Debate intensifies: As impeachment motions yield few results, can the Lokpal ensure judicial accountability?

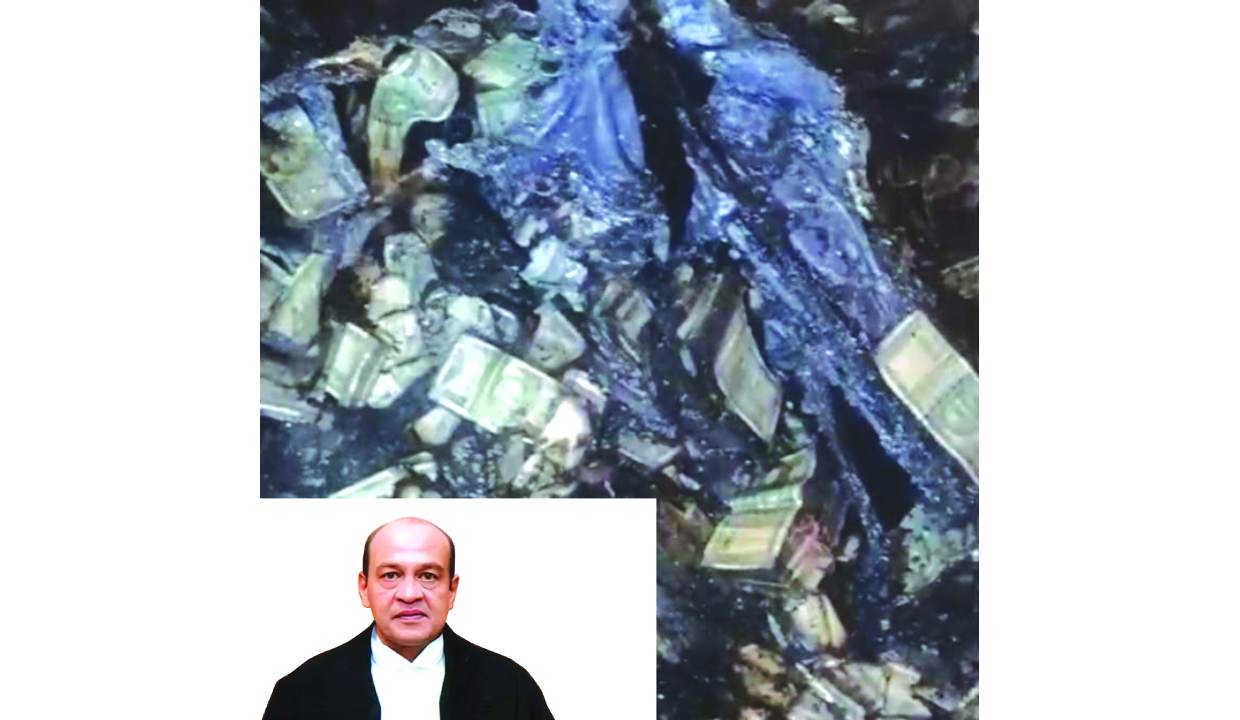

Impeachment proceedings have been initiated against Justice Yashwant Varma in connection with the Cash-at-Home case. The process was officially triggered in July 2025 following the discovery of unaccounted cash at Justice Varma’s official residence in New Delhi, where burnt wads of currency notes were found in a storeroom after a fire incident on March 14, 2025.

Justice Varma has since been transferred from the Delhi High Court to the Allahabad High Court and has been assigned to non-judicial work. Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla admitted the motion of impeachment on July 21, 2025, and subsequently constituted a three-member investigation committee on August 12, 2025.

While Parliament moved forward, Justice Varma challenged the process in the Supreme Court. On December 16, 2025, the Supreme Court flagged a potential violation of the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968.

Justice Varma argues that because motions were submitted in both Houses on the same day, the committee should have been formed jointly by the Speaker and the Rajya Sabha Chairman. Instead, the Speaker acted “unilaterally.”

The Supreme Court expressed surprise that with so many legal experts in Parliament, this procedural requirement was overlooked. The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear the matter next on January 7, 2026, to decide if the current impeachment process is legally valid or if it must be restarted according to the strict letter of the law. The case of Justice Varma serves as a current example of how difficult the impeachment process is in India. Because the procedure is so rigorous and requires a special majority, no judge has ever reached the final stage of removal by the President. The primary legal basis for the removal of a judge is found in Article 124(4) of the Constitution for Supreme Court judges and Article 217 (read with Article 124(4)) for High Court judges.

Since there has been no successful removal of judges on grounds of proved misbehaviour like corruption or bribery, financial Irregularities, moral turpitude, abuse of power, the question arises whether there is a necessity to evolve a fresh procedure.

A glimpse of it was manifested on January 14, 2025, when the Lokpal decided that it possessed the jurisdiction to entertain and investigate corruption complaints against sitting High Court judges, a decision that was subsequently stayed by the Supreme Court on February 20, 2025.

The full bench of Lokpal passed the order asserting that High Court judges fall under the definition of “public servants” in the Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013. The Supreme Court took a suomotu cognisance of the Lokpal order and, after orally observing that it was “procedurally disturbing,” decided to examine the entire issue by taking assistance of senior advocates — Kapil Sibal and Shri BH Marla Palle. The three-judge Bench described “the matter is of great significance concerning the independence of the judiciary.” The Case Status of the Supreme Court website reflected as pending the matter in which the Union of India is one of the respondents. It would be interesting to note the stand of the two senior counsel, acting as amicus curiae, particularly Sibal, who has represented Justice Varma in the “cash-at-home” controversy and has taken a very aggressive stance against both the judiciary’s in-house inquiry and the Government’s role in the matter.

While the removal of a judge through an impeachment motion in Parliament has long been a subject of debate, the Lokpal’s decision — now under the judicial lens of the Supreme Court — has ignited a fresh controversy. Some observers are raising a critical question: when the constitutional process of impeachment proves politically unworkable or cumbersome, should credible prosecution through institutions like the Lokpal be allowed to proceed without obstruction?

However, this suggestion has not been well-received by several legal experts, including Senior Advocates Siddharth Luthra and Vikas Pahwa. They contend that involving the Lokpal is not the way forward, arguing that such ‘populist shortcuts’ would be far more damaging to the rule of law than the problem they seek to address. While expressing disagreement with the Lokpal’s January 14, 2025, order

asserting jurisdiction over corruption complaints against sitting High Court judges, both Senior Advocates maintain that the prevailing constitutional scheme ensures judicial independence and functionality and that these core values cannot be sacrificed at the altar of public outrage or ‘institutional adventurism’.

“I totally disagree with the suggestion that because judicial impeachment is politically difficult, institutions like the Lokpal should be allowed to step in and prosecute judges without restraint,” said Pahwa. He said impeachment of a Judge is intentionally made difficult. “It is a constitutional safeguard, not a procedural failure.

The framers of the Constitution consciously placed the removal of judges behind a high political threshold to ensure that judicial independence is not sacrificed at the altar of public outrage or institutional adventurism,” the Senior advocate said. Pahwa said the Lokpal, though a statutory authority, is neither constitutionally superior nor insulated from political influence and “to project it as a neutral substitute for impeachment is fundamentally flawed.”

Allowing a statutory body to assume authority over constitutional judges simply because impeachment is “unworkable” would amount to short-circuiting the Constitution itself, he said. Taking forward, Luthra said the judiciary is the third limb of the Government, judges are constitutionally protected, bodies like the Lokpal can’t really be used to sit over judgment of what they do. “There is a reason why the provisions in Article 124 (4) and 217 were kept because the idea is to sustain the independence of the judiciary and its functionality,” he said. “To my mind, handing over the reins of a supervisory role to the Lokpal, headed by a retired Supreme Court judge, is not the way forward,” the Senior Advocate said. While posing the question, could there be any independent regulator and answering in the affirmative, Luthra said, alternatively, to achieve a relevant and competent independent regulatory body to look into various aspects of the functioning of judges, the Government should consider giving legal legitimacy and constitutional legitimacy to the in-house procedure that exists by amending Article 124 and providing Constitutional sanctity to it.

“I think that will be a fine balance for the in-house procedure, which really operates on the basis of an interpretational exercise of the Supreme Court, becomes a legitimate exercise under the Constitution,” he said.

Making it clear that Judicial accountability cannot be enforced by bypassing constitutional processes, Pahwa said, “if statutory bodies are permitted to investigate or direct prosecution against judges without impeachment or constitutionally recognised in-house procedures, it would open the floodgates to motivated complaints, pressure tactics, and erosion of judicial independence.”

“The solution to corruption in the judiciary does not lie in weakening constitutional protections, but in strengthening internal accountability while preserving institutional autonomy. Any other approach risks replacing constitutional governance with populist shortcuts, and that would be far more damaging to the rule of law than the problem it seeks to address,” Pahwa concluded.