A budget built for big dreams

In her ninth consecutive budget, which includes an interim one, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman combined a grand futuristic vision with micro-technical tinkering, partly shied away from big-ticket reforms and immediate radical changes, and did not focus too much on the financial numbers that seemed weak and unstable.

She started the speech with a few bangs and ended up in a whimper. Analysts and experts ran around to understand the technical nitty-gritties of the budget, frustrated investors pulled the Sensex down by more than 1,800 points, and the middle class licked their fingers in disappointment. The industry hid its lack of enthusiasm behind the proposals that hinted at changes over the next 5, 10, and 20 years.

The vision came in the form of several proposals that indicated the Government’s commitment over the next several years. For example, Sitharaman proposed a high-powered standing committee on ‘education-to-employment and enterprise,’ which would prioritise areas for growth, employment, and exports in the services sector, and assess the impact of emerging technologies, including AI, on jobs and skills. The recommendations would possibly make India a global leader in services, “with a 10 per cent global share by 2047.”

Similarly, a Coastal Cargo Promotion Scheme aims to incentivise a shift from rail and roads, “to increase the share of inland waterways and coastal shipping from six per cent to 12 per cent by 2047.” Inland waterways re-emerged as a theme, and the finance minister proposed 20 new National Waterways over the next five years. Indeed, the five-year theme was a recurrent one for several proposed projects. In the case of healthcare, there was a proposal, Bio-pharma Shakti, to build the ecosystem for local production of biologics and bio-similars, apart from a network of 1,000 accredited Indian Clinical Trials sites. The outlay was INR 10,000 crore over the next five years.

Sitharaman said that the country would upgrade existing institutions and build new ones for allied healthcare professionals. These agencies were likely to cover 10 selected disciplines, and “add 1,00,000 AHPs (professionals) over the next five years.”

There was an outlay of INR 20,000 crore, in alignment with the Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage roadmap launched in December 2025, to achieve “higher readiness levels in end-use applications across five industrial sectors.” But the amount would be spent, if it was allocated, over the next five years. Cities, according to the finance minister, were “engines of growth, innovation, and opportunities,” and it was time to change the focus to the smaller cities and towns. Hence, the Budget aimed to map city economic regions (CER), and proposed an allocation of INR 500 crore per CER, or city, “over five years” to implement their plans.

Part B of the speech, which deals with taxes and duties, was completely technical and micro-oriented, with dozens of tax tinkering. Although many of them were crucial, and necessary, they failed to enthuse the public. No tax on interest awarded by the court in motor accidents, lower tax collected at source on overseas tour packages, tax deducted at source of 1-2 per cent on contractors for supply of manpower to them, or zero tax on payments due to compulsory acquisition of land by the Government under the law. Apart from the more than 20-year tax holiday, until 2047, “to any foreign company that provides cloud services to customers globally by using data centre services from India,” and a one-time 6-month foreign asset disclosure scheme for small taxpayers like students, young professionals, and techies, most of the tax proposals were full of legal and technical jargon.

There were no big breaks for the middle class, apart from the clarification on buybacks of shares by firms. Instead, this class was saddled with more taxes, on investing in futures and options, zero tax break on sovereign bonds unless they were purchased initially, and the buyers held on to them till the maturity date.

Part B was full of process simplification, especially on the customs side, which is crucial, but lacked specifics, apart from a few segments. Before the Budget speech, analysts felt that Part B would be longer than Part A, and signal dramatic rationalisation in the form of zero duties on raw materials, higher ones on components and intermediates, and the highest on finished products. It was not to be.

Many experts had predicted, or hoped, that this was the best year for Sitharaman to unveil a practical and workable vision, both short-term and medium-term, to guide the economy onto a new, rejuvenated journey. There were grand announcements for the future, 5, 10, and 20 years, but the path seemed foggy and partly visible.

One of the reasons was probably because the finance minister was caught in a bind over the financial numbers related to revenues and expenditure. This may explain why Sitharaman rushed through the numbers in Part A of the speech, and mainly focused on official debt and fiscal deficit, which were clearly the big positives.

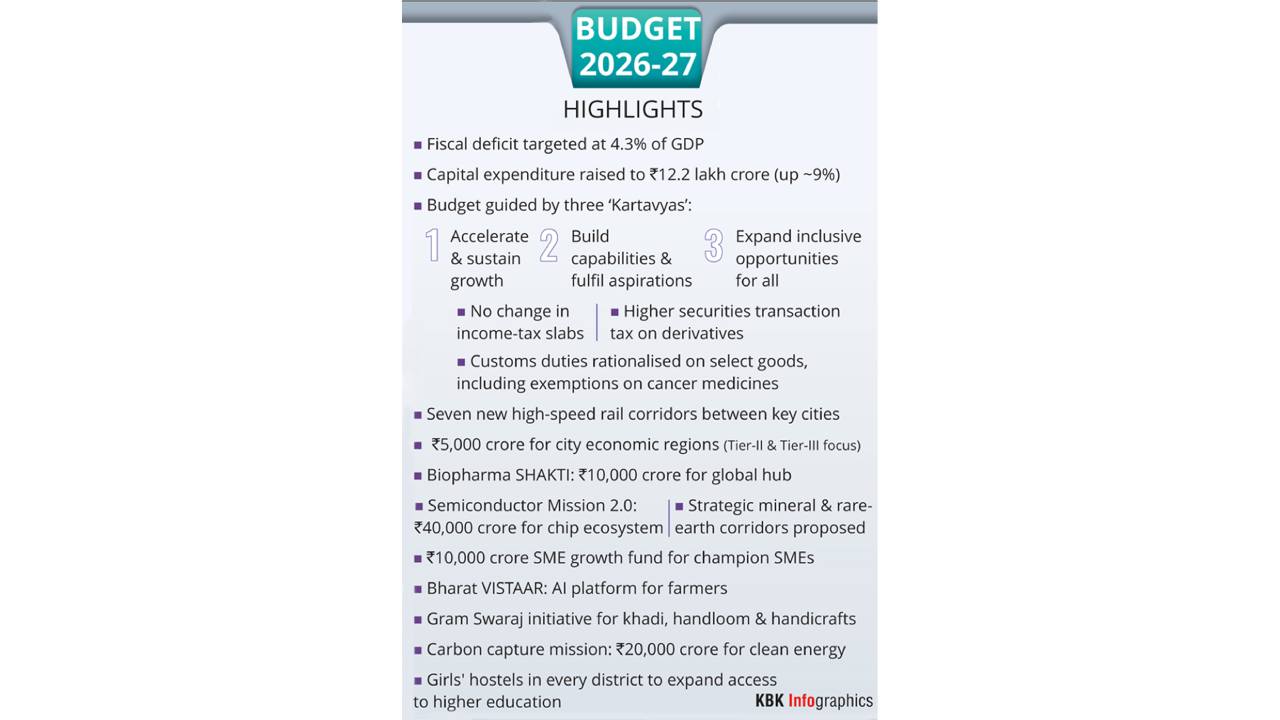

It is true that the finance minister, as she proudly claimed, managed to bring down the deficit figure to what she promised during the pandemic, when the figure zoomed to a seemingly unmanageable percentage. In 2025-26, the revised estimate for the fiscal deficit is 4.4 per cent of the GDP, or below 4.5 per cent as she had promised, with the budgeted figure for 2026-27 at 4.3 per cent.

However, in taking credit, Sitharaman hid more than she revealed. As per the revised revenue estimates for 2025-26, the figure is nearly Rs 80,000 crore lower than the previous budget estimates made at the beginning of the year during last year’s Budget. The tax revenues, net to the Centre, may be more than INR 1,50,000 crore lower when this fiscal year ends on March 31. This implies that the Government’s estimates that it will lose INR 50,000 crore on account of GST 2.0 due to lower tax slabs were haywire. Even the capital receipts may be lower than budgeted estimates.

When it came to GST, the revised gross estimates for the year may be lower by more than INR 1,30,000 crore. A further negative may be in the form of income taxes, and the revised estimates are lower than the budgeted estimates. Only corporate tax, or tax paid by firms, showed buoyancy, and will be marginally higher than the earlier estimates. In total, the revised estimates for gross tax revenues may be nearly INR 2,00,000 crore lower once the fiscal year ends.

Hence, to bring the fiscal deficit under control, and maintain it at 4.4 per cent, as projected in the last budget, the Government will spend less this fiscal, and reduce its market borrowings. The revised estimate for total expenditure in 2025-26 is INR 35,000 crore or so lower than the earlier budget estimates.

A slash in revenue expenditure, estimated at INR 75,000 crore, may prove to be a saviour by the end of the year. In her speech, Sitharaman confidently said, “Public capex (capital expenditure) has increased manifold from INR 2 lakh crore in 2014-15 to an allocation of INR 11.2 lakh crore in 2025-26 (original budget estimates). I propose to increase it to INR 12.2 lakh crore to continue the momentum.”

What the finance minister failed to mention was that the revised estimate for public capex was down to INR 10.96 lakh crore in 2025-26, or lower than the budgeted estimate she mentioned. The revised effective expenditure on capital account, which included capital account and grants-in-aid to create capital assets, was down by nearly INR 1,50,000 crore. To manage the fiscal deficit, the Government lowered its market borrowings and other liabilities by around INR 1,10,000 crore.