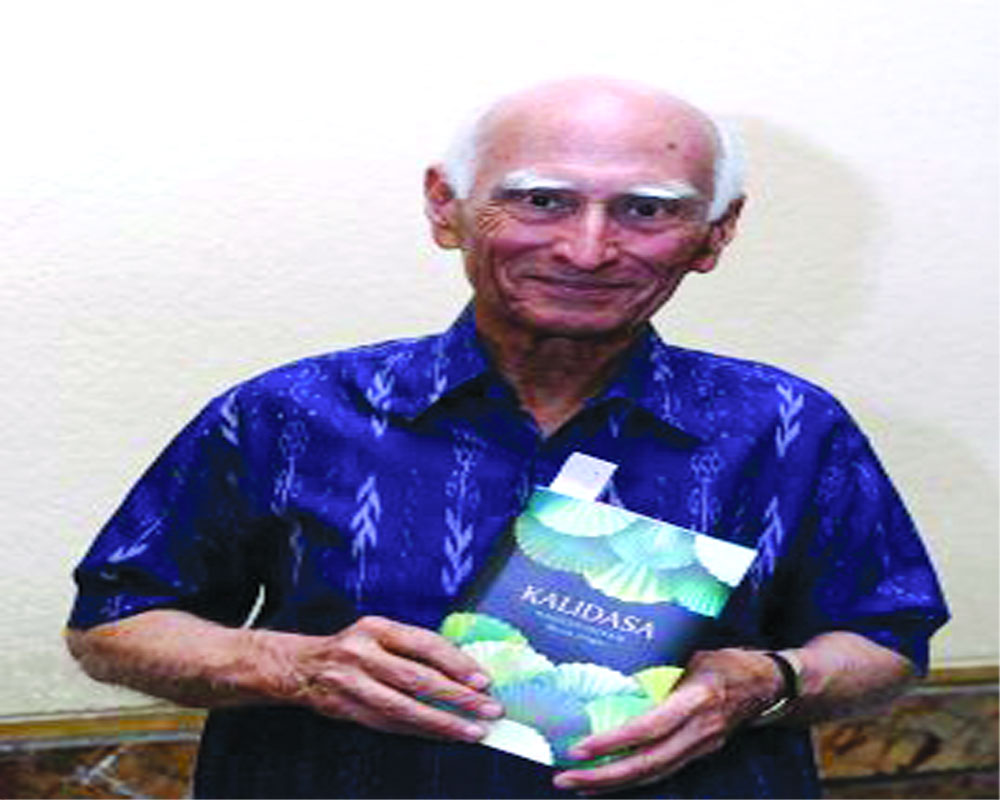

AND Haksar, a former diplomat, has become synonymous with translations of lesser-known Sanskrit texts. In conversation with Saimi Sattar about his new book Chanakya Niti, he discusses what spurs him on and how he embarked on this journey after retirement

The tones are clipped. Every syllable carefully pronounced. The accent is old school. It is during the lockdown that I connect over a phone call with Aditya Narayan Dhairyasheel Haksar, the well-known translator of Sanskrit works. Over the call, he tells me that he has found the quietest corner to sit down for the conversation so that we can proceed unhindered and undisturbed. When another phone threatens to invade the carefully cultivated mindfulness of the discussion, he pauses and shuts it out. He does not desist from making a precise point, pronouncing each word clearly while stressing upon every syllable. The attention to mindfulness and being focused seeps through even over the call and stands in stark contrast to an age where multi tasking is so glorified. While he is eager to talk about his latest translation, Chanakya Niti, but he is equally curious if I am related with another writer who shares my surname and has often reviewed his books.

During the course of the conversation, he touches on a lot of aspects, which concern his 20 translations beginning with Tales From Panchatantra in 1992, the language, which he has mastered and what makes it relevant in present times.

When it comes to Kautilya/Chanakya, Arthashastra is definitely the more talked-about text. So where did the germ of the idea to translate Chanakya Niti come from?

In the course of my translating Sanskrit classics, I have taken up all kinds of literature which I feel need public exposure. I came to the conclusion after looking at texts and their commentaries that the Arthashastra is very much in the public mind. There are books about it and people make speeches based on it too but the other work, Chanakya Niti has become a little obscured in recent years. Public knowledge and popularity of Arthashastra is based upon the discovery of manuscripts a hundred years ago in South India.

Moreover, there are in existence six main versions of Chanakya Niti. Of these, one, the Vridha Chanakya, has become better known. I thought if we are going to have a new translation it should reflect the whole corpus to give the reader a better sense of the whole corpus.

What is the appeal of Chanakya Niti in today’s day and time?

While Arthashastra is a scholarly treatise on politics, economics, diplomacy, running the government and more which is concerned with technical information directed at scholars and experts, the Chanakya Niti has verse maxims and aphorisms on life and everyday living. These are addressed to common people who are interested in knowing something about everyday worldly life namely the social, ethical and economical aspects. It is about how to get along with friends, family and others. They are addressed to individuals. As compared to other Sanskrit verses, which are embellished, these are exceedingly simple. That is why they attract common people.

Since these had become obscured over time, I felt the need to put it out in the public domain.

Is the fact that Arthashastra has often been compared to Machiavelli’s Prince the reason for its popularity?

The interesting thing is that both Arthashastra and Prince are addressed to technical expert audience. But Chanakya Niti verses are more like the advice of the kind that Socrates or Plato gave about everyday living which appeals to people. It doesn’t need deep understanding.

Is there any particular verse here that resonates with you the most?

Some verses resonate more. In fact there are two-three verses which attracted me to the whole. There is a verse that says, “Spoil him for the first five, for the next 10 discipline him, but once the son becomes 16, treat him like a friend.” This is something which was said 2,000 years ago and I think it is as relevant today as it was earlier. The other one says, “He speaks before you sweetly but spoils the word behind your back. Always discard such a friend. He is a poisoned pot with milk on top.” Both these verses are couched in such simple language and you don’t need a dictionary to understand them.

Since you’ve translated the works, what do you say to Amit Shah being called Chanakya?

The name or epigram Chanakya has from time to time been used for clever and determined political leaders and Amit Shah is not the only one. This has been going on for a long time. It has been used by every generation. But the Chanakya referred to here is more the one who wrote Arthashastra.

Your last translation, A Tale of Wonder, was a mix of cultures and religions. But in today’s times we see everything being compartmentalised separately...

In this particular case, even though it mentions Hindu gods, Chanakya Niti leaves out all considerations of organised religions as you have it. It mentions the caste system in social terms and it also points out that a person from a particular caste might be doing something else. The adjectives, religious and secular, are used very loosely these days but the Chanakya Niti is a really secular text.

The last two works which I’ve done, A Tale of Wonder and Suleiman Charitra are based upon stories derived from Arabic or Persian Middle Eastern sources. In today’s time, when everything is being compartmentalised and seen from a particular point of view, these two works depict cultural confluence and intermingling of culture.

How did you get into translating works from Sanskrit?

When I was a student, 60-70 years back in school, I had to study a classical language. My parents chose Sanskrit. My connection with the language loosened over the years. I spent 35 years as a career diplomat. When I retired I had more time at hand and thought I should get to know the language a little more. I came to a conclusion that a good way of learning a language was by translating it. So I looked at the texts which I had studied as a school boy. Over the years, it went on to include more complicated ones. The very first translation was of the Panchtantra fables that was picked up by National Book Trust more than 20 years ago. It is still in circulation. These are simple tales. I tried to concentrate on translating texts that are not in the public domain. The Tales of Wonder has been in existence for 600-700 years but it was definitely not in the public domain. No one associated Sanskrit literature with retelling the story of Yusuf and Zuleikha in terms of a parable of soul in search of God.

Did your stint as a diplomat influence the interpretation and the choice of Sanskrit?

There is one section of Sanskrit literature which is very well-known as it has been written about, translated, discussed over the last 200 years. This literature concentrates more or less on religious and philosophical texts like Gita and the Vedas. But these are only a tiny part of the vast literature that exists. There are some satires in Sanskrit about corruption in government, hypocrisy in religion and greed in business. These are facts of life and should be read.

Many of your translations have further been translated into Persian, Turkish, German, Malay, Mongolian, Newari, French, Greek, Hungarian, Polish and Russian as well as several Indian languages. What do you attribute their global appeal to?

At one stage, Sanskrit literature had spread wide from India to neighbouring regions. It was translated in other languages. In colonial times, Sanskrit literature was translated into not just English but all colonial languages. In earlier times, Chanakya Niti verses were found in Indonesia and Iran. So they do hold an appeal.

Translations can be tough as there are not enough words that can be equated with a particular one in a language? Also, the context for the verse needs to be seen in perspective of the time. Does that affect the quality of translation?

You are asking me deep questions, I am glad. There are two types of translations where the attempt is to translate from word to word and the object is to give to the person reading the translation a better idea of the exact words of which the translation is being made. That is one kind of translation. In this, very often if you read only the translation and not the original, it may not even make sense.

The other kind of translation is where you try to convey not the literal meaning but the literary meaning. In other words, you are combining both the literal and literary aspects because there is also the spirit behind it. This is the kind of translation I try to do. The difference between literary and literal is very limited in Chanakya Niti. I’ve translated two works of Kalidasa and I am also doing Vikram Urvashiyam at the moment for the Kalidasa classic series for Penguin. The language there is full of embellishment.

How do you select the text initially? Did the previous text influence it?

The first work I translated was Panchatantra as they were simpler to understand. I happened to know the editor of a newspaper and he asked me to send one every week which was published. That was encouraging as it went on for a year. Then I picked up a collection of works by the playright called Bhasha who lived 1,500-2,000 years ago. He wrote many plays, of which, some are based on stories from Mahabharata. He chose to make the villains, the heroes of his plays. These too were picked up by newspaper. Penguin had just started in India and they chose to publish it as the Shattered Thigh, which is still around. Then I got into more complicated stuff.

What kind of a schedule do you follow? How long does translating a work take?

It depends on the work you are translating from. After seeing my works getting published, I got interested and did more work. I have become a regular feature on the Penguin’s classics series. Earlier, I was sending proposals but, over time, they have been making suggestions. Kalidasa is famous as a poet and a playwright. I didn’t go anywhere near his works as I thought that would be too big. But it was the publisher that suggested that I should attempt translating the work. The first work took me a lot of time as it needed more drafting and redrafting.

How long does Chanakya Niti take?

The total verses attributed to Chanakya Niti add up to 2,000 but since that would be too much, we decided to select 300. One task was to select those and that involved a lot of reading, thinking and cross-questioning. But the actual act of translating was simple as the language is easy. While half the verses are from Vridha Chanakya, the other half from all the other five versions of Chanakya Niti. This translation gives the reader a sense of the corpus as a whole.

Children in school often do not find it an interesting language...

It seems that today, students are opting to study Sanskrit because the way it is taught and examined and the possibility of scoring high marks. Just like Mathematics. The grammar and tenses are emphasised upon. But to develop an interest in the language depends on individual temperament and also on the availability of works that could appeal to that temperament. If there were comic, erotic, heroics, colloquial works the language would have a larger appeal.

What are you planning to do next?

I am translating Kalidasa’s Vikram Urvashiyam and also, a collection of love poems which in my opinion deserves to be known better. I’ve had this text for long.