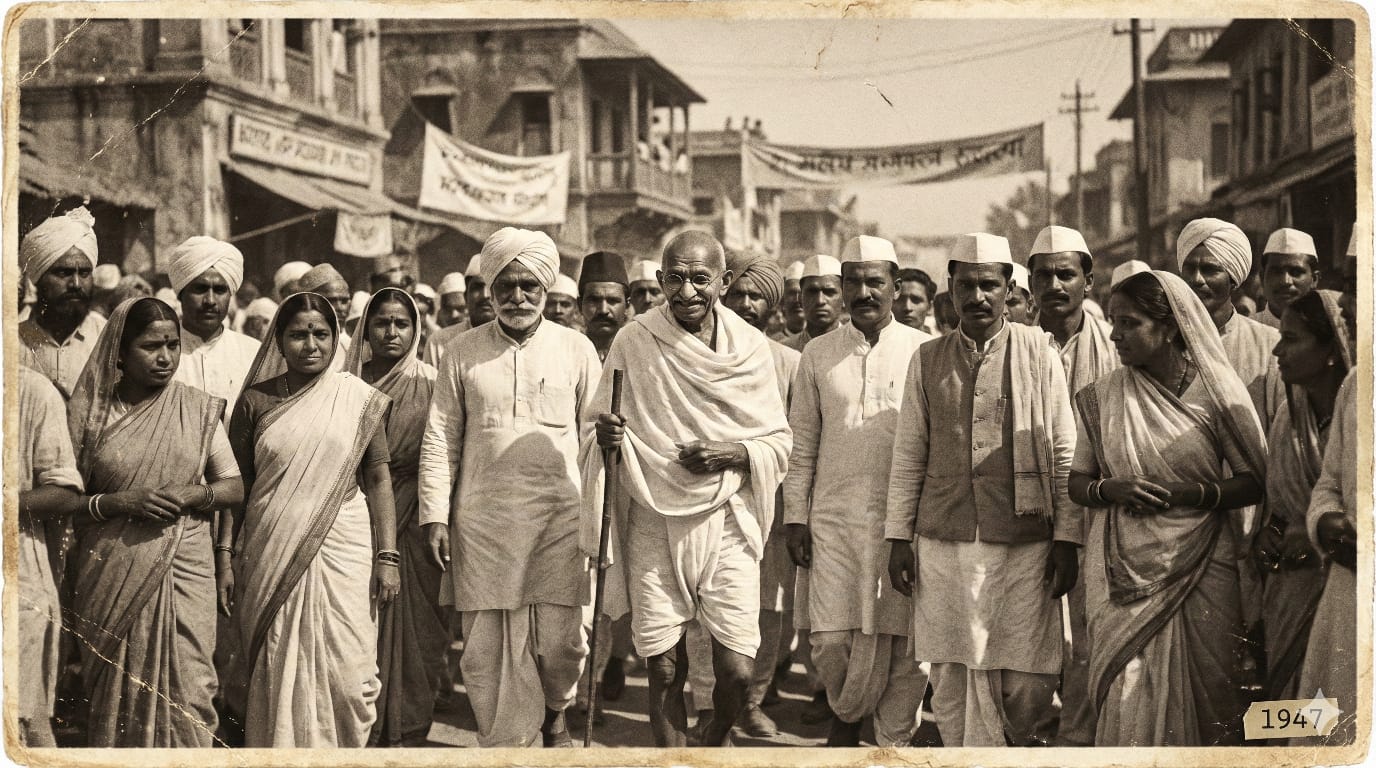

In the twentieth century, one such figure was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

There is ample space for debate about Gandhi’s ideas, strategies, and decisions during the freedom movement. Criticism is not only legitimate but essential in a democracy. No individual is beyond scrutiny, and no historical figure is free from error. Gandhi’s insistence on moral purity and nonviolence, often described as moral absolutism, can and should be critically examined. At times, this rigidity may have constrained political flexibility or failed to address urgent ground realities. These concerns deserve serious engagement.

However, acknowledging these limitations does not justify reducing Gandhi to a caricature or subjecting him to personal abuse. Debate is meant to illuminate complexity, not erase legacy. The response to ethical rigidity must be ethical discussion, not ethical vandalism.

Recent efforts by the government and public commentators to foreground the contributions of other freedom fighters are welcome. Leaders such as Sardar Patel, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Jayaprakash Narayan deserve far greater recognition than they once received. Earlier political narratives often centred excessively on a few personalities, and correcting that imbalance is both necessary and healthy.

But this correction should not come at the cost of diminishing Gandhi. He did not declare himself the Mahatma; history and the world did. His global stature rests on ideas that influenced civil rights movements far beyond India. Acknowledging others does not require tearing down one individual.

Great individuals are not remembered because they were flawless. They endure because their virtues outweighed their failings, and because they grappled with their limitations in ways that inspired social change. Ideologies can be questioned, accepted, or rejected. But selectively highlighting personal shortcomings while ignoring the larger moral contribution distorts both history and intent.

Today, in an age of instant information, negativity surrounding public figures often travels faster than careful assessment. Algorithm-driven platforms reward outrage, while nuance struggles to hold attention. In this environment, facts are frequently presented in fragments, stripped of context, or selectively emphasised to provoke reaction rather than understanding. It is always easier to identify ten flaws than to engage honestly with ninety virtues. This does not mean flaws should be ignored; they must be examined in proportion and context, not weaponised to discredit an entire legacy.

Gandhi’s ideas may not offer ready answers to every contemporary challenge. Some of his views may appear outdated or impractical. His approach to maintaining harmony between Hindus and Muslims during a deeply fractured period remains open to debate, particularly where he is perceived to have placed a greater moral burden on Hindus in the pursuit of peace. These questions merit serious historical and political examination.

The Partition of India, however, is increasingly discussed in narrow and oversimplified terms. There is a growing tendency, especially among younger audiences, to attribute this complex tragedy to a single individual, ignoring the broader colonial, political, and communal forces that shaped it. Such reductionism weakens historical understanding rather than strengthening it.

A similar simplification surrounds Gandhi’s commitment to nonviolence. Rooted in traditions articulated by Buddha and Mahavir, Gandhi’s nonviolence was not merely a moral position but a strategic response to colonial rule. Yet it is often dismissed today as ineffective or portrayed as weakness, despite historical evidence of its role in mobilising mass resistance and challenging British authority. His methods and ideas can be debated, refined, or rejected, but not casually dismissed.

Concern arises when legitimate critique slips into distortion. Portraying Gandhi as a figure who deliberately misled the nation, or invoking his assassin as a point of comparison, reflects a deeper unease in how history and moral leadership are being revisited. When Nathuram Godse attracts more attention than Gandhi on occasions such as Gandhi Jayanti or Shaheed Diwas, it signals not a careful re-examination of ideas, but a shift in public focus away from engagement and towards ideological assertion.

A society that cannot respect its own ideals risks losing the ability to create new ones. Yesterday it was figures like Savarkar, Hedgewar, and S.P. Mukherjee; today it is Gandhi, Nehru, and Ambedkar; tomorrow it may be Vajpayee, Modi, or Manmohan Singh. Every leader will have flaws. If public discourse is reduced to character assassination rather than critical engagement, no ideal will endure long enough to guide the collective conscience.

Gandhi would not have wanted laws to shield his reputation. He believed ideas must defend themselves through reason and moral force. Yet the question remains whether Indian society and the state should reflect on how national leaders are remembered, just as we collectively insist on dignity for women, elders, and parents despite their human imperfections.

Who, then, will defend Gandhi? Perhaps the more pressing question is whether we are prepared to defend the idea that moral leadership, however imperfect, still deserves respect.