In the coming years, Asian relations might be marked by increasing hostility and shifting sands of strategic alignments

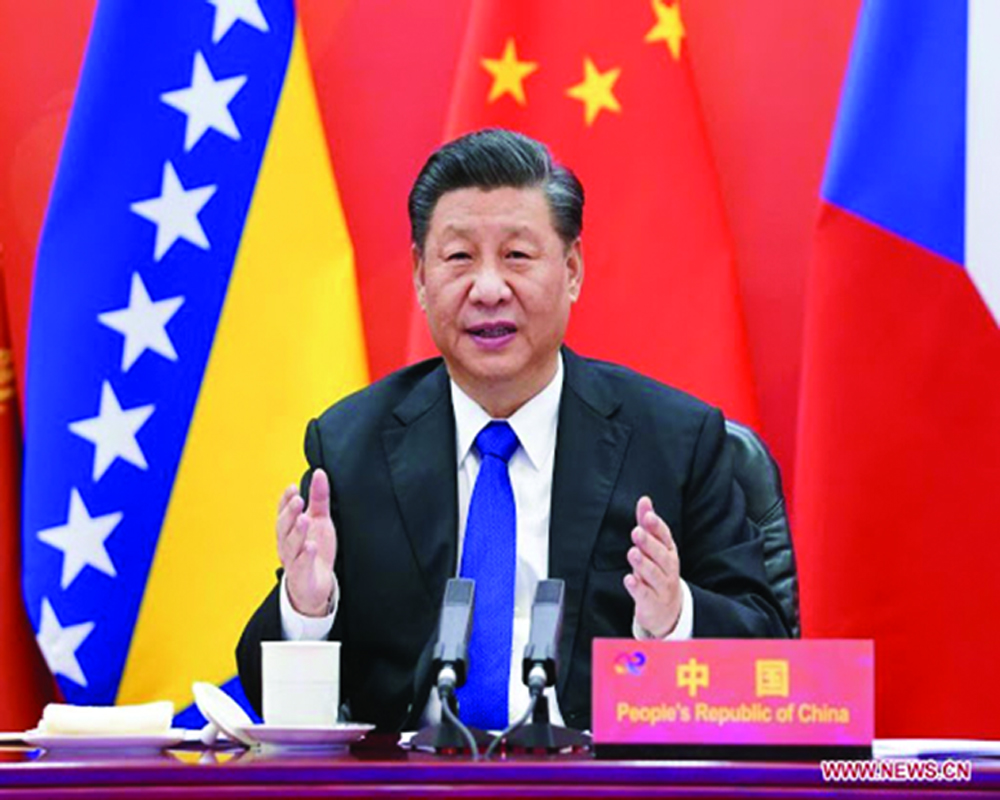

Beijing’s wolf warrior diplomacy through its aggressive posturing is already well established. A question that baffles many is how President Xi Jinping has taken over the Chinese society and economy to strengthen his reign — something that his predecessors couldnot think of.

One has to accept that when Xi took over in 2013, the economy was much better than it was previously when Hu Jintao had taken over. Also, because of Hu’s initiatives, intellectuals had the freedom to express their concerns on serious issues, which they lost when Xi assumed power. Immediate domestic issues that he faced were employment generation, accommodating the excess manufacturing output, environmental degradation, and food security. The rise of the middle class added to his woes. At the international level, initiatives such as ‘March West’, the OBOR, and ‘circular lending’ through its debt trap policies were efforts to find solutions. As this is a time-consuming job, it became pertinent for Xi to control the raising dissent voices and from there his journey of throttling the society began.

As a first response, in 2013, at the 18th Party Central Committee’s Third Plenum, Xi introduced “social management” to bring about “law and order” to ensure “stability”. This led to the establishment of a National Security Commission, and later in 2014, Social Credit System (SCS) which worked hand in glove with one another. The objectives of these institutionalised governance mechanisms were to monitor individual behaviours to ascertain their loyalty to the regime and party cause so that a “rule of law” could be established. Whipping followed the structural framework. For instance, in 2015, Xi Jinping made it mandatory for all the NGOs in the country to have CCP party cells that would work in coordination with the PSB that paved the way for CCP’s anti-corruption drives. Many liberal NGOs were either shut down or taken over by the party cadres. In the same year, Party sacked the editor of the Xinjiang Daily, Zhao Xinwei, for his “inappropriate” discussions on the policies of the government. Several others such as the Chongqing party chief, Bo Xilai, and former Politburo Standing Committee member, Zhou Yongkang, were not spared and removed from their positions so that Xi could get a clear path.

Second, Xi transformed ‘United Front’ to ‘Great United Front’ and targeted to broaden the range of party influence in various sectors of the society. Aiming for social control, in 2015, CCP convened its first conference, and ever since then it is unstoppable. Under this initiative, Xi has attempted to reach out to the “non- Party intellectuals” who comprise students, media professionals, and businesses of Chinese origin. It aimed to ‘develop friendship’ through “pairing up” by establishing linkages between CCP workers and “non-Party intellectuals” through a patron-client relationship, which the experts call a “clientelistic state corporatism”. This was supplemented with an introduction of a new model of social governance in 2017 that emphasized “collaboration, participation, and common interests” in which it was affirmed that the “Party committees exercise leadership, the government assumes responsibility”.

In 2018, Xi abolished the term limits to his presidency consequently to which he now stands virtually as a permanent President. To attain the safety and security of his reign he further placed the People’s Liberation Army reserve forces under his direct control and the Central Military Commission, a move that slashed the powers of the PLA and the local governments. The functioning of this structure allows the CCP to place their representatives in almost all business houses and also open up their financial balance sheets and other important databases for scrutiny by the CCP officials at any time. Students, especially the research scholars studying abroad have been tasked to bring in information so that it can be of help to China.

Third, the use of Chinese Intelligence Services (CIS) towards the ‘thousand grains of sand’ theory to link the cause of Xi to the citizens by making it inescapable for them to work for the cause of state objectives complicates the situation still further. Working in the framework of “multiple professional systems” seems to be an inexpensive method of getting cooperation and loyalty from the people. The 2017 National Intelligence Law obligated the citizens, companies, and organisation under Articles 7 and 14 to undeniably support the state intelligence agencies. Further, the law also gives sweeping powers to the intelligence agencies to “investigate” foreign companies, organisations, and individuals on its soil. Such laws combine the civil and physical defence to punish any dissenting voices and are unheard of in democratic countries.

Fourth, the closure of certain think tanks organisations such as the Unirule Institute of Economics that promoted political liberalization also speaks volumes of tighter controls. Nevertheless, media censorship has also played an important part in Xi’s consolidation of power. The Cybersecurity Law that was introduced in 2016 directed the service providers that the data of its citizens shouldn’t be stored outside China. Also, the banning of the Signal end-to-end encryption messaging app and the systemic pressures to shut down Apple Daily that used to provide neutral access to the foreign and security policy raises concerns of tighter academic and intellectual controls under Xi. With various social media such as Twitter, Youtube and Facebook already banned, the social unrest of the young Chinese might feel claustrophobic which is not good for Beijing. The integration of the “Great Firewall” and “Great Cannon”—responsible for the inflow and the outflow of information through the internet and propaganda warfare respectively — is also an area of concern for the world. The death of Li Wenliang, the Chinese whistle-blower of the Corona epidemic, is yet another example ofthe alarming conditions.

Fifth, even the judicial systems have not been spared. In 2020, the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission which is responsible for overlooking China’s police and law enforcement agencies came under the ambit of the “education and rectification” campaign to “remove tumors” or the “two-faced men”. Such programs encourage mandatory self-reporting and ideological indoctrination to confirm that only those loyal to the leader and its style of functioning remain within the system thus resulting in a major shuffling of its staff. Supposed to be lasting till 2022, one can easily comprehend the role of such an initiative in the upcoming 20th Party Congress scheduled next year.

Finally, one can confidently put across the view that it wouldn't be a major surprise next year if Xi Jinping continues to be in command of Chinese affairs. This will have repercussions throughout the world. It appears that the world is already gearing up for this as it seems to understand the domestic functioning of China. In the coming years, Asian relations might be marked by increasing hostility and shifting sands of strategic alignments that might force democratic countries like India to bring profound changes in their military and operational doctrines. At a domestic level, as China’s espionage infiltration increases it might mandate other democratic states to enhance their counter-espionage methods as well as regulations.

(The writer is an Assistant Professor at Central University of Punjab, Bathinda. The views expressed are personal.)