India likely to grow at 7.5-8%: CEA

Sounding an overall optimistic note about the Indian economy, which includes a medium-term growth potential that has strengthened to seven per cent, and a “benign” inflation outlook, the Economic Survey (2025-26) highlights key areas of reforms, and inherent weaknesses and challenges that plague crucial areas. The issues that require attention include manufacturing, exports of products, stability of the rupee, and problems in sectors like insurance.

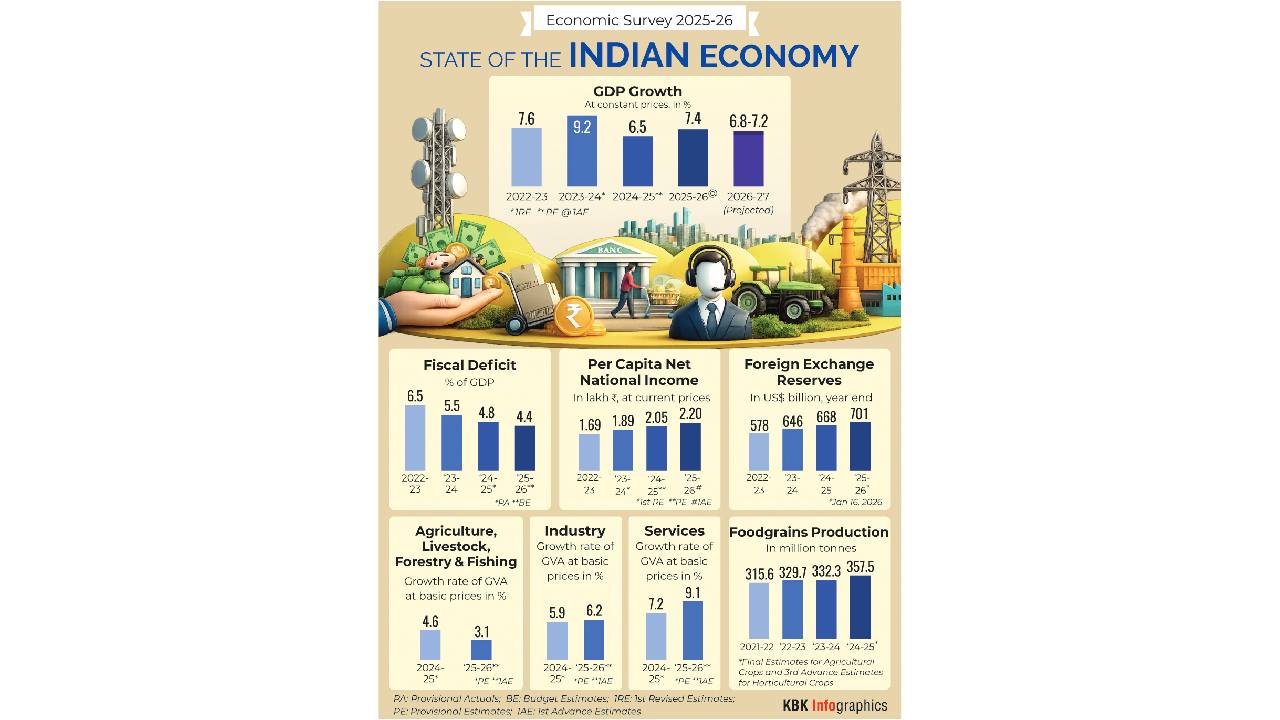

While growth is expected to slow down to 6.8-7.2 per cent in 2026-27, compared to an estimated 7.4 per cent in 2025-26, India’s potential growth rate can be at least seven per cent, and even jump to 7.5 per cent over the next few years. The trick will be to bolster manufacturing, exports, and process reforms.

“If we are able to achieve manufacturing and export competitiveness, and pursue further process reforms in the areas of land and cost subsidisation, and bring down the cost of manufacturing, the potential seven per cent growth can even rise to 7.5 per cent and eight per cent in the next few years,” said A Anantha Nageswaran, the Chief Economic Advisor (CEA) who wrote the Survey’s preface, in a media interaction after the document was tabled in Parliament.

Industry associations agreed with the growth predictions. “CII concurs with the Survey’s assessment of India’s growth outlook, with the projected growth… appearing realistic amid global uncertainties, and external headwinds. It is our sense that with moderate level inflation, we can be looking at double-digit nominal (as opposed to real) growth,” said Chandrajit Banerjee, director general, CII.

Of the three sectors, agriculture trends reflect “structural characteristics,” as the growth in crop segment, which accounts for more than half of the value added, is “marked by significant year-to-year variability, and has not exhibited a sustained upward trend. This reflects limited productivity gains.

Luckily, allied activities like livestock and fisheries have grown at stable rates of 5-6 per cent. Although there is no decline in the contribution of manufacturing, whose value added is up to over six per cent in this financial year, its share remains “steady” at 17-18 per cent, and the gross value of output is “stable” at 38 per cent.

This may be a matter of concern as manufacturing is the key to upgrading India’s standing as a global economic superpower. It is manufacturing that can aid exports.

However, the Survey warns about “one wrinkle in the ointment.” The paradox of 2025, it states, is that “India’s strongest macroeconomic performance in decades has collided with a global system that no longer rewards macroeconomic success with currency stability, capital inflows, or strategic insulation.”

India’s economic ambitions will, therefore, confront “powerful global headwinds.” But taking a positive note, the Survey states, “These same (headwind) forces can be turned into tailwinds if the State, the private sector, and households are willing to align, adapt, and commit to the scale of effort that the moment demands. The task will be neither simple nor comfortable, but it is unavoidable.”

The Survey sketches three global scenarios for 2026 (calendar year). The best-case one, with 40-45 per cent probability, is that 2026 will be “business as in 2025, but one that becomes increasingly less secure, and more fragile.” The margin of safety will thus be “thinner,” and “minor shocks can escalate into larger reverberations.”

In the second scenario, with a similar 40-45 per cent probability, policy will become national, and nations will face “a sharper trade-off between autonomy, growth, and stability.” In the third one, with 10-20 per cent possibility, there is a risk of a “systemic shock cascade,” whose macroeconomic consequences may be “worse than those of the 2008 global financial crisis (Great Recession).”

On the positive side, low inflation will continue, and the outlook seems benign, “supported by favourable supply-side conditions, and the gradual pass-through of GST rate rationalisation.” The problem is that while consumer inflation is down to 1.7 per cent, due to better farm conditions, and corrections in the prices of vegetables and pulses, core inflation has “exhibited persistence.” However, the Survey contends that the latter is due to price spikes in precious metals (gold and silver), and if adjusted for them, “underlying inflation pressure appears materially softer,” with limited overheating.

Unemployment is down over the first three quarters of this financial year, from 5.4 per cent in the first quarter to 4.9 per cent in the third one. India’s poverty rate is just above five per cent, with another nearly 24 per cent for lower-middle-income poverty. But these figures are not comparable to the earlier poverty lines.

The current global order, states the Survey, faces three challenges, which include trade policy uncertainty, strategic decoupling among major economies, and migration of national security into the trade domain. Couple this with the geopolitical realignment, as supply chains are evaluated as per strategic autonomy, not cost efficiency. Nations “exercise greater caution regarding who they trade with, how they source inputs, and which partners they depend upon.”

This is why manufacturing and manufacturing-driven exports are crucial. India’s exports depend on goods that “fall into low- and mid-complexity categories” such as petroleum, medicines, rice, and diamonds. The nation needs a “significant structural shift towards high-complexity categories” like electronics, precision engineering goods, and high-value services. In electronics, India has made huge strides, as exports in this segment grew by more than 35 per cent year-on-year between April and December 2025.

The fate of the rupee, which has tumbled in the recent past, is linked to merchandise exports. Cross-country experiences show that durable currencies are grounded in the “gradual build-up of export capabilities, particularly in manufacturing.” For India, “this implies that improving medium-term exchange rate outcomes is inseparable from building a strong and competitive manufacturing base anchored in export growth.” They remain the reliable channel for productivity gains, scale economics, and global demand for Indian products.

Reforms are crucial. GST still needs re-imagination, and policy design must rely on “trust-based, and technology-driven compliance models.” Although expenditure on subsidies is down as a percentage of GDP, and direct benefit transfers have rooted out corruption and wastage, there is scope for improvement. Cross-subsidies in railways between freight and passengers need to go. “High freight rates… distort competition with roads, inflating… prices, as well as logistics costs.” The same is true of the power sector, where domestic users pay below costs.

In sectors such as insurance, which are crucial for citizens, there are miles to go. Insurance is saddled with high costs, which results in a paradox. Insurance density has risen, which means better spending by households, but “penetration has stagnated and declined to 3.7 per cent. This paradox indicates that while the sector is successful in deepening revenue from existing customers, high distribution costs are preventing a widening of the risk pool.” (With PTI inputs)