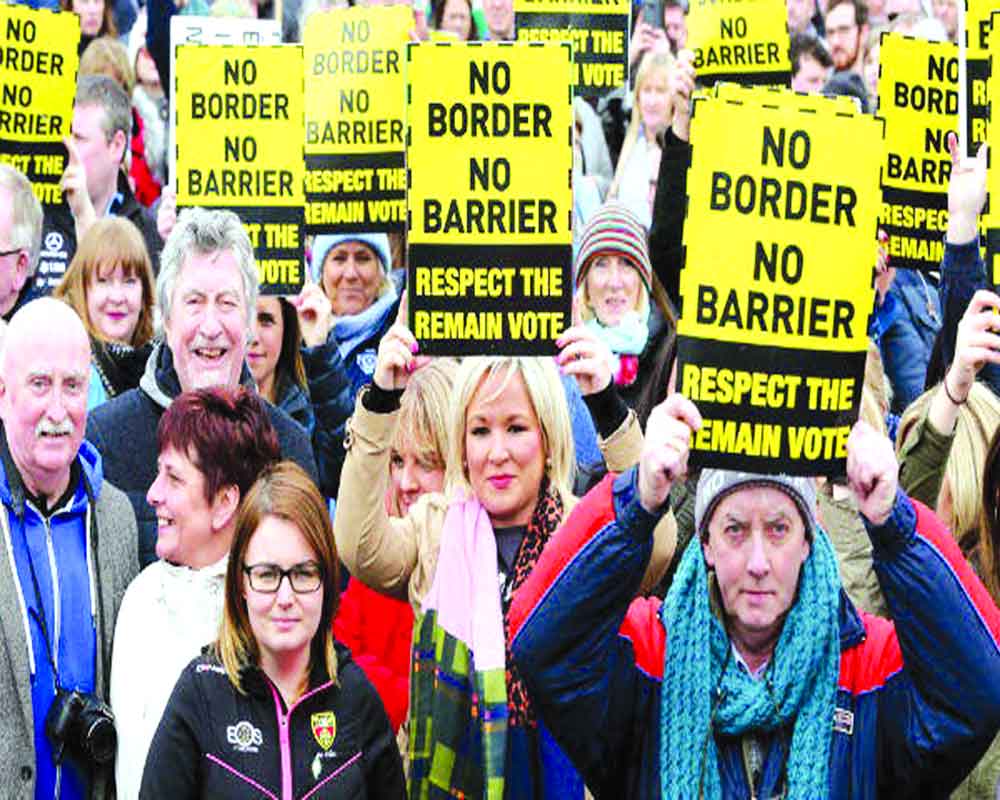

What haunts Northern Ireland at the moment is none other than Brexit, which is gradually opening up the old wounds of the historic Good Friday Agreement. The very idea of Brexit has destabilised politics by forcing people to take sides between Britain and Ireland

The exit of Britain from the EU would weaken the bloc. The UK being one of the wealthiest and influential nations, its departure might impair the cohesiveness and effectiveness of the EU. Further, it may trigger more such exit demands from some other members, delivering a potential threat to the survival of the EU. International Monetary Fund (IMF) has already warned about the economic impact of Brexit — reducing trade, investment and economic growth — on the entire the EU region. It would make the mega investors nervous and could spark a sharp drop in the stock markets and volatile swings in the currency exchange rates across the continent.

Since June 23, 2016, when the final Brexit vote took place and the majority of the Britishers took a hard decision to leave the EU, the sign of elation has already died down in the polity, economy and society of Britain. Since then two Prime Ministers — David Cameron and Theresa May — had to resign for not being able to manage either the post-Brexit political crisis or the complex negotiations with the EU. Today Britain is at a crossroads and the EU is divided.

What makes the Brexit process more complicated is Britain’s relationship with Northern Island. Currently, the UK is a part of the EU’s customs union and the single market. The problem is that if Brexit at all happens, it will have to leave both the market and the bloc. Once this happens, the status of the UK-Northern Ireland border will turn into a customs border, coming along with traditional checks and controls. This will entail entirely a new system, full of restrictions and creating new problems for both the traders and the common people. In addition to practical and business hurdles, what concerns the people of Northern Ireland most is the new psychological and political situation that might emerge out of the Brexit. In December 2017, in a European Council meeting, the UK and the EU adopted a joint report, wherein the former pledged to avoid a hard border. But the most unfortunate part of this process is that Cameron and May could not map out a plan to resolve the Northern Ireland border issue. As the Brexit confusion mounted, the EU insisted on adding a “backstop” provision to the withdrawal agreement. This simply means that if the UK can’t offer any alternative arrangements, then this backstop idea indicates that Northern Ireland will continue to remain in the EU customs union and full regulatory alignment with the single market, mainly for goods. This essentially eliminates all the upcoming checks and controls heralded by a new post-Brexit scenario.

The British Government’s stated claims, such as leaving the EU’s customs union, single market, preventing a hard border with Northern Ireland and ensuring a countrywide approach to Brexit, seem completely unimaginable by the new administration of Boris Johnson. He is running out of time, ideas and political commitment in this high stakes stand-off.

Brexit has potential to affect the historic Good Friday Agreement or Belfast Agreement signed on April 10, 1998, between the UK and the Irish Government and most of the political parties in Northern Ireland on how Northern Ireland should be governed. It made it clear to the international community that Northern Ireland will remain part of the UK unless there is consent of the majority of the people in this part of the island. Thereafter, the creation of an assembly with a power-sharing executive largely ensured the representation of both the warring communities — the Protestants and the Catholics — in policy making. Again the EU membership of both Ireland and the UK made this fragile peace more viable by enabling quick communications and by reducing physical, psychological and most importantly, economic barriers for the benefit of this small island. However, the sad part of the Belfast Agreement is that it has not been able to bring forth a durable solution to the most intractable constitutional questions looming large over the Northern Irelanders.

What haunts Northern Ireland at the moment is none other than Brexit, which is gradually opening up the old wounds of the historic Good Friday Agreement. The very idea of Brexit has destabilised politics by forcing people to take sides between Britain and Ireland. At least for more than two decades of the Agreement, people who fought for establishing their religious identities were able to take a break from their identity politics of the past: the Unionists remained part of the UK and felt reassured that the province’s future could only be changed through an open poll whereas the Nationalists Irish had a greater say in local affairs. But today, the inconclusive and the most confusing Brexit process has reignited the old passions and caused polarisation along the Orange (Unionists) and the Green (Nationalists).

Finally, what brings home utter chaos is all but the policy decisions and political uncertainty of the Johnson Government. It is making peace more fragile in Northern Ireland. At the core of the famously unwritten Constitution of the UK is the principle that the PM is there in office as long as he enjoys the confidence of the House of Commons. It’s not clear at all whether Johnson has that crucial support. And this is wreaking havoc for Northern Ireland.

(The writer is an expert on international affairs)