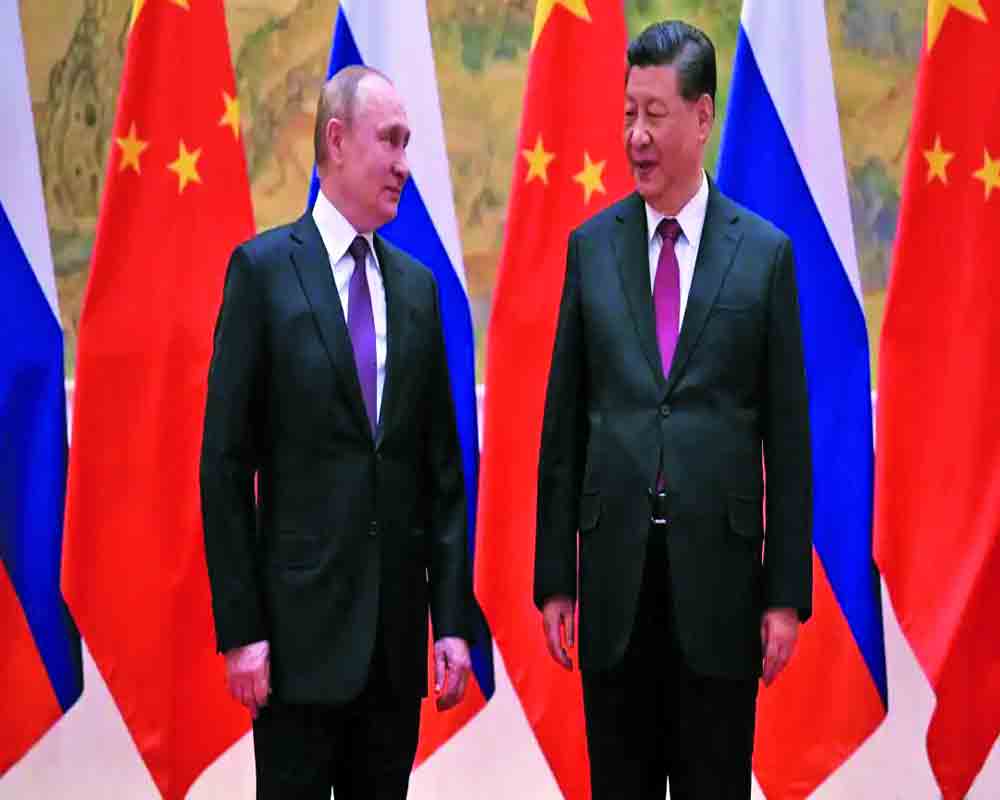

China and Russia are working with Pakistan and Iran to squeeze strategic space of the Unites States in West Asia

In the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides stated that "the surest way of harming an enemy is to find out certainly what form of attack he is most frightened of and then to employ it against him". The insecurity of the US has easily led it to fall into the trap of its competing powers. Russia and China have worked together jointly to isolate the US by creating circumstances in which Washington either adopts a very harsh approach or quits the region altogether. Iran and Afghanistan are two such cases.

The relations between Iran and Russia had remained very minimal given the loss of Iranian territories in the South Caucasus via the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828). Russia and Iran are the heirs to great empires; they have inherited the same zeal to reclaim their rightful places. It was this instinct to bring back their respective past glory that accelerated the process of their coalition.

As part of their geopolitical strategy, Russia and China always portrayed that they were willing to support the US, but simultaneously worked jointly to cut short the American influence. For instance, Russia concluded a secret deal in 1995, the Gore-Chernomyrdin agreement, in which Moscow agreed to end the supply of its conventional weapons to Iran by 1999. Second, from June 2006 to June 2010, Russia and China did not use their veto in the UNSC to stop sanctions against Iran. This was the same period wherein the US was involved in its war on terror in Afghanistan.

Statistically, during the period described above, Russia and China increased their strategic outreach in Iran. Arms trade between Iran and Russia ballooned from $300 million between 1998 and 2001 to $1.7 billion between 2002 and 2005, and more than 70 per cent of Iran's arms imports came from Russia. In 2016, the delivery of S-300 was completed, and China emerged as Iran's second largest arms supplier. From 2010 onwards, Russia and China used their veto to favour Iran.

Russia has always stressed an international system which cannot be headed by any single power. It adopted its multi-vectored foreign policy, and Iran, on the other hand, went ahead with its 'Look East' policy with a primary focus on Russia, China and India. Further, the emergence of polyarchic actors and their respective interests imposed limits on the use of coercive diplomacy. Grounds for further cooperation thus emerged. A joint anti-American stand having four dimensions brought the two strategically closer. First, opposition to the NATO expansion; Second, American support for the velvet revolutions in the strategic backyards of Russia and Iran-Ukraine, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan; Third, their shared understandings of the causes of Sunni radicalism in South and West Asia, and finally, their joint support to Syria's Assad regime.

As the new Cold War gradually progressed, Putin withdrew from several agreements with the US, such as the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, Open Skies treaty, etc. When Putin visited Iran in 2017, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei stated that the Russo-Iran cooperation could potentially isolate the US. The current hardliner Ebrahim Raisi firmly believes that Tehran is facing an 'existential threat' and should side with the other similar oppressed powers like Russia and China by forming an "axis of resistance".

Currently, the nuclear deal is something that everyone is keenly watching. Biden has been hesitant to give vital concessions to Iran in lieu of the revival of the nuclear treaty. If the deal is not revived, it will usher in more instability in the West Asian region and beyond. The West might lose its battle of nonproliferation in West Asia. If Iran goes nuclear, Russia and Iran will increase their asymmetric warfare in the region. Perhaps it may take just a few months for Israel and Iran to get militarily involved and increase the risk of an armed conflict in West Asia, which will have consequences for the Abraham Accords. The success of the Biden administration would be to ensure that the accords remain functional and Iran is kept engaged. From that perspective, the revival of the deal is essential.

On the other hand, if seen from an Israeli perspective, the revival of the deal might not be in its interests, and Israel might perceive it as a geopolitical 'compromise' with the nuclear blackmailing tactics of Iran. It would raise the bargaining power and geopolitical importance of Iran. Israel might see it as a shift in the American focus to prove its credibility to its other allies owing to the Chinese threat to Taiwan, India and Japan. It might strain the American and Israeli ties. For the US, the choices as of now remain limited. It cannot risk a conflict in West and East Asia simultaneously.

Washington's uncertainty over the deal can somewhat be compared to the same dilemma of the US when questions arose over its withdrawal from Afghanistan. Today, Russia and China have created the same labyrinth for the US as they did in Afghanistan. Russia and China aided by Pakistan, got the tripartite talks on Afghanistan converted into the six-party talks, thereby diplomatically entangling the US. Simultaneously, reports of Russia rearming the Taliban were in the news, which the US could not do much about it. On the other hand, Pakistan extracted military and financial gains apart from aiding the Taliban. Consequently, the US had adopted a soft approach to terrorist groups such as the Lashkar–e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish–e- Mohammad (JeM). China, on its part, initiated its OBOR and announced physical outreach to South and Central Asia, thereby making the US feel insecure and provoking Washington to continue its military presence in Afghanistan. The American presence in Kabul provided a much-required security cushion to Chinese regional investments. Also, Beijing normalized its relations with Afghanistan in 2016 and extended aid worth $73 million to Kabul. It also proposed to set up an anti-terror alliance at a regional level with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, thereby indicating its future military involvement in Central Asia. Thus, the US was lured strategically to continue its presence.

For long, the US was in the classic Shakespearean dilemma of "to be or not to be", which had consequences. In 2015-16, Admiral Bob Inman, a US security expert understood the Sino-Russo game plan and called for the Americans to exit Afghanistan through a cooperative security arrangement with SCO, but given the questions on the "strategic ego", the recommendation was sidelined. As the situation deteriorated rapidly, Washington hurriedly started negotiations with the Taliban, and by 2021 it had to evacuate, leaving behind its "treasure" of military equipment that possibly would have been reverse engineered by China by now.

If one observes post-US exit, the amount of Chinese aid and investments has decreased drastically, and it is hesitant to invest in an insecure environment. China is extracting the natural resources of Afghanistan in lieu of its trade. The same would be done for Iran. As the US prepares to drop out from the revival of the treaty on the grounds of not being "constructive", the emergence of the new Quad between Russia, China, Pakistan and Iran is almost imminent. It would usher in instability for South and West Asia. In the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides stated that "the surest way of harming an enemy is to find out certainly what form of attack he is most frightened of and then to employ it against him". The insecurity of the US has easily led it to fall into the trap of its competing powers. Russia and China have worked together jointly to isolate the US by creating circumstances in which Washington either adopts a very harsh approach or quits the region altogether. Iran and Afghanistan are two such cases.

The relations between Iran and Russia had remained very minimal given the loss of Iranian territories in the South Caucasus via the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828). Russia and Iran are the heirs to great empires; they have inherited the same zeal to reclaim their rightful places. It was this instinct to bring back their respective past glory that accelerated the process of their coalition.

As part of their geopolitical strategy, Russia and China always portrayed that they were willing to support the US, but simultaneously worked jointly to cut short the American influence. For instance, Russia concluded a secret deal in 1995, the Gore-Chernomyrdin agreement, in which Moscow agreed to end the supply of its conventional weapons to Iran by 1999. Second, from June 2006 to June 2010, Russia and China did not use their veto in the UNSC to stop sanctions against Iran. This was the same period wherein the US was involved in its war on terror in Afghanistan.

Statistically, during the period described above, Russia and China increased their strategic outreach in Iran. Arms trade between Iran and Russia ballooned from $300 million between 1998 and 2001 to $1.7 billion between 2002 and 2005, and more than 70 per cent of Iran's arms imports came from Russia. In 2016, the delivery of S-300 was completed, and China emerged as Iran's second largest arms supplier. From 2010 onwards, Russia and China used their veto to favour Iran.

Russia has always stressed an international system which cannot be headed by any single power. It adopted its multi-vectored foreign policy, and Iran, on the other hand, went ahead with its 'Look East' policy with a primary focus on Russia, China and India. Further, the emergence of polyarchic actors and their respective interests imposed limits on the use of coercive diplomacy. Grounds for further cooperation thus emerged. A joint anti-American stand having four dimensions brought the two strategically closer. First, opposition to the NATO expansion; Second, American support for the velvet revolutions in the strategic backyards of Russia and Iran-Ukraine, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan; Third, their shared understandings of the causes of Sunni radicalism in South and West Asia, and finally, their joint support to Syria's Assad regime.

As the new Cold War gradually progressed, Putin withdrew from several agreements with the US, such as the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, Open Skies treaty, etc. When Putin visited Iran in 2017, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei stated that the Russo-Iran cooperation could potentially isolate the US. The current hardliner Ebrahim Raisi firmly believes that Tehran is facing an 'existential threat' and should side with the other similar oppressed powers like Russia and China by forming an "axis of resistance".

Currently, the nuclear deal is something that everyone is keenly watching. Biden has been hesitant to give vital concessions to Iran in lieu of the revival of the nuclear treaty. If the deal is not revived, it will usher in more instability in the West Asian region and beyond. The West might lose its battle of nonproliferation in West Asia. If Iran goes nuclear, Russia and Iran will increase their asymmetric warfare in the region. Perhaps it may take just a few months for Israel and Iran to get militarily involved and increase the risk of an armed conflict in West Asia, which will have consequences for the Abraham Accords. The success of the Biden administration would be to ensure that the accords remain functional and Iran is kept engaged. From that perspective, the revival of the deal is essential.

On the other hand, if seen from an Israeli perspective, the revival of the deal might not be in its interests, and Israel might perceive it as a geopolitical 'compromise' with the nuclear blackmailing tactics of Iran. It would raise the bargaining power and geopolitical importance of Iran. Israel might see it as a shift in the American focus to prove its credibility to its other allies owing to the Chinese threat to Taiwan, India and Japan. It might strain the American and Israeli ties. For the US, the choices as of now remain limited. It cannot risk a conflict in West and East Asia simultaneously.

Washington's uncertainty over the deal can somewhat be compared to the same dilemma of the US when questions arose over its withdrawal from Afghanistan. Today, Russia and China have created the same labyrinth for the US as they did in Afghanistan. Russia and China aided by Pakistan, got the tripartite talks on Afghanistan converted into the six-party talks, thereby diplomatically entangling the US. Simultaneously, reports of Russia rearming the Taliban were in the news, which the US could not do much about it. On the other hand, Pakistan extracted military and financial gains apart from aiding the Taliban. Consequently, the US had adopted a soft approach to terrorist groups such as the Lashkar–e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish–e- Mohammad (JeM). China, on its part, initiated its OBOR and announced physical outreach to South and Central Asia, thereby making the US feel insecure and provoking Washington to continue its military presence in Afghanistan. The American presence in Kabul provided a much-required security cushion to Chinese regional investments. Also, Beijing normalized its relations with Afghanistan in 2016 and extended aid worth $73 million to Kabul. It also proposed to set up an anti-terror alliance at a regional level with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, thereby indicating its future military involvement in Central Asia. Thus, the US was lured strategically to continue its presence.

For long, the US was in the classic Shakespearean dilemma of "to be or not to be", which had consequences. In 2015-16, Admiral Bob Inman, a US security expert understood the Sino-Russo game plan and called for the Americans to exit Afghanistan through a cooperative security arrangement with SCO, but given the questions on the "strategic ego", the recommendation was sidelined. As the situation deteriorated rapidly, Washington hurriedly started negotiations with the Taliban, and by 2021 it had to evacuate, leaving behind its "treasure" of military equipment that possibly would have been reverse engineered by China by now.

If one observes post-US exit, the amount of Chinese aid and investments has decreased drastically, and it is hesitant to invest in an insecure environment. China is extracting the natural resources of Afghanistan in lieu of its trade. The same would be done for Iran. As the US prepares to drop out from the revival of the treaty on the grounds of not being "constructive", the emergence of the new Quad between Russia, China, Pakistan and Iran is almost imminent. It would usher in instability for South and West Asia.

(The author is Assistant Professor, Central University of Punjab)