With the certainty that the Taliban will return to the corridors of power in some form or the other, it is a no-brainer to conclude that New Delhi needs dexterity than ever before

In 2001, General Abdul Rashid Dostum, then a fierce warlord, the first Vice President of Afghanistan and a key political figure for the northern Afghan provinces now, apparently said the following to the Captain of the US Army Special Forces ODA 595 fighting the Afghanistan war. The latter was on a classified mission in the wake of the September 11 attacks that led to the fight for Mazar-i-Sharif. “There are no right choices here. This is Afghanistan. Graveyard of many empires. Today you are our friend, tomorrow you are our enemy…You will be cowards if you leave. And you will be our enemies if you stay.”

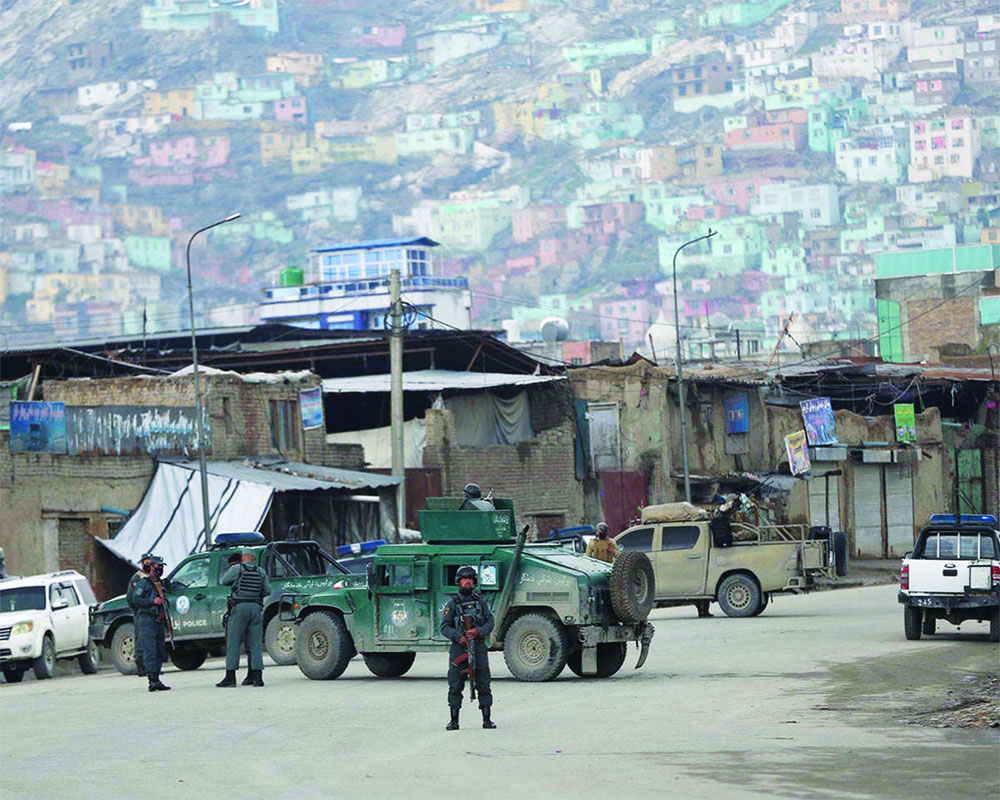

With close to 100 attacks in Afghanistan post the signing of the US-Taliban deal, the decree by Afghan President Ashraf Ghani to release 1,500 Taliban fighters and competing power axes in the country with Opposition leader Abdullah Abdullah and Ghani holding parallel inaugurals of the new Government in Kabul, Afghanistan threatens to come full circle from its Taliban-ruled days. Indeed, 18 years later, the US is caught between the coward-enemy binary, with the Taliban spokesman Za-bihullah Mujahid announcing, “As per the US-Taliban agreement, our mujahideen will not attack foreign forces but our operations will continue against the Kabul administration forces.” Moreover, as the Trump administration has deliberately concealed two written annexes of the deal from the public, much remains in the realm of speculation regarding the details of the pact. This would lead one to make assessments, whether or not the Taliban is living up to the end of the bargain, which is almost impossible.

The US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s latest dash to Kabul to reconcile warring parties in Afghanistan, to form a unity Government and begin intra-Afghanistan talks, did not see any progress. However, the Trump administration’s threat of slashing $1 billion in assistance to Afghanistan has yielded some result with the Ghani Government and the Taliban agreeing to prisoner-swap, starting March 31. There has been little progress on the issue of two parallel Governments in Kabul. As the US is dealing with one of the worst pandemics in its history right now, its resolve to leave Afghanistan in the next 14 months is going to further strengthen. To this end, there are a few questions that need clear answers from India’s point of view. What does the emerging situation mean for peace in Afghanistan and the larger regional stability in the region? How will the resultant geopolitical and geostrategic space in Afghanistan be used by external powers? What should be India’s role in a new Afghanistan, where the Taliban has gained renewed legitimacy?

Depicting a change from its earlier stance, New Delhi welcomed the pact between the US and the Taliban. During his first foreign trip, Indian Foreign Secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla reached Kabul for a two-day visit and met top Afghan political leaders a day before the US-Taliban peace agreement was signed in Qatar on February 29. The Indian Ambassador to Qatar, P Kumaran, was also an invitee of the Qatari Government to the signing ceremony.

In November 2018, two Indian representatives participated, non-officially, in the Moscow chapter of the Afghan peace talks, which included a high-level representation from the Taliban. Besides the fact that it doesn’t want to be in a camp opposite to the US, an increasingly close partner of India in global endeavours, there is an apprehension in New Delhi about being left out of the processes that are shaping Afghanistan’s politics if the latter continues strategic distancing from the Taliban.

Pakistan’s role as one of the facilitators in bringing the Taliban to the negotiating table has further shrunk New Delhi’s diplomatic heft, apropos Afghanistan at the global high table. As such, there are signs of greater skin in the game in Afghanistan for India to pre-emptively deal with an emerging politico-strategic dynamic over there.

Afghanistan has come full circle — first the ouster of the Taliban Government, then a democratic Afghan Government with security force, to the return of the Taliban as a legitimate political player. Despite the Americans calling it an agreement “between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, which is not recognised by the US,” there is no denying the fact that the peace deal has brought a sense of legitimacy to the Taliban. This compels a shift in New Delhi’s Afghan strategy.

There are at least three factors that point to India’s shifting policies in Afghanistan, albeit without an endgame. First, India’s improved relations with the US and its increasing convergences with Washington have left little room for it to be on a side that’s vehemently opposed to the latter. More so when China is becoming a key player in Afghanistan. US President Donald Trump, during his recent visit to India, is said to have solicited support from New Delhi for the Taliban deal. Second, America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan tacitly thrusts a greater regional responsibility on India. This is not just in correspondence to the emerging regional expectations on the part of Afghanistan but also a palpable realisation in its scheme of regional leadership. Finally, having a greater skin in the game for India in Afghanistan, albeit with deliberate moderations in its role over there, seems to be the best option for New Delhi as the choice is between being there and being left out.

India’s role in Afghanistan since 2001 has largely been focussed on the civilian reconstruction of the war-torn country, with involvement in the security sector limited to training Afghan officers in Indian military institutions, and a rather restrained willingness to supply military platforms and equipment. Owing to recent developments, questions over the nature of India’s role in Afghanistan are being acutely debated in the Indian strategic community.

The Ghani-led Afghan Government in Kabul has barely emerged from a divided election result and is faced with an uphill task in terms of thrashing out the future of the country with the Taliban, which has steadfastly refused to recognise its legitimacy, calling it a puppet of the US Government. Much is also contingent on the release of the remaining 3,500 Taliban fighters as promised by the Ghani Government. Therefore, while New Delhi, Washington and Kabul may still call for an Afghan-owned and Afghan-led peace process, it will be naïve not to consider the return of a full-fledged violence by the Taliban.

For India, the most pertinent question is: What kind of leverage has Pakistan gained in the entire gamble, in exchange for its role in the US-Taliban talks, given its influence over the Taliban leadership and intentions to maintain strategic depth in that country? Pakistan’s regaining of the “strategic depth” runs counter to all efforts to establish an influential Indian presence in Afghanistan.

The recent heinous attack at a gurudwara in Kabul that killed 28 Sikhs portrays the complexity of the challenge for India in Afghanistan as the only legitimate backer of the elected Afghan Government even as the US purposefully recedes. If India continues to guard its stakes, irrespective of the nature of the next Government over there, it should brace for a long resistance and fight with the Pakistani deep state. As was evident in the gurudwara attack, Pakistan will intensify the use of the Haqqani network and other terrorist factions that it has a leverage on, as a front to attack India.

The India-Afghanistan strategic partnership, among other things, is based on a resolute Afghan Government in Kabul. At this juncture, with the certainty that the Taliban will return to the corridors of power in some form or the other, it is a no-brainer to conclude that New Delhi needs dexterity than ever before. Add to this, the complex picture of China, which has shown its willingness to invest in Afghanistan. The US pullout, therefore, can be an opportunity for India to fill the strategic gap. But to do this effectively, it would either require an enhanced security apparatus in Kabul, whether by partnering with another country or by itself. Both will have tremendous and long-drawn repercussions.

(Vivek Mishra is deputy director, KIIPS, Bhubaneswar, and research fellow, ICWA, New Delhi. Monish Tourangbam is assistant professor Manipal University, Karnataka)