What is popular culture? Is it a real manifestation of the expressions of the working and lower-middle classes or is it imposed from above? And can States control it?

Recently a short video made by Dananeer Mobeen, a young Pakistani woman, went viral in the subcontinent and spawned a host of memes. It was a casual video in which the woman lightheartedly parodied the Americanised Urdu accents of certain upper-class Pakistanis. Indeed, viral videos and memes are nothing out of the ordinary. Their “fame” usually lasts a few days. Like most popular culture products, they are quickly consumed and then disposed. But like any other popular culture product they, too, can add something substantial to an ongoing social or political discourse. Popular culture products have rapidly evolved, but their nature has remained the same. They have managed to not only exercise social influence but also impact various political aspects of a society. It is thus not uncommon for governments to ban or try to control certain products of popular culture.

But what is popular culture? Is it a recent occurrence or was there always a popular culture when humans began to band together as societies? Professor of Cultural Studies John Storey writes in his book, ‘Inventing Popular Culture’, that the term “popular culture” was first coined in 19th century England. According to Storey, popular culture was a product of industrialisation and the consequential urbanisation in Europe, when cities began to grow and witnessed an influx of migrants from rural areas arriving to work in factories. They brought with them, what came to be known as, folk culture. But in a rapidly evolving urban modernity, folk culture was derided as being superstitious, conservative and static.

In response, the urban working classes with roots in the rural areas formulated their own modernity, by utilising inventions such as the printing press and the railways to mass-produce and proliferate cultural products drawn from their daily experiences in the cities.

The mythos of folk cultures were fused with the lived experiences of urban modernity to develop cultural products that were inexpensive, mass-produced and expressed as being modern. They were an exhibition of the modernity of the urban working classes.

The makers and sellers of popular culture products often belonged to the emerging middle classes, some of whom came from rural backgrounds but had “made it big” in the cities. Their products were weaved to enthrall the masses toiling in factories and living in cramped conditions.

By the mid-1940s, though, popular culture had become a melting pot of varied industries, churning out films, songs, pulp novels, tabloids and so on. In their 1944 book, ‘Dialectic of Enlightenment’ the German social scientists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer savage the “popular culture industry” as a cynical outcome of capitalist production.

They agree that the main consumers of popular culture products were the urban working and lower-middle classes, but lament that these products “confine them, body and soul.” To Adorno and Horkheimer, the popular culture industry “is not the art of the consumer but rather the projection of the will of those in control on to their victims.”

The American cultural theorist John Fiske disagrees with Adorno and Horkheimer. In his 1989 book ‘Understanding Popular Culture’, Fiske writes that popular culture was made from within and below, not imposed from above. He writes that there is always an element of popular culture that lies outside social control, which escapes or opposes hegemonic forces.

LW Levine, in his essay for the 1992 issue of The American Historical Review, writes that, to the purveyors of popular culture products, a majority of people buy into this culture of their own accord. The nature of their demand influences the creation and evolution of this culture’s products. To them it is a culture of the people, by the people.

However, in the anthology ‘Popular Culture and World Politics’, Jutta Weldes and Christina Rowley write that states and governments actively use popular culture products in many ways and for multiple purposes. Take, for instance, the relationship between popular culture and the State and governments in Pakistan.

In South Asia, popular culture — as it began to be understood from the 19th century onwards —was a by-product of the many economic and political changes introduced in the region by British colonialism. In Pakistan, right from the onset, the State began developing a monopoly over defining and designing popular culture products. This meant that these were being generated from above because folk cultures below were seen as promoting ethnic provincialism. For example, till the late 1960s, the State-owned media was not allowed to air folk songs. Popular culture products were to follow the State’s instructions to promote Pakistani society as an integrated cultural whole.

Films based on ancient folk tales (such as the 1950s Sassi) were an example of the “Urduisation” of a non-Urdu folk tale.

According to RB Qureshi in ‘Exploring Qawwali and Gramophone Culture in Pakistan’, the qawwali was not played on Radio Pakistan until the creation of the Urdu qawwali in the late 1950s. However, the line between what was being dictated from above and what was brewing below began to blur during ZA Bhutto’s populist regime (1971-77).

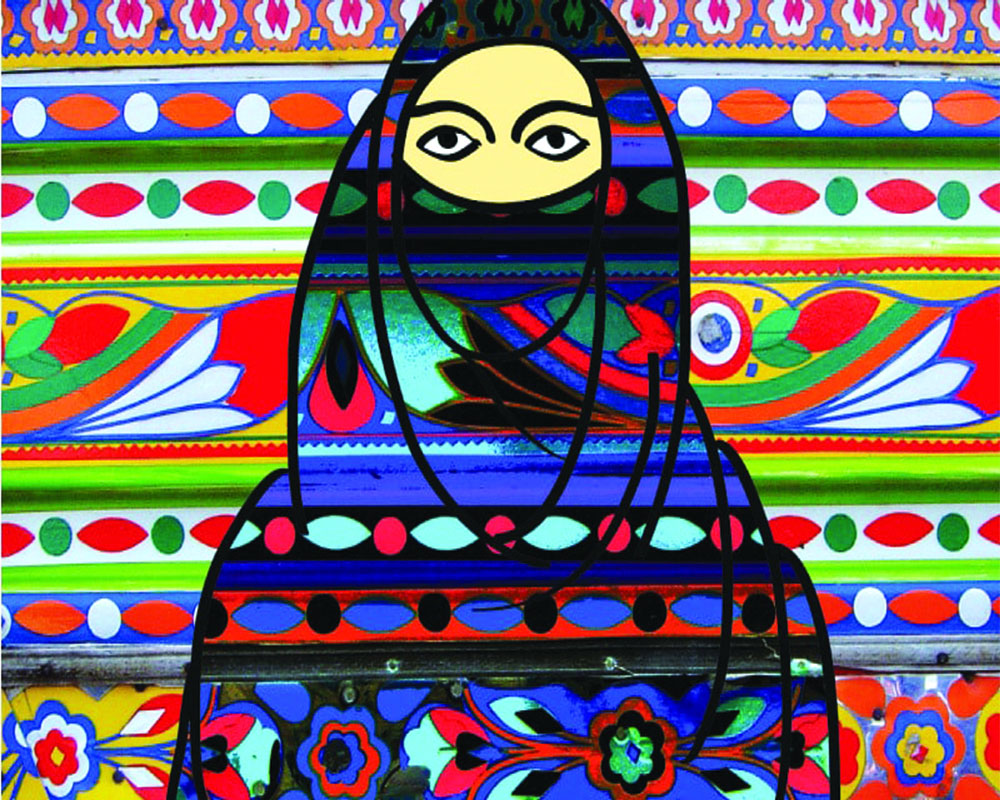

But even then, the more concentrated “regional” or Sufi themes running across folk songs and qawwalis were stripped down and presented as secularised mediations on spiritualism, which could now be enjoyed as entertainment as well. In the 1980s, the General Zia dictatorship was quick to use certain popular culture products to broadcast its ideas of Islamisation. For instance, during the dictatorship, folk and national songs became lyrical manifestations of faith, family values and the glory of State institutions (such as the military and the police). By the 1990s, the profane had become privatised and the sacred had become public. The country’s cultural spaces had shrunk or they had to add some element of the sacred to continue existing. These included spaces sponsored by multinational organisations. From the mid-2000s, popular culture in the country splintered. The popular culture products below — such as exhibitions of religiosity through unregulated sermons and speeches via digital audio mediums on the one hand, and the more secular popular culture expressions such as Umer Sharif’s stage plays employing everyday Urdu — jostled for space with the ideas of popular culture coming from the middle, such as Coke Studio, award shows and lavish TV soap operas.

What was emerging from the State above was defused and defanged. It seemed especially so when the three strata, above, middle and below, all landed on social media sites in full view of each other. I do not see their interaction in this respect as a cultural war. It is a discourse between varied popular culture products and ideas. However, it is still early to predict exactly what this might lead to.

The views expressed are personal.Courtesy: Dawn