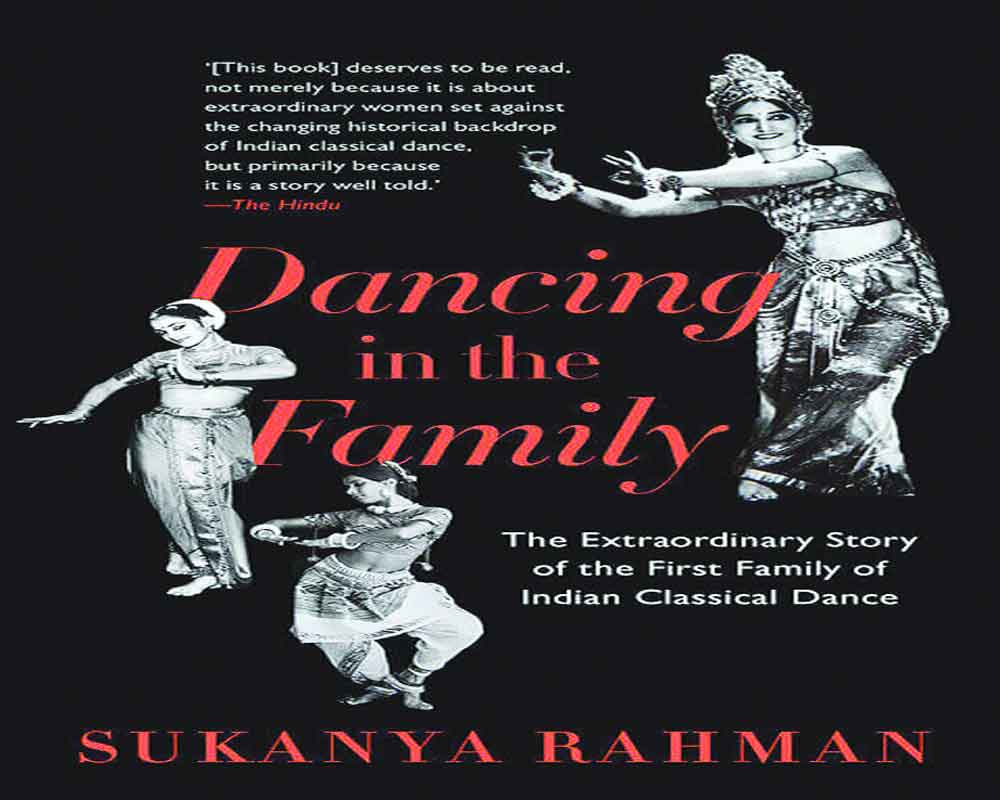

Name : Dancing in the Family

Author : Sukanya Rahman

Publisher : Speaking Tiger, Rs 499

An ode to three remarkable dancers, Sukanya Rahman’s book, is an intergenerational memoir recounted with a frank authenticity which makes for a compelling read. An excerpt:

The Bajpai apartment at 209 Sullivan Place in Brooklyn became a gathering place for Indian émigrés and their nationalist and political activities-a hotbed for the Independence Movement. Ragini was by now resigned to her husband sharing his roof and his purse with indigent political refugees from India. He was working full time for his political mentor, Lala Lajpat Rai, the nationalist leader and champion for Indian Home Rule. As councillor of the Indian Home Rule League, Bajpai had been thrust into the centre of nationalist activities. From the time it was founded in New York in 1915 by Lala Lajpat Rai, the Home Rule League had attracted the attention of British Intelligence agents operating in America. Its office at 1400 Broadway was constantly under surveillance. Radical nationalists, in an ultimate act of opposition to Britain, had sided with Germany during World War I. Several Indians, and American sympathizers of Indians, like Dr Taraknath Das, Sailendra Ghosh and Agnes Smedley, suspected of being a part of a “German-Hindu conspiracy” and a “Hindu-Bolshevik clique,” were picked up and deported or imprisoned at the jail known as the Tombs in downtown Manhattan.

Young India, a monthly journal brought out by the more moderate League, was now being used successfully to lobby Congressional support for India’s cause in Washington. Quarrels which frequently arose between more militant factions of Indian groups and institutions were usually arbitrated by Bajpai, who had a reputation for being a brilliant, fair and kind mediator.

Ragini, married to Bajpai now for almost ten years, had established herself as a respected authority on Indian dance and music. In 1928 she wrote Nritanjali, the first book on Indian dance to be published in English. Based on her studies of The Mirror of Gesture by Ananda Coomaraswamy, some translations from the Natya Shastra and her own dances, this small book simply and eloquently sought to unravel the spiritual complexities and intricacies of the classical Indian dance vocabulary for the uninitiated. Critical acclaim of the book had made a name for her both in America and in India.

She believed dance and music, one of the finest phases of Hindu life, must not be allowed to remain unknown to the world. “The world should know of it, and the great masters should ponder over the possibility of its revival and renovation for the whole world… Some people who love Hindu music and dancing must give their lives to it. I love India and I am trying to find the beauty of my life through Hindu music and dancing to which I have consecrated my life.”

She came to understand that Indian dance was an act of worship and not for entertainment. “Sadly enough, to us the phrase Oriental dancing has pretty generally brought up little else than the picture of the ‘danse du ventre’ which was for many years the particularly spicy feature of every carnival or fair from Maine to California,” wrote John Martin, dance critic of The New York Times; “…it is, therefore, a happy circumstance that there should be a few devotees like Ragini who are able not only to perform the classic dances but also to write about them in such a form that we of the West may acquire some appreciation of them before they disappear from the earth.”

And The Dancing Times, London, wrote: “It is difficult to study dancing of all arts, from a book: yet expert guidance, accurate description, and careful explanations… are offered in this valuable volume by Sri Ragini. It carries its own commendation upon every page being the work of an artist for artists.”

Ragini was now sought after among both wide and select circles of the public for her lively, illuminating programmes of Indian dance and music. Audiences responded enthusiastically to her interpretations of ancient and modern dances of India’s gods and goddesses. With structured rhythmic development, graceful hand gestures and facial expressions, she communicated to audiences the charm and vivacity of the divine flute player, Krishna, and his beloved, Radha.

She toured the country with two colourfully costumed North Indian musicians who accompanied her dances. In 1928 she booked this “Trio Ragini” into the Booth Theatre on Broadway for a series of performances which sold out. The New York Times described the performance as “an exotic evening of East Indian Music at the Booth Theatre last night, marked by half lights of subtle atmospheric suggestion and by highlights of appealing lyric beauty-the songs and dances of Ragini won her audience with simple truth of graceful interpretation rare to be seen in the theatre. Several of Ragini’s numbers had to be repeated, beautiful plastic poses accompanied by sinuous serpentine movements of the arms and hands.”

Her husband, meanwhile, had given up a lucrative job with a pharmaceutical company in order to devote his time to Lala Lajpat Rai and the freedom movement, often travelling across the country to raise funds for the cause. For Ragini this led to a variety of experiences since she was constantly devising ways to augment her income. She appeared in Carnegie Hall in a prologue to The Light of Asia, Himangshu Roy and Devika Rani’s film based on Edwin Arnold’s poem on the life of Buddha. The film received a lukewarm reception, but Ragini’s brief song and devotional dance, invoking Shiva, created a stir. “Sri Ragini is a native of India,” wrote one American critic, “she is as naturally imbued with the traditions of her country as any other artist who ever entered this country… Ragini Devi has a truly beautiful voice, a mysterious manner of intoning her songs, and with a sensuous style of dance to add to the atmosphere.”

Dancing in the Family written by Sukanya Rahman is published by Speaking Tiger