Ambedkar’s essence lies in heralding a systemic change, instead of craving for political freedom... India’s Dalit community should not look forward to the reincarnation of Ambedkar, but in due course of time, each member of it must transform himself/herself to an Ambedkar.

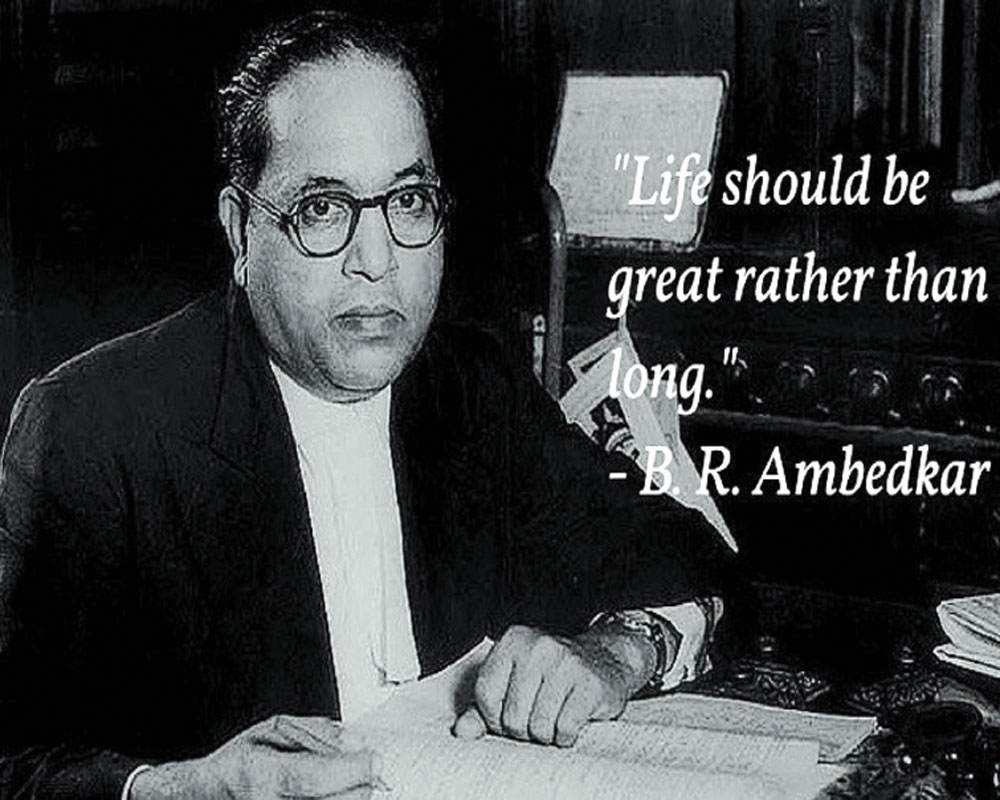

While commemorating the 128th birth anniversary of Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar today, one can certainly proclaim that he was no less a prophet who lived, inspired and left a legacy for millions on this planet. The best part of his life and times, unlike any other leaders, is that he continues to remain broadly relevant at the heart of not only the Dalit community, but also among those who struggle to live a dignified life in society.

What Ambedkar had fought for is a set of entrenched social differences, discriminations, inequalities in socio-religious traditions of Hinduism. Sad part of casteism is that it is being practiced for generations without any compunction. And, hence the patterns and various modes of this age old system are reproduced again and again, simply to continue it for depriving a large section of society.

The very essence of Ambedkar lies in the fact that throughout his political philosophy, social preceded the political elements. He was neither a staunch individualist philosopher like many that we experience in the Western political tradition, nor a conservative communitarian.

While discussing various aspects of Ambedkar’s philosophy, it would remain incomplete if we don’t bring out his interaction with Mahatma Gandhi. Arrival of Ambedkar to India’s freedom struggle against the British Raj itself is quite significant. He tried to articulate an alternative political ideology by challenging the core credentials of the existing nationalist movement then solely spearheaded by Gandhi. On several occasions, he argued with Gandhi to put an end to the scourge of “untouchability” before India receives freedom from the British colonial yoke. When Gandhi’s prime strategy of the liberation movement was aimed at “British leaving India”, Ambedkar thought he was simply doing lip service by launching various programmes to eliminate untouchability instead of addressing the root causes of an issue that is deeply embedded to Hinduism. Therefore, for Ambedkar, Gandhi’s loyalty to Hinduism was an hindrance to eradication of untouchability.

Further, Ambedkar also criticised Gandhi for eulogising the Indian villages as illustrative of unique units of social, economic and political equilibrium. He advocated that “Indian villages represent a kind of colonialism of the Hindus designed to exploit the untouchables. The untouchables have no rights. They are there only to wait, serve and submit. They are there to do or die. They have no rights because they are outside the village republic and because they are outside the so-called republic, they are outside the Hindu fold. This is a vicious circle. But this is a fact, which cannot be gainsaid.”

Thus, Ambedkar rebuffed Gandhi on the idea of the village republic as this is the place where Dalits encounter extreme levels of exploitation in the form of master-servant relationship laced with pollution and purity.

Ambedkar’s anguish was that Gandhi could have certainly resolved the issue of untouchability, but he did not. The two of the most important non-violent historic weapons that Gandhi used against the British were Satyagraha and fasting. And to his credit, he had conducted altogether 21 fasts throughout the course of India’s struggle for Independence. But Ambedkar retorted that “In these 21 fasts, there is not one undertaken for the removal of untouchability.” He also observed, “But Mr Gandhi has never used the weapon of Satyagraha against the Hindus to get them to throw open wells and temples to the untouchables.”

Therefore, he most eloquently put it that “The Hindu society insists on segregation of the untouchables…It is not a case of social separation, a mere stoppage of social intercourse for a temporary period. It is a case of territorial segregation.”

This all forced Ambedkar to demand a separate electorate for the untouchables in the lines of Muslims, which was conceded by the Indian National Congress. He defended such an electorate for the untouchables by highlighting that since voting was severely restricted by property and educational qualifications, the geographically highly disparate depressed classes were unlikely to have any influence in the decision-making process. It indicates that for Ambedkar the untouchables were completely outside the fold of the Hindu society. Hence their political representation should only be done in the mode of separate electorate both for the Central and Provincial Legislatures.

However, Gandhi declined to accept separate electorate for the untouchables as he believed it to be an integral part of Hindus. That is why he was ready to give them reserved seats in general constituencies. Meanwhile when the British Government endorsed Ambedkar’s separate electorate proposal in the historic Communal Award of 1932, Gandhi went on to fast inside the Yervada jail in Poona. Finally, the historic Poona Pact was signed between Gandhi and Ambedkar, according to which the latter had to accept the reservation of seats for Dalits within the caste-Hindu electoral constituencies.

His famous book, “Annihilation of Caste” published in 1936, Ambedkar started a public debate by asking why the upper-caste Hindus tend to treat their fellow beings with aversion and prevent them from taking part in public activities along with them. For him, “The real enemy is not the people who observe caste, but the Shastras that teach them this religion of caste.”

With serious differences with Gandhi, and his general aversions towards Hinduism, Ambedkar publicly converted himself to Buddhism on October 14, 1956, at Deekshabhoomi, Nagpur. This spearheaded a new Dalit Buddhist movement across India in later years.

Today politics is all about caste, race, religion, polarisation and mudslinging. Political narratives are crystallised in and around larger identities based on these very lines. Ideology has taken a back seat in political discourses. Parliament is merely used to propagate narrow party goals and hurling insulting words at political rivals. Leaders hardly deliver speeches; neither are they engaged in peaceful, respectful and meaningful dialogues. They are all in a continuous race to stay in the power corridors so as to safeguard their power, prestige and property of course for now and future.

At such a critical juncture, political leaders of all hues must be inspired by what Ambedkar practiced and how he amalgamated various sources to leave behind the world’s largest written Constitution to us. In fact, he did this Herculean task in almost three years of rigorous debate, discussion and dialogue in the historic Constituent Assembly of British India.

Ambedkar will certainly be revered as the “Renaissance Man” of Indian political thought who had fearlessly spoken out for the downtrodden and had helped them set forth their arduous journey only and only for liberty, equality, and dignity. He is truly a “polymath” in the same sense, when the concept was enunciated first by German philosopher Von Wowern in the year 1603: “It is the knowledge of various matters, drawn from all kinds of studies…ranging freely through all the fields of the disciplines, as far as the human mind, with unwearied industry, is able to pursue them.”

Ambedkar, like many other Dalit activists and philosophers, had just started the long journey of reclaiming equality in largely caste-divided Indian society. Surprisingly, it is a myth why caste system in this country remains endured even after years of anti-caste movements, social awareness campaigns and reformist struggles and lastly prohibition of untouchability by the Constitution of this country. Caste survives despite globalisation, scientific development and mass political mobilisation of the Dalits.

Needless to say that caste system against which Ambedkar fought throughout his life is a contested terrain.

What he tried to preach and profess in India was no other than his great learning lessons from his professors back in Columbia University in the US. He was mostly influenced by John Dewey, Edwin Seligman, James Harvey Robinson and Alexander Goldenweiser. What flowed from his work in political life indicated that his philosophical narratives had a serious impact of Dewey and the progressivist and modernist Zeitgeist that prevailed in America during those days. Many say that Dewey could even be regarded as a “Guru” of Ambedkar, if at all he had one.

India’s Dalit community should not look forward to the reincarnation of Ambedkar, but in due course of time, each member of it must transform himself/herself to an Ambedkar so as to put an end to the evils of the existing caste system. Untouchability must go in entirety. The din and noise sounded by many of the helpless Dalits who still undergo subjugation, humiliation, mental and physical torture should be over by now. What needs to be underlined here is that Dalits must be economically empowered to fight out what comes on their way in daily life. Mere political representation and a reservation system used by few Dalits would neither uplift the whole community nor this could support them struggling against the regular curse of untouchability.

Lastly, Ambedkar’s essence lies in heralding a systemic change, instead of craving for political freedom. To bring this in and practice his philosophy in true sense of the term, along with massive socio-political awareness, economic strength of the Dalit community must be enhanced. Unless they move in this direction, they will be struggling in the same old and humiliating graded system, constructed and reconstructed over the ages, despite the world being “Flat” for the rest of the humanity. Instead of arguing for radical change in the Indian social system, a “piecemeal engineering” can be much better in finding a way to achieve “social engineering” for the Dalits and their brethren in the days to come. The annihilation of the caste may take longer, but nimble steps towards the same can start from right now.

(The writer is an expert on international affairs)