When GDP met IIP, with CPI, income tax, and GST as bridesmaids

Some politicians are destined not to attract flamboyant attention. Nirmala Sitaraman, the finance minister, falls under this category. Indeed, she is known to complain to friends that she never gets the credit, whether it is related to how she admirably handled the economy during the pandemic, and post-Covid period, and how she put more money in the pockets of firms, and individuals through lower taxes and GST. One can argue about her actions but she has emerged as one of the most competent FMs in this century.

Sitaraman projects the Modi regime’s viewpoints, and announces reforms that were considered tough, if not impossible, a few years ago. This year was possibly the one when she put her best foot forward and, mind you, she has big strides. She may seem like a contradiction as she passed out from JNU, espouses right-wing ideology, and was considered ‘Her Master’s voice.’ But she became her master, transformed from a lightweight to heavyweight, and gained respect. Look at the giant steps she took this year.

The FM raised the personal income tax exemption limit to INR 1,00,000 a month, or INR 12,00,000 a year. These are phenomenal numbers, if one considers that the annual per capita income is around INR 2,00,000. This implies that the bulk of earning citizens walked out of the tax net. It is another thing that Sitharaman smartly kept open the doors for them to voluntarily walk into the net later. The caveat is that an individual needs to file annual returns to claim the 10 per cent tax refund that is deducted at source.

In effect, the taxpayer, or the non-taxpayer, gets into the official database, and needs to pay taxes later when the annual income goes beyond INR 12,00,000. The FM slashed corporate taxes a few years ago to encourage investments, and uplift the Make-in-India campaign. Sweeping reforms in the GST regime reignited consumer sentiments that were weak since 2021. Given the contradictions that surround Sitharaman, it was inexplicable that the country’s GDP grew by an unbelievable eight per cent in the first half of this fiscal.

Remember this was the period when experts claimed that consumer buying remained subdued, growth was expected to slow down, American tariffs had kicked in, private investments were down, and stock markets were wary due to limited corporate earnings. GST revived buying and spending but reduced Government revenues. Real GDP growth was excellent, but nominal growth, on which fiscal deficit is calculated, was on the lower side. But this was typical of Sitharaman’s tenure as the FM since 2019. She has worked in an era of unprecedented crises, which came one after another.

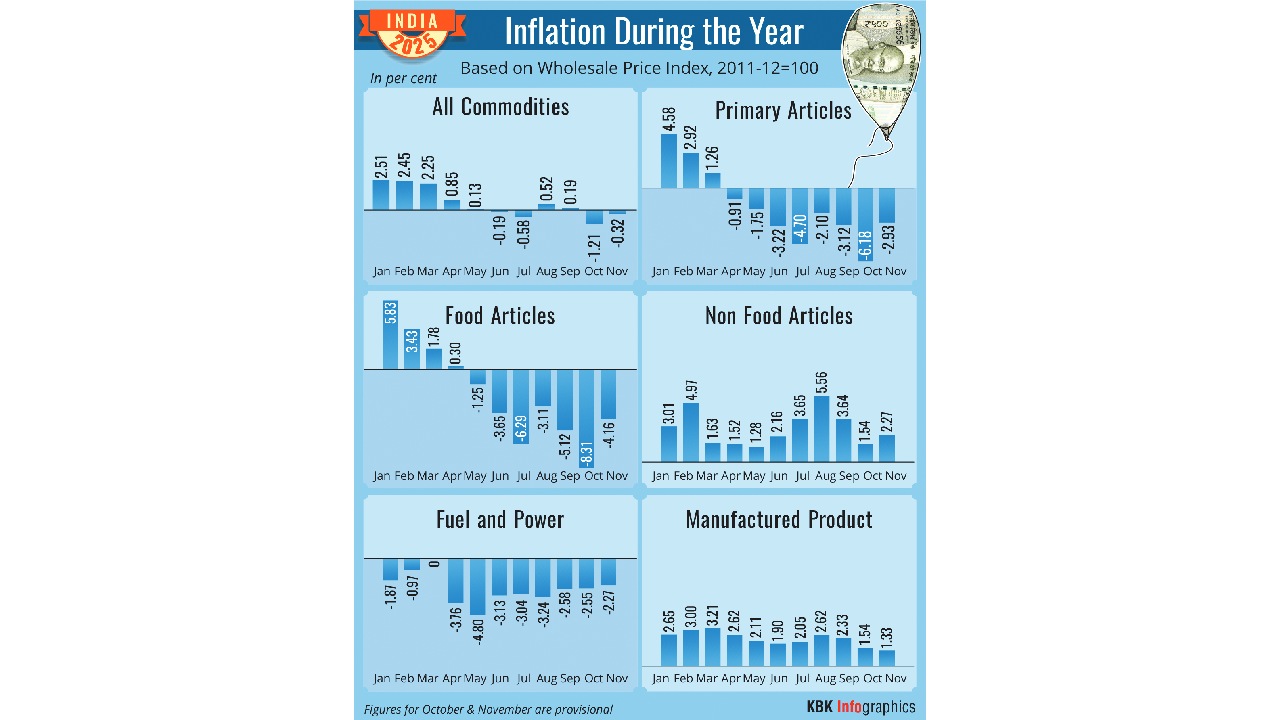

Yet, the Indian economy, which was believed to flatter to deceive, possibly continues to flatter with less deception. Or so one may believe. In the recent past, the Index of Industrial Production showed meagre growth, and the core sectors seem unhealthy. The stock markets remain unexcited about GDP growth, but there may be other factors responsible for it (See the article on stock markets). In addition, inflation is down, negative for food grains, which was unheard of, or nearly unheard of. Prices in this country have their own minds, and can shoot up within weeks and months.

Hence, Sitharaman may still not get the credit due to her. There are, and will be, questions raised about her ability and credibility, especially if the economy lurches into other crises in 2026. She will find it hard to convince critics, especially in an ideologically-polarised nation. Nothing epitomises this better than the new labour rules. After years of passing the four laws, they were codified this year. Now, one hopes that manufacturing will get another boost, and India will begin to rival China, South Korea, and Vietnam. Of course, the destination is still a long way off, and there are miles to go.

Maybe it will be another FM, who will be heralded for the achievement years later. By then, Sitharaman may be forgotten, just like other FMs were. Not to forget, there are many slips between the cup and the lip, thanks to red tape, bureaucracy, and rent-seeking, which are rampant in India. Overall, 2025 denotes a success story for the economy. High GDP growth, higher than estimated, at least till the first half, ridiculously-low inflation, lower taxes, record farm output, amazing rise of the services sector, and Government spending may enthuse private investments, and manufacturing.

Critics will decimate such ideas, and claim that the numbers are cooked. But she has lived in pressure-cooker situations ever since she became the FM. Before that, she was the BJP’s spokesperson, and was constantly eschewed by the media. Moreover, when onions prices went up, her comment was astounding. She said that she does not eat onions. So, while one can question her kitchen cooking, or eating habits, one is not sure if the same applies to data-cooking, since the hot-potato figures are handled by the other departments.

In this ephemeral jungle of numbers and data, everything is sacrosanct, and nothing is. Politicians deal in contradictions, and many love to do so. The ruling regime repeatedly announced that it believes in minimum Government, maximum Governance, and then the prime minister announced that the regime created tens of thousands of government jobs. GDP growth sizzles, even as firms are out in the cold. Inflation is down but people complain about prices. GST rates are slashed, but refunds are taken out of the equation.