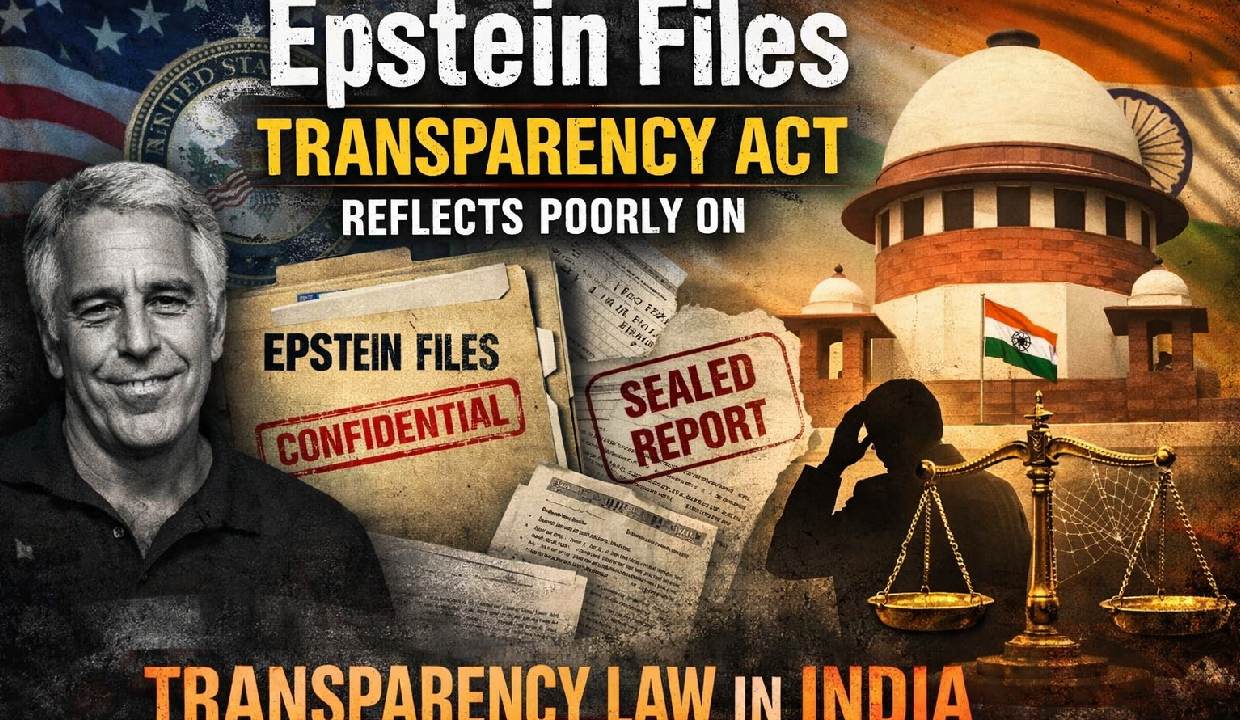

Epstein Files Transparency Act reflects poorly on transparency law in India

Epstein Files is a case of absolute systemic failure of administration of law and justice in the USA, but it is equally a case of unprecedented legal jurisprudence on transparency, which we Indian lawyers enviously look at, given our track record on transparency in the judicial system in our backyard.

Many Indians don’t know that the Epstein Files is judicial record and not some media scoop. It is released by the Department of Justice of the USA in compliance of a law Epstein Files Transparency Act, passed by the US Congress and duly signed by Donald Trump on 19th November 2025, when he himself is one of the thousands of powerfuls finding appearance and reference in the crime files of convicted Sex offender Jeffery Epstein.

The law was passed under pressure from public-spirited people and political opposition owing to extraordinary public interest involved in the case, as it was important to release the information pertaining to the case as to who all were involved or complicit, since the case involved worlds who.

The object was to showcase transparency, whether the law and justice of the country functioned with fairness, considering the rich and powerful involved in the case. The Transparency Act is a landmark case of balancing out the right to Privacy & Right to Reputation vis a vis public interest.

It’s more of a marvel given the fact that the release involves names of eminent persons across the globe and therefore it periled diplomatic relations and transgressed the boundaries of domestic law.

In contrast, in India, “the transparency law” of India- The Right to Information Act has been interpreted in a manner insulating the Supreme Court for a very long and there’s lots of opaqueness which is yet to be light holed.

The Supreme Court didn’t make the indictment report of Justice Yashwant Varma regarding burnt cash found at his Delhi bunglow in March last year.

It eroded the Public Trust in the judiciary gravely and the secrecy in which it was dealt by the Supreme Court injured the faith in the judiciary more than the alleged scam itself.

He is yet to be impeached. It is only after this alleged cash scam that the Full Court of the Supreme Court passed a resolution mandating Supreme Court judges to disclose their assets to the public, following which only 24 judgesout of 33 judgesthen declared their assets.

However, in High Courts, the declaration of assets is still voluntary and hence very little compliance.

The SIT report in Reliance Foundation’s Vantara case was sealed and only a summary of it was made public.

The case involved allegations of illegal procure mentof wild life in contravention of various laws and financial impropriety by the Foundation.

In 2009, Madras High Court judge R Raghupathi had alleged in open court thata Union Minister, through a lawyer, approached him to influence him in a case being probed by CBI.

When an RTI activist sought the pertaining correspondence between Justice Raghupathi and the then CJI, the Central Public Information Officer of the Supreme Court denied this information, saying that it’s not available with the Supreme Court Registery.

It’s noteworthy that the office of CJI was held to be under RTI only in 2019 in a judgment after a long legal battle, raising hopes that it will cut through the opaqueness which pervades the judiciary. Even there, the Court held that RTI is not absolute and it has to be balanced with the right of privacy of judges.

These incidences reflect poorly on the transparency law in India, especially when it comes to the judiciary and the administration of the judiciary. And had we had a case like Epstein here, we could only look gaping towards the heavens.

Writer is a lawyer practicing at the Supreme Court; views are personal