Dalal Street dalliance, IPO alliances, FPI defiance, and retail dominance

In the not-so-distant time, when the SpaceX rockets and satellites dominate outer space, and the firm goes public, it may be valued at $1.5 trillion, shooting up the net worth of its founder, Elon Musk, to $1 trillion, or more. Although we can peep light years behind to gaze, explore, and understand the faraway stars, galaxies, and black holes, such numbers can still boggle the minds. Musk is now worth

nearly $750 billion, as per Forbes real-time list of billionaires, and it is not unusual for his wealth to change by $100 billion a day.

Billionaires’ wealth is indeed going through the sky. Like the universe it seems unending, although experts tell us that there may indeed be an end somewhere out there. According to Forbes 2025 list, there were more than 3,000 billionaires with a total wealth of more than $16 trillion. But the list came out earlier in the year, when Musk was worth less than half of what he is today. So, the final figure may be nearer to $20 trillion. As we said before, the numbers do not make sense; and we understand the black holes better.

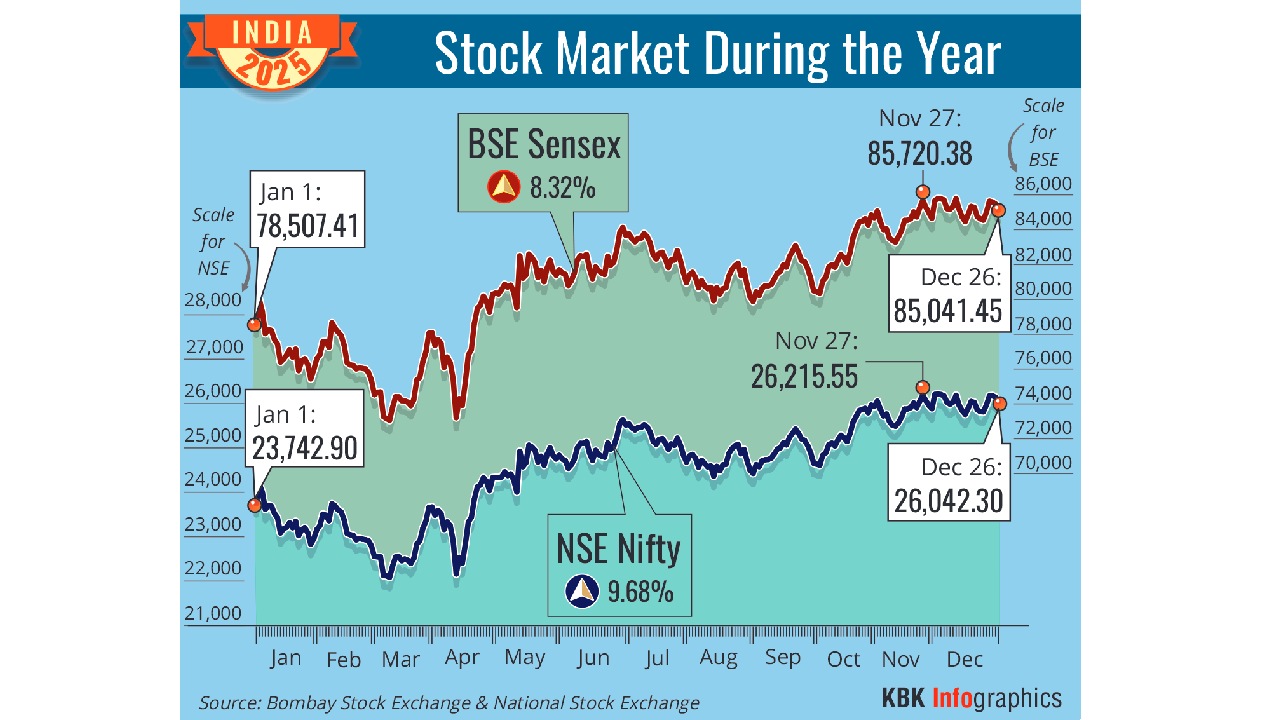

However, the fate of the Indian billionaires was not too good this year. This was largely because the Sensex was up just over eight per cent, and added just over 6,500 points. However, most of the returns came in the past three months, especially after GST 2.0. Until September 2025, the index was almost flat with near-zero returns. The top 100 billionaires (Forbes’ real-time list as on December 28) featured six Indians, if one includes Lakshmi Mittal ($23.5 billion; Rank 98), who is based in London but may shift elsewhere.

The top spot for an Indian went to Mukesh Ambani’s (more than $110 billion; Rank 16)), followed by Gautam Adani ($66 billion; Rank 27), Savitri Jindal ($36 billion+; Rank 58), Shiv Nadar ($36 billion; Rank 59), and Dilip Shanghvi ($25.5 billion; Rank 92). Although we maintain that these valuations, being based on paper or the stocks owned by the founder-promoters, are meaningless, one cannot say the same about the stock markets. They are a valuable and powerful source of funds, and an important marker of the economy.

When the Sensex was launched as an index in 1986, I was a rookie journalist, and it stood at 570 points. In 1990, it crossed 1,000, and now it is more than 85,000 despite the various scandals that mocked it on the near four-decade roller-coaster journey. In effect, the returns from the index since its inception is close to 16,000 per cent, another meaningless figure since the stocks that comprise the index have changed, with many dead or disabled on the way. What is more important is that the annualised returns from the index strikingly resemble the annual nominal rate of GDP growth.

Yet, this year was one of deviation, defiance, dominance, alliances, and dalliances. If we consider the first half of this fiscal year, for which the growth figures are available, the Sensex moved up by just over five per cent, which is lower than the nominal growth. The foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) defied the trends in most of the other emerging markets, and withdrew a record INR 1,00,000 crore. It was mostly the local retail investors, who dominated the stock show with their dalliances and alliances, and helped the index to be stable.

Despite being the fastest-growing economy among the major ones, the FPIs walked out. But their relevance is vastly reduced, and they account for barely 17 per cent of the stock market valuations. Indian investors stepped in as the main actors, and the assets under management of the mutual funds, the go-to choice for the retail investors, shot up to over INR 80 trillion by end-November 2025. In addition, stock investment has moved from the minority to the middle class across the metros, and Tier I, II, and III cities.

Let us look at the demat accounts. As of 2025, there are about 200 million-plus accounts, and more than 50 per cent may be active ones. Even if one discounts multiple accounts, 80-90 million people may invest in stocks. They represent the middle and upper-middle class. Although other asset classes like gold, silver, and real estate delivered decent returns, especially in the past few years, Indians have moved from savings to investments. Still, most are cautious and risk-averse. In several surveys, safety and security of the money comes first, and a majority is willing to earn lower returns for it.

Such optimism, and contradictions are reflected in IPOs (Initial Public Offerings), which boomed in 2025. There were more than 100 IPOs, and towards the end, retail investors joined the queue to rake in listing gains, or the difference between the offer prices of the stocks, and prices on the respective listing days. In some cases, the listing gains were massive, up to 50 per cent. In others, they were meagre. In many cases, stock prices dropped below the offer and listing prices within months. The bad apples came with the good ones such as Tata Capital, Groww, LG Electronics, and Meesho.

Although the retail investors withdrew from the secondary market towards the end of 2025, they did not mindlessly rush into IPOs. In many cases, despite high grey market premiums, or pre-IPO indications of listing gains, the retail portions were not fully subscribed, or subscribed at lower levels compared to the institutional portions. The small investors remained careful, although many did not do due diligence, and based decisions on hearsay. What is crucial is that even the FPIs, who sold stocks in the secondary market, flocked to invest in several IPOs.